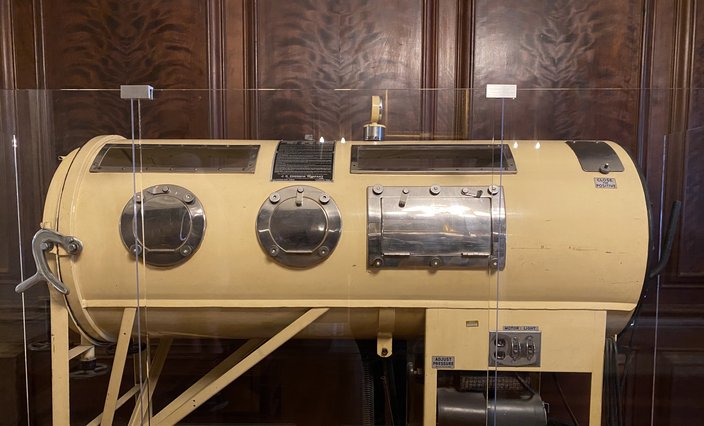

One of the first things a new visitor to the Mütter Museum will encounter is an iron lung dating back to the 1940s. The mechanical respirator, which was used to treat patients with polio and other diseases that impaired their natural breathing, is located on the first floor, just across from the reception desk. Ensconced in a glass display case, the cylindrical device is enormous. Metal portholes and window panels dot the sides, allowing access to and eyes on the person inside. Because once the iron lung was shut and secured with its sturdy metal latch, the patient was essentially trapped until a doctor or caregiver opened it back up.

- INSIDE THE ARCHIVES

- PhillyVoice peeks into the collections at different museums in the city, highlighting unique and significant items you won't typically find on display.

In 2023, iron lungs are mostly a relic of the past, made obsolete by the polio vaccine and other respiratory devices, such as CPAP and BIPAP machines. According to the museum's display, only two people in the U.S. still use iron lungs as of 2020.

But further into the museum, nestled in its entirely on-site archives, is a more compact and modern version of the device. Invented by a polio survivor in 1975, it's smaller, lighter and more stylish, painted in a pale blue rather than drab browns and tans. It's called the Porta-Lung, and for a handful of patients with unique afflictions, it makes everyday life possible.

One of those patients was Gretchen Stoffel, who upon her death in 2022 donated her Porta-Lung to the Mütter Museum, at 19 S. 22nd Street in Center City.

Stoffel suffered from a rare neurodegenerative disorder called riboflavin transporter deficiency, but she didn't have that diagnosis for much of her life. Beginning at the age of 2, Stoffel started experiencing terrifying incidents where she stopped breathing, resulting in multiple hospital stays and an emergency traecheostomy. After a year of shuttling between doctors, none of whom knew exactly what was wrong with her, Stoffel's parents tried an iron lung on the advice of an "old gentleman doctor" who had worked with the devices. Little Gretchen slept in one for years, eventually improving enough that her doctors weaned her off it. She resumed nighttime use around the age of 13, after her hearing, sight and muscular strength worsened, but was off the iron lung again by her 20s, when she traveled abroad to Europe and the USSR with an ASL interpreter.

"She could kind of sleep short bits of time because (her condition) was degenerative, so her body used to be stronger," Jody Groff, a long-time friend and eventual caregiver of Stoffel, said. "She just kind of sucked it up. And when you're 20, you can go without sleep more than you can when you're 30, 40 or 50."

The Porta-Lung came into Stoffel's life in the '90s. The device was the invention of Sunny Weingarten, a polio survivor who created it after using an iron lung for 38 years. Since an iron lung can weigh up to 650 lbs, it had anchored Weingarten to his parents' home all his life. But with his new lightweight model, weighing just 100 lbs, he could finally get his own home and lead a more independent existence. New pulmonary technology was already available by that point, but part of the appeal of the Porta-Lung for Weingarten was that it didn't require a mask. This was also a boon for Stoffel, who could not remove a mask on her own due to contractures in her hands.

