October 07, 2024

Provided Image/Gift of Life

Provided Image/Gift of Life

Cynthia London's son, Sipho, saved six people's lives after his family decided to donate his organs after his death in 1997. London, pictured here at the microphone behind a banner with Sipho's image, educates people about how a more diverse donor pool means better chances of matches for everyone waiting for transplants.

When Cynthia London's son was shot five times and ended up on life support in 1997, she was determined to put his name, Sipho Themba, which means "gift of hope," into action.

"The doctor said, 'That's all we can do,'" London said. "And then we prayed about it for two days. … I just didn't want him to go without having done something."

London and her family decided to donate Sipho's organs and tissue to people who needed them. In death, Sipho saved six other people's lives.

London became an ambassador for the Gift of Life Donor Program, one of the organizations that coordinates organ and tissue donations throughout the country. Using her experience as a donor mom, London helps educate people about organ donation in general. But London, who is Black, also focuses on raising awareness about the benefit of having more organ donors among people of color.

Organs are not matched based on race or ethnicity, and people from different ethnic groups frequently match one another. Yet, blood type and tissue markers needed for compatible donation are more likely to be found among members of the same ethnicity. The chance that someone in need of a transplant finds a match increases as the donor pool becomes more diverse, federal health officials say.

About 60% of the more than 100,000 people waiting for transplants in the United States are from people of color, according to according to Gift of Life. People of color made up 33% of deceased and living organ donors in 2023.

Sipho's heart went to a white man who lived another 22 years. He returned to work, watched his children grow up and became a grandfather. This emphasized for London that "it doesn't matter about color, it doesn't matter about any of the 'isms,'" she said. "We just have to understand that we are humans first, and we have to move forward with that."

For decades, Dr. Clive Callender, a professor of surgery at Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, has been dedicated to increasing the number of minority donors and to boosting disease prevention and awareness about issues that contribute to people needing transplants. With this twofold solution to the donor shortage in mind, he founded the National Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Education Program in 1991.

"We have two kidneys, and some would argue that the other kidney is for donation to somebody else," said Callender, a professor of surgery at Howard University College of Medicine in Washington.

Historically marginalized communities, including people of color, have been disproportionately impacted by inequities in the health system caused by systemic racism and more limited access to top-quality medical care and education. These factors have contributed to steeper rates of chronic health issues, such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease, conditions that can result in organ failure.

Black people are three to four times more likely to progress to end stage renal disease for chronic kidney disease than white people, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Kidney failure results in a reliance on dialysis, a medical treatment that removes waste products and excessive fluid from the blood. Many people with end-stage renal disease seek a kidney transplant, and there is a greater demand for kidney donation than for other organs.

Although there is some risk of developing high blood pressure, donating a kidney does not alter life expectancy and does not seem to increase risk of kidney failure, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Only one healthy kidney is needed to replace two failing ones.

Black people are approximately four times as likely as white people to develop kidney failure, but Black patients are less likely to receive transplant evaluations, according to a 2022 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. They are half as likely to be put on a transplant list and more likely to die on the kidney transplant waitlist.

It wasn't until 2022 that the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network adopted a measure requiring transplant hospitals to use a race-neutral calculation for estimating a patient's kidney function level. Some hospitals had been using a formula that included race as a factor, disadvantaging Black transplant candidates by overestimating their kidney function.

"Dropping of race from the kidney formula has led to more African American patients being referred to kidney doctors" and being referred for transplants, said Dr. Pooja Singh, enterprise director for Kidney Transplant Services at Jefferson Health.

Healthy people who meet the required physical and mental health criteria are able to donate one kidney. Less frequently, living donors give a piece of several other organs, including the liver, lung, pancreas and intestine. Living donors also can give tissue, such as skin, bone and healthy cells from bone marrow, as well as blood and platelets.

Living donations make scheduling easier and decrease transport and storage time for organs, reducing the chance of complications. Transplants from living donors are associated with longer survival of the donor organ, according to the Mayo Clinic.

But though nearly 29% of people waiting for transplants in 2021 were Black, just over 15% of organ donations came from Black communities. About 81% percent of donor organs from Black people were from deceased donors.

Part of the reason for this discordance is because Black family members are not approached as frequently or in the same way as white people regarding organ donations, and Black people more often view these interactions as fraught, according to the National Academies report.

When London tries to educate people about organ donation, she finds that some people fear that "if something should happen to them, they won't be taken care of," she said. "But they don't realize that the doctors take an oath to save lives. It's all about saving lives."

A lack of trust in the medical system, built through a history of discrimination in the United States, may dissuade some people of color from becoming organ donors. A 2006 study — one of the largest to compare the perceptions and attitudes of Black people and white people about organ donation – found that "although African Americans are not as positive about organ donation as whites, the majority state that they would be willing to donate; this is in striking contrast to real donor rates that hover around 30%." The researchers also noted that Black people who responded to the survey expressed a "pervasive mistrust in the health care system, including its equity."

"Until we address some of these issues, the rates of African American donation may continue to be low," the researchers wrote.

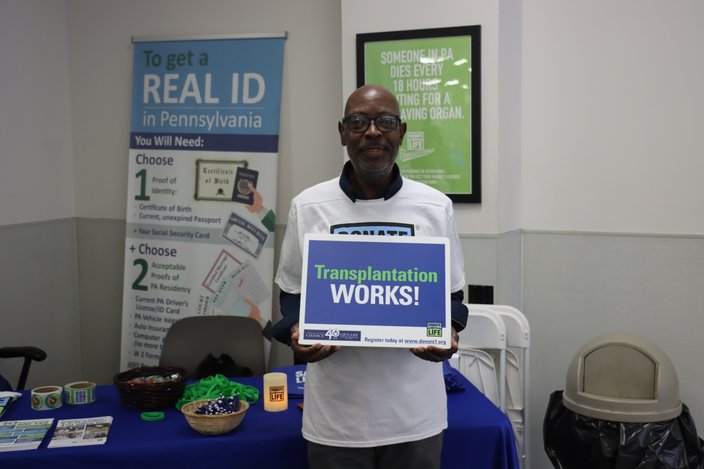

Earl Jones, a Philadelphia resident, had a successful heart transplant 22 years ago. Now he works to raise awareness about the need for organ donation.

A desire to combat this mistrust if part of what motivates Earl Jones, a Philadelphia heart transplant recipient, to tell his story through the Gift of Life. Organ donation "is the most selfless thing a person can do," said Jones, who was told his new heart would give him about eight more years.

That was 22 years ago. Since then, Jones has remarried, dropped 150 pounds and actively participated in the lives of his children and grandchildren. His new heart revolutionized his perspective on life.

"I don't crave a lot of material things," Jones said. "I value my time over everything, and I try to stay present in the moment. I have this laid-back attitude about things."

The mental health benefits for living donors are "immeasurable," Callender added. "It is in the act of giving that you receive. ... When you're healthy enough to give, that is a gift that keeps on giving."

Provided Image/Gift of Life Donor Program

Provided Image/Gift of Life Donor Program