November 22, 2022

Karen Schiely/USA TODAY NETWORK

Karen Schiely/USA TODAY NETWORK

The new COVID-19 boosters that target the omicron subvariants are more effective at preventing infections than the original vaccines, real-world data shows. But some scientists say the benefits are modest at best.

The new COVID-19 boosters that target the omicron subvariants are more effective at preventing infections than the original vaccines, according to the first real-world data released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

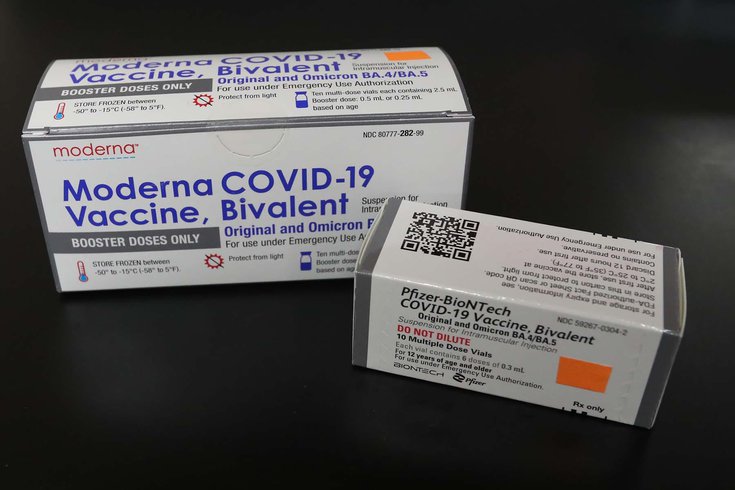

The new bivalent boosters from Pfizer and Moderna were designed to target two omicron subvariants and the original coronavirus strain, in hopes of preventing a COVID-19 surge this winter. The data shows they outperform the original vaccine, but don't completely prevent infections.

The CDC report is based on data from more than 360,000 adults who were tested for COVID-19 after developing symptoms between Sept. 14 and Nov. 11. The omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.5 were the dominant strains at the time.

Of the 121,687 people who tested positive for COVID-19, only 5% had received the bivalent booster. Another 24% were unvaccinated and 72% had received several doses of the original vaccine.

Still, only 11.3% of the U.S. population has received an omicron-specific booster shot, according to CDC data. That pales in comparison to the 68.7% that has completed the primary series.

Overall, the omicron-specific booster shots better prevented infections among people of all age groups. But they offered the best protection to people who waited longer to get the booster after having received the original vaccine or their last booster shot.

Here's how effective the omicron-specific booster shots were based on a person's age and the time since their last dose of the original vaccine:

| Time since last COVID shot | Ages 18-49 | Ages 50-64 | Ages 65+ |

| 2-3 months | 30% | 31% | 28% |

| 8+ months | 56% | 48% | 43% |

Previous studies have shown that waiting longer between COVID-19 vaccine doses can lead to higher antibody levels.

Dr. Francesca Beaudoin, a clinical epidemiologist at Brown University, told The Washington Post that the benefits of the omicron-specific vaccine are real, but modest at best. She said the study's findings are "underwhelming" and leave more questions to be answered, including how effective the updated booster is against preventing severe disease compared to the original vaccine, and what the goal is for the new booster.

Dr. Ofer Levy, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children's Hospital, had a similar assessment. He told NBC News that the new booster shots' effectiveness isn't "stellar." But he said it is "something," noting it outperforms the original vaccine formulation.

The CDC currently recommends that people age 5 and older get an updated booster at least 2 months after their last dose. People who recently have had COVID-19 are advised to delay their booster shots until they are no longer sick or in isolation. They also may consider delaying it for 3 months after infection depending on their risk factors for severe illness.

Earlier studies from Pfizer and Moderna showed the effectiveness of their update boosters in a laboratory setting. But this was the first to show how they perform in the real world. Both companies' omicron-specific boosters were authorized by the Food and Drug Administration in late August without any data from human clinical trials.

The study has several limitations, including potential bias in the self-reporting of vaccination status and the underreporting of previous COVID-19 infections.

Some experts have raised concerns that the boosters are good at targeting the BA.4 and BA.5 strains, but that it is not clear whether they protect against the new subvariants, BQ.1.1 and BQ.1, that are now on the rise in the U.S. But many say they should provide at least some protection against the new subvariants.