August 15, 2016

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

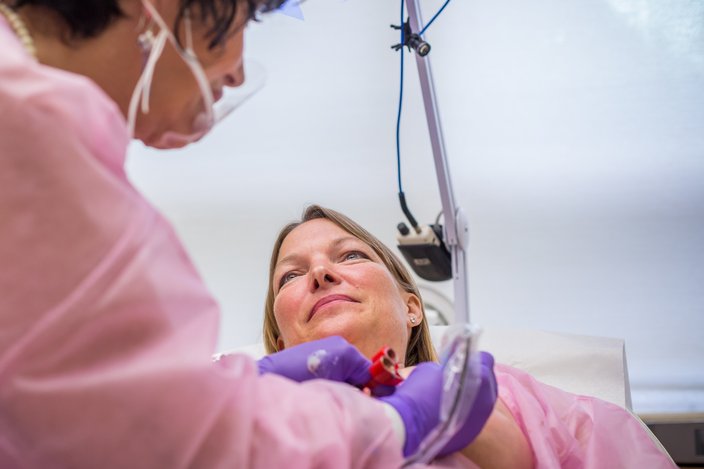

Beau Institute founder Rose Marie Beauchemin draws an areola outline on the breasts of Bucks County native Janine, who's come in for a touch-up. On Oct. 26, The Beau Institute will offer complimentary areola tattoos for those who've undergone mastectomies.

Bucks County native Janine, at 42, had just undergone a double mastectomy to treat her breast cancer. About to shower for the first time since the procedure, she found herself in her bathroom, peeling bandages from her breasts, staring in the mirror, horrified.

"They put these almost like sanitary napkins on your breast when you have the double mastectomy, and when I took them off the first time to see what the surgery did, it was just traumatic," Janine told PhillyVoice. "Absolutely traumatic. It was months and months and months before I could get anything done to make them look like they were feminine.

"It would be like taking your masculinity and throwing it away. 'How do I rebuild from this? How do I put a dress on again and feel feminine, feel sexy.'"

Janine was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011. She got the call while sitting in traffic, immediately in a state of shock that endured through the next three weeks, during which she'd undergo a string of doctors' appointments and her double mastectomy. She hardly realized in her state of awe, she said, what it actually meant to not have breasts — or, moreover, to not have nipples.

Even after she received breast implants, she explained, she still felt incomplete.

"Having the fullness, looking at your breasts without the areola, it's very foreign-looking," she said.

A template used to outline areolas.

She tried stickers (they're like pasties) that ultimately weren't satisfying; she asked about grafts but was not a candidate (a combo of being too skinny and her original areola being plagued by cancer). One option remained: a tattoo technique that created a permanent illustration of areolas in her flesh. Eager to feel like herself again, and comforted by the fact that she had tattoos already, she was willing to give it a try.

So, after researching professionals in the area, off to Burlington County's Beau Institute she went — and out she came with a 3-D nipple tattoo.

“I felt amazing — I remember coming home and being like, ‘Honey!’ And flashed [my husband]," she laughed. "You look like you have everything back.”

The Beau Institute is a permanent makeup clinic and teaching school founded in 1990 by Philly native and former makeover artist Rose Marie Beauchemin. She was encouraged by a New Jersey plastic surgeon to learn and perform the procedure for his cancer-surviving patients in the ’80s. Back then, the technique that was virtually unheard of on the East Coast.

Skeptical at first, she was won over when she saw what it meant to the women coming in for the procedure, and opened her office soon after, performing permanent cosmetic procedures (think: reconstructed eyebrows for chemo patients), camouflage procedures and, of course, 3-D areolas.

It's only recently, Beauchemin told PhillyVoice, that breast cancer patients haves started flocking to people like her for the tattoos.

"Years back, if a woman didn’t have a nipple that was grafted by the surgeon, she didn’t feel complete," Beauchemin said. "But women talk, and as they do, they found out that if there is too large of a nipple graft, it’s going to peek through everything. It‘ll show through all their clothing because it never retracts. The trend shifted to having no nipple and then something that looked like a nipple, which was the 3-D effect."

