July 20, 2015

@JawshKruger, @SeptaRamblings, @JoeSepta, SeptaBlog.com/Twitter

@JawshKruger, @SeptaRamblings, @JoeSepta, SeptaBlog.com/Twitter

SEPTA riders take advantage of the electrical outlets on the Market-Frankford line and Silverliner cars.

Since 90 percent of American adults own cellphones and misery loves company, it is nice to know that 90 percent of American adults have also felt the keen sting of a "low battery" warning. When that little red symbol of death begins to glow and there is no electrical outlet in sight, the next device-less minutes (or, in a nightmare scenario, hours) begin to flash before our eyes.

What if I need to make an emergency call? What if I get bored? What if I can't open Google to prove to my best friend once and for all that it was Bryce Dallas Howard in "Jurassic World" and not Jessica Chastain?

For many, panic sets in, whether the threat of needing to use a device is real (being in a true emergency) or imagined (not being able to answer client emails quickly enough). After all, mobile devices, and especially smartphones, have become inextricably linked to their users' daily lives.

Move over, "manspreading" -- it appears plugging in in public is the next big etiquette blunder.

In fact, a recent University of Missouri study found that iPhone users experience a "lessening of 'self'" when separated from their devices. That same study found that physical separation from devices made iPhone users' heart rates, blood pressure levels and anxiety increase. A recent Gallup poll also found that 52 percent of smartphone users check their devices a few times an hour or more. There's even a word for the fear of losing access to your smartphone: Nomophobia, or "no-mobile-phone-phobia."

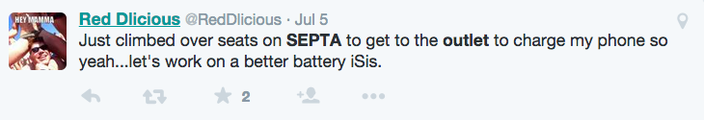

And thus mobile device users have been driven to extremes. They squat next to awkwardly placed wall outlets, huddle together over a rare airport power strip or, in perhaps the oddest case, wait eagerly for their fellow SEPTA Market-Frankford Line rider to vacate the only seat on each car with a maintenance outlet. Sometimes, they'll just plug in from across the aisle, instructing other riders to step over their power cord. Move over, "manspreading" -- it appears plugging in in public is the next big etiquette blunder.

Some cities are taking action against outlet hogs. Late last year three Los Angeles Metro riders were arrested for stealing electricity, as was a London man riding the Overground just this month. Both cases seem to be run-ins with quota-hunting cops, but they bring up an interesting point: City governments are perfectly within their right to stop the public from using their maintenance outlets to juice up.

Luckily, SEPTA has no interest in cuffing anyone looking for a charge, SEPTA representative Jerri Williams said, though she does urge customers to use caution.

"Although we do not stop anyone from using them, we don’t encourage people to. Those, of course, are not for charging your phones, and if there was some sort of electrical surge, there’s a chance you could short out your phone."

"SEPTA discourages the use of these outlets for charging phones and other electronic devices. The purpose of these receptacles is to power up diagnostic tools while the train car is at rest and has a known steady voltage source. Our diagnostic tools typically have surge and over volt protection internally in the equipment. Additionally having charging cords on the floor creates a tripping hazard and if these charging cords are on floor in rainy or snowy weather they are not GFI protected."

Of course, plugging into a public outlet when you need to call for a ride or check in with family about a delayed flight makes perfect sense. Topping up a battery on a four-stop subway ride seems a bit stranger, and frankly unnecessary, hence the annoyance it causes. There could be many reasons, though, why a rider would want to get a little extra juice underground. For instance, 25 percent of smartphone users occasionally use their devices to find public transit information, and frequently charging your phone battery is actually healthy for it.

More significantly, 10 percent of Americans own a smartphone but don't have Internet access at home, and 15 percent have limited options for Internet access other than their phones. The 7 percent of the population where these qualifiers overlap is considered "smartphone dependent." This group is more likely to have low household incomes and levels of educational attainment and less likely to have a bank account or be covered by health insurance. In other words, who knows, maybe the MFL outlet hogs plug in because they're heavily dependent on the electricity, their phone, or both.

So while public outlet use may be just another annoyance on your morning commute, it's clear that there is a real need for more ways to charge up. As the Internet becomes more commonly considered a public utility and more of us rely on mobile devices, it's time for cities to step up and make access to our connected devices easier.

With the right advertisers on board there's no reason charging stations -- and maybe even Wi-Fi hotspots, if we're getting greedy -- couldn't pop up on street corners like pay phones once did.

As usual, the private sector has caught on to this need way faster. Plenty of companies like New York-based Brightbox are pedaling in pay-to-play charging stations for events and retail locations. Others, like Philadelphia's own ChargeItSpot, are taking advantage of connection dependence in a better way: by making it free for consumers.

ChargeItSpot creates branded charging kiosks for retail stores where users can lock up their phone while it charges. It's free to consumers because the value lies in keeping customers around (the longer they shop, the more they hopefully will buy) and keeping them happy (they'll associate a positive experience with the brand). They also have an app that alerts users to nearby kiosks when their batteries are low.

"We feel strongly that charging should be free for consumers. It's enough of a service and enough of an engagement that you can drive way more value by making it free and providing it more broadly than limiting it to charging people a fee," CEO Doug Baldasare said.

But ChargeItSpot isn't limited to shopping malls. The charging kiosks have also been successfully placed in emergency room waiting areas at local hospitals, the ultimate place where you need to connect with others and probably didn't think about bringing a charger.

The company's model could easily translate into a citywide project. With the right advertisers on board there's no reason charging stations -- and maybe even Wi-Fi hotspots, if we're getting greedy -- couldn't pop up on street corners like pay phones once did.

"I think we’ve done so much more as a society in terms of technology and how we're able to monetize business models without charging the consumer. Pay phones didn’t have screens with data capture and mobile apps to be downloaded and email addresses to be captured. In today's age, the incremental monetary costs are so low you can make it free," Baldasare said.

"It's something I think is going to explode in the next year or two, just as Wi-Fi has become ubiquitous. Wi-Fi is now expected wherever you go."

Sure, a data-mining branded kiosk system would add yet another element of consumerism to already spend-friendly devices. But if Philadelphia can create a sponsor-based bike share system that is both unique for its equity across demographics and doesn't feel ad-heavy, then why not a way to charge your phone without crouching behind a vending machine? It would be just another notch in the progressive belt of a city kind of known for, you know, founding the nation.