Like the iron lung, the Porta-Lung generates pressure and then applies it to stimulate the natural expansion of the user's lungs. This system of negative-pressure ventilation differs from the positive-pressure ventilation delivered through the tubing and masks of CPAP and BIPAP machines. The user's face is free in a negative pressure ventilator, since the head hangs out of an opening on one end of the cylinder. The rest of the body, however, is encased in the machine. To signal for help, a user might employ a whistle or, in Stoffel's case, an electronic doorbell her caregivers added inside the machine.

Even with the device's limitations, users found ways to make the Porta-Lungs more comfortable or personal. Beth Coffin, a young woman suffering from spinal muscular atrophy type II and scoliosis, covered hers with flower stickers for added cheer, according to a 2011 article in the Lewiston Sun-Journal. With the help of her handy father, Stoffel had a piece of trim installed to prevent her mattress from rocking as she turned in the night. A towel stuffed underneath the mattress provided additional security.

"I told her she was like the Princess and the Pea because she could always tell if something was wrong," Groff remembered. "She would say, there's something wrong with the towel under my mattress. And her dad would say, no, there's not, that's not possible. And I would get in there and take the mattress out and sure enough, one little corner would be folded the wrong way."

- MORE INSIDE THE ARCHIVES

- Mr. Potato Head's forgotten friends from the 1960s live in Philly at the Please Touch Museum

- Story of a pioneering queer writer's audacious love life is preserved in the Rosenbach collection

- This 5,000-year-old stone tablet at the Penn Museum is among the oldest examples of writing in the world

The Porta-Lung originally was distributed by Lifecare in 1988 and later, after the company was sold in 1996, by Respironics. It changed hands again in 2007, when Philips acquired Respironics for $5 billion. The new owners announced they were halting distribution of the Porta-Lung the following year, making maintenance increasingly difficult for the remaining users.

Groff recalled finding spare computers stockpiled in a closet after Stoffel's father, her primary caregiver for most of her life, died in March 2022. Gretchen died just six months later in Lansdale, Montgomery County. She was 61, exceeding the expectations of so many doctors throughout her life — a life that included ballroom dancing, frequent trips to Disney World (with the Porta-Lung in the back of the car) and a career in computer programming.

For now, the Mütter Museum has no concrete plans for her Porta-Lung. But staffers say acquiring it was a "no-brainer," given the iron lung and other medical devices already in the collection.

"We kind of have a whole history of the pulmonary system devices now," Lowell Flanders, collections manager and registrar, said. "We have one of the earliest ones from World War I, the Dräger Polmotor, which was used to apply oxygen when someone got gassed with mustard gas, or for any other sort of respiratory disease. And then we have two or three respiratory devices leading up to the iron lung. They weren't for you living in; they were very short-term to help you breathe in an emergency."

Those devices could be dusted off and taken out of storage sooner rather than later as the Mütter Museum considers its future direction. In its 160th year, the museum is undertaking a two-year project it's leaders are calling Post Mortem, which will reexamine its approach to displaying human remains.

Critics of the museum, which grew from the personal collection of Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, say many of the skulls and organs in its collection came from people who did not, or could not, consent to their donation. During her two-year tenure as museum CEO, Dr. Mira Irons launched an initiative to reconsider the approach to these artifacts. This sparked outcry from groups like Protect the Mütter, particularly after the museum removed its online videos and exhibits earlier this year pending an ethical review. A new online database was created in August, omitting any images of human remains.

As the museum staff awaits the results of its Post Mortem, endless stories about medicine, the human body and people like Stoffel lie waiting in the collection to be told. Their friends hope the artifacts from their lives will highlight the importance of medical technology, no matter how seemingly antiquated or specialized it may be.

"It's easy to say technology doesn't matter when it's somebody you don't know," Groff said. "And if it's five or six people in the planet, you're like, well, it's unfortunate for them, but some people have a survival of the fittest attitude. We don't really live like that. We have a son with special needs, and we see what he offers the world. Everybody has a place. And so I'm really grateful for the people who take the time to figure out ways to make life good for people who otherwise wouldn't live."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.