Rose Marie Beauchenin touches up Janine's left-breast areola tattoo. The touch-up process takes about an hour and is 'like getting your teeth cleaned,' Janine said. Recovery is about 10 days.

Importantly, she said, the trend toward tattoos was largely attributed to the stress that grafts added to women who were already traumatized.

"The thought of a nipple graft, another surgery, just puts [a cancer survivor] over the edge," Beauchemin said. "And now they’ll walk into Beau and they will tell us, ‘I haven't looked in a mirror for seven years.’ It’s heartbreaking. So we go ahead and tattoo the areola, and it’s like tears of joy – seriously.

"What it does for a woman in making her feel whole again is pretty amazing.”

Here's how it works: Beauchemin uses a digital pen that's much smaller than a standard tattoo machine and has finer needles. It is, she said, "like a paintbrush" — often used on clients who have never had a graft, but also on women who have but either have discolored nipples or ones that are not symmetrical. To create the 3-D effect, she uses inks that contrast with light and dark colors and employ a halo effect so as to create the "illusion of protrusion." She even reproduces Montgomery glands, the little bumps in the areola that give the nipple texture.

The Beau Institute's Rose Marie Beauchenin, who studied the practice of cosmetic tattoos in California in the '80s before bringing it to New Jersey.

In Janine's case, the tattoo has been one step forward for her in her recovery process as a breast cancer survivor with PTSD.

"People don't think of breast cancer survivors having PTSD, but they do. It's real," Janine said. "I had a lot of depression at first and a lot of body-image issues I was going through. My husband and I had a lot of marital problems because of it. Because I wasn’t — I was just questioning a lot of stuff. It’s hard when you go through cancer, just to go through cancer, but then to also lose your femininity... all your female parts and everything else that comes with it."

According to a study published earlier this year in the Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 82.5 percent of women experienced at least one PTSD symptom after breast cancer diagnosis but before treatment; one year after diagnosis, 57.3 percent of the women still experienced slightly more than one symptom, with about 2 percent qualifying for a full diagnosis.

Dr. Curtis Miyamoto, chair of the Department of Radiation Oncology at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, told PhillyVoice that medical professionals have only recently formalized the stressful experience cancer survivors endure in the form of research and terminology, but that doctors have long been treating symptoms like depression with a PTSD-like approach.

Ink used for areola tattoos.

“We’ve been aware that women with breast cancer have depression and tiredness, and all the things that come with PTSD, for a long time. So even though we’re calling it PTSD right now, the truth is we’ve been aware that women do suffer, who’ve been diagnosed and treated, for decades," he told PhillyVoice. "Now, we’re labeling this and being able to more formally address it and identify the percentage of women who suffer from PTSD after [treatment]. In the past few years, it's become contemporary to use that term."

Because of how recent that acknowledgment is, however, little research has been done on how, for example, breast augmentations and 3-D areola tattoos benefit women who suffer from PTSD. (Thus, making insurance coverage tricky.) But, Miyamoto said, it has been established that appearance — for women, in particular — has been a proven factor for cancer-related PTSD, citing that, for example, men do not experience that same physical changes when they undergo treatment for prostate cancer.

For Janine, she's made remarkable progress in the five years since she underwent her mastectomy — learning to cope with the come-and-go depression, infertility she's experienced and the loss of her breasts. And though the tattoo, she admits, doesn't make her feel exactly the same as she did before, it has helped her take one step forward to the light at the end of the tunnel — one she says she's "about halfway through."

As she undergoes a touch-up on her tattoo one Wednesday afternoon at the Beau Institute, she pulls down her top to unveil a back tattoo that continues to evolve as she recovers from her trauma. It consists of two beautiful water lilies that dangle down from her shoulder: one for each breast.

A tattoo of water lilies on Janine's shoulder.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice