June 22, 2018

Source/F. Hartung, A. Jamrozik, G. Aguirre, M. Rosen, D. Sarwer, A. Chatterjee.

Source/F. Hartung, A. Jamrozik, G. Aguirre, M. Rosen, D. Sarwer, A. Chatterjee.

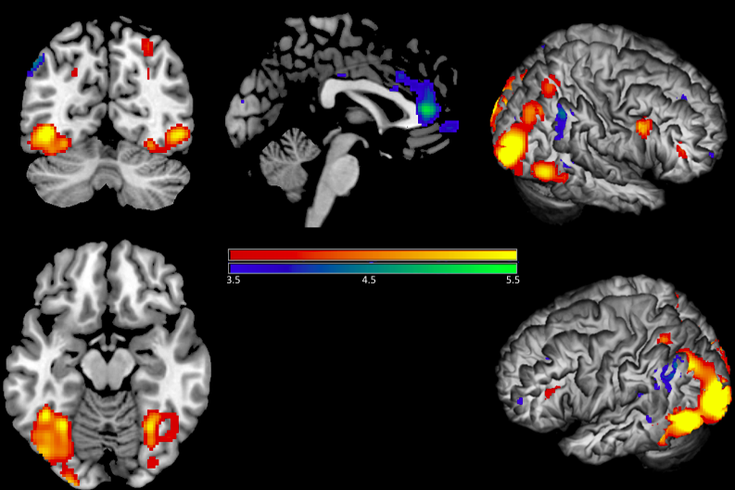

These brains scans show what happens when people view people with facial disfigurements. The red and yellow portions show increased activations in visual cortices while the blue and green portions reveal decreased activations in areas of the brain that are associated with empathy.

People tend to place individuals with facial deformities in a negative light – and they may not even realize it.

Researchers at Penn Medicine's new neuroaesthetics research center – the first in the United States – have been studying the ways people react to those with facial disfigurements.

"Other people tend to regard people with relatively minor facial disfigurements as having all sorts of negative attributes," said Dr. Anjan Chatterjee, who is heading the research center. "They're less honest, less competent, less hard-working and so on."

Using the implicit information test, which has revealed implicit gender and racial biases, Chatterjee said researchers discover that people aren't aware they hold such biases toward people with facial deformities.

Further research shows that the brain's frontal cortex deactivates when people view facial deformities Chatterjee said. The frontal cortex is considered part of the brain's empathy network and tends to be active when someone feels compassion for others.

When the frontal cortex deactivates, it leads to stigmatizations.

That's just a bit of the research that will take place within the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, which was formally announced on Wednesday. The research center will bring together a team of experts in neuroscience, psychology, business, architecture and the arts.

"It's a little bit like fish swimming in water, not being aware of the water. We are embedded by the aesthetic world all of the time and our choices are being made by this." – Dr. Anjan Chatterjee

Other research is examining people's psychological reactions to interior architectural designs and investigating how people with neurological diseases view different forms of art.

Chatterjee, who chairs the neurology department at Pennsylvania Hospital, hopes to build the research center into an international hub for neuroaesthetics, a burgeoning field that studies the biological way aesthetics influence the decisions people and communities make.

"How many of your decisions and choices were based on aesthetic criteria?" Chatterjee asked. "When you get up and decide what shirt or blouse you're going to wear – that's an aesthetic choice. Just in your bedroom, the color of your walls or what may be hanging on your walls is an aesthetic choice."

Anjan Chatterjee

It is believed, though not proven, that communities also base decisions on aesthetics, Chatterjee said.

"It's a little bit like fish swimming in water, not being aware of the water," Chatterjee said. "We are embedded by the aesthetic world all of the time and our choices are being made by this. It's so embedded that we don't sit back and say, 'What's going on? Why is this?'"

Now, Chatterjee and a team of researchers are asking such questions. And he sees the research center as an opportunity for the University of Pennsylvania – and Philadelphia – to take the lead in a new field.

There is a similar neuroscience research center in Germany that studies empirical aesthetics, such as music and literature, Chatterjee said. But the Penn center will be the first to examine visual neuroaesthetics.

Researchers across Penn's network will examine how neural systems impact aesthetic choices, primarily focusing on three major elements – basic science, translational science and communication.

"It's fertile ground to try to bring people together and mount a coordinated way of trying to look at these sets of questions, which I believe are really fundamental to what it means to be human and to flourish as a human," he said.

Source/Penn Medicine

Source/Penn Medicine