April 06, 2020

Courtesy/Penn Medicine

Courtesy/Penn Medicine

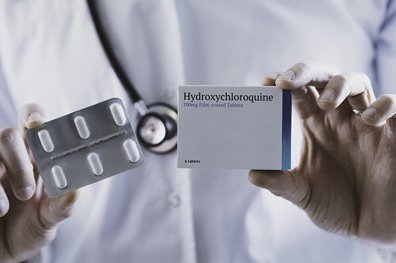

Penn Medicine researchers are enrolling patients in a trial examining hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug, as a potential treatment for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Penn Medicine is leading a new clinical trial evaluating hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug hyped as a possible treatment for COVID-19, the infection caused by the coronavirus.

Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine are enrolling patients into the study, which will examine the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Hydroxychloroquine, which also can treat lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, is among various drugs that scientists say may prove effective at treating COVID-19. President Donald Trump particularly has pushed it, noting the federal government has stockpiled 29 million pills. But much remains unknown about its potential.

Initial research has produced mix results. In one study, the medication showed no significant benefit. In another, HCQ appeared to improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients, but the study's small sample size and methodology have been criticized.

"We know HCQ can be an effective anti-viral in a lab setting, but despite recent public conversation, there is no definitive evidence it can work in humans infected with COVID-19," said Dr. Ravi K. Amaravadi, principal investigator of the Penn trial and an associate professor of hematology-oncology. "It is our hope that this trial will provide critical evidence in combating the current pandemic."

The study, dubbed "Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 with HCQ (PATCH)," includes three separate sub-studies.

The first will compare HCG to a placebo in COVID-19 patients quarantined at home. The second will focus on the different outcomes associated with high and low doses of the drug among hospitalized patients. The third will gauge the drug's effectiveness as a prophylactic for health care workers who are treating COVID-19 patients.

"The need for the third sub-study here is critical, as we try to keep the people working on the front lines of this pandemic healthy so they can continue to keep the nation's health care infrastructure up and running," said Dr. Benjamin Abella, an emergency medicine professor at Penn.

The primary objective of the first sub-study is to determine whether the drug reduces the number of days patients must be quarantined. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, patients must be fever-free for 72 hours and see an improvement in symptoms before ending their isolation. They also must wait at least 7 days since their symptoms started.

The goal of the second sub-study is to reduce the discharge time for hospitalized COVID-19 patients and to calculate the correct dose of HCQ.

The first and third sub-studies are double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, which means that neither the patient nor doctor know whether they are assigned to the intervention or placebo group. If a patient starts to feel worse, they can be "unblinded" and given the drug if they were in the placebo group.

Researchers have gotten the trial up and running in less than a month, working quickly with partners on securing funding and arranging for the drug and placebo. The HCQ for the study won't come from existing supplies. Instead it will be provided through an agreement with Sandoz, a division of Novartis, according to WHYY.

"This is an unprecedented time, and it will take unprecedented cooperation, resources, and leadership to get through it," added Dr. J. Larry Jameson, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine. "This trial shows Penn's ability to step up to meet that responsibility and investigate the scientific questions the world desperately needs to answer."

Last month, Penn Medicine launched its Center of Research for Coronaviruses and Other Emerging Pathogens, which aims to centralize coronavirus research efforts and boost collaboration between scientists and clinicians.