May 19, 2023

Open Knowledge Commons/U.S. National Library of Medicine

Open Knowledge Commons/U.S. National Library of Medicine

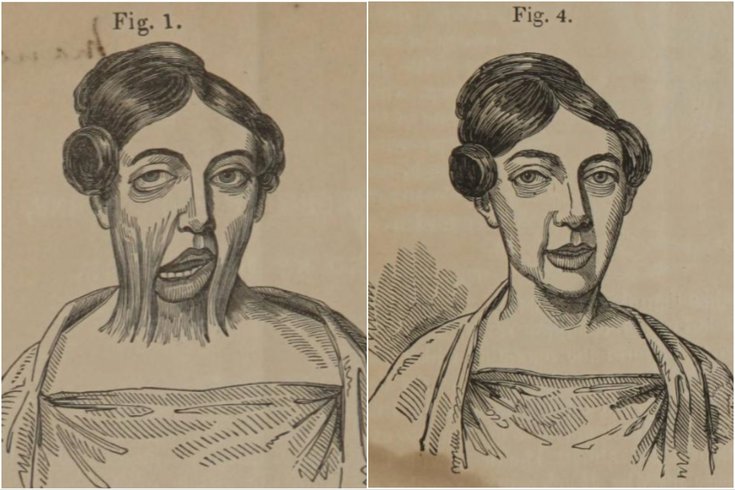

Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter recorded the case of "Miss A. T." (illustrated above) in his publication on flap surgery for burn victims.

Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, who practiced medicine in Philadelphia in the 1830s through the 1850s, is mostly associated with the Mütter Museum, a collection of wax models, skeletons, preserved organs and other medical curiosities housed inside the stately College of Physicians of Philadelphia building in Rittenhouse Square. But during his lifetime, the plastic surgeon and Jefferson University professor was known for his daring procedures designed to help those shunned by society — including the so-called Mütter flap.

The Mütter flap was a revolutionary surgery intended to help burn patients. Between the open flames in kitchens and gas lamps used for lighting, fires were fairly common in the 19th century, and given the extremely flammable materials used in clothing, women were especially susceptible to horrific burns.

As detailed in Mütter's 1843 publication "Cases of Deformity From Burns, Successfully Treated by Plastic Operations," several of his patients had suffered their injuries as children and, absent any proper care, they had only worsened. Their scars had stretched and tightened into contractures, which limit movement, making daily life difficult and often painful.

This was an especially awful predicament for people who had burned their necks or faces. Some of Mütter's patients had not been able to turn their heads or close their mouths in many years, and their appearances had changed so dramatically that people often dismissed them as "monsters."

Many were deeply depressed. While preparing a young woman, who lived with her contractures for 23 years, for the painful surgery, Mütter recalled, "To this my patient readily assented, declaring that death were preferable to a life of misery such as hers."

His solution was a grafting procedure that used healthy skin from the patient's back. The surgeon would make an incision along the upper back or shoulder, carving out a "flap" that could be pivoted over the patient's contractures and stitched into place on similarly healthy skin below or next to the affected area. The back incision would be sutured and dressed with straps, pins and/or "lint moistened with warm water" before the patient was sent to rest. A doctor would make frequent check-ins over the ensuing days to watch for signs of fever or infection.

The "most shocking wounds," as Mütter called his incisions, could be as large as 6 1/2 by 6 inches, and all of this was done without anesthesia. If a patient cried out mid-operation, only water and wine were given for relief.

But the results were astonishing. Miss A. T., the patient who longed for death, gushed about her new life in a letter to the doctor:

"The comfort and satisfaction I feel cannot be expressed; your exertions in my behalf have been blessed far beyond my most sanguine expectations. You have set my head at liberty, so that I can turn it any way, at pleasure, and without pain; you have relieved the drawing of my eye; and I am also enabled to close my mouth with comfort, a blessing that cannot be described!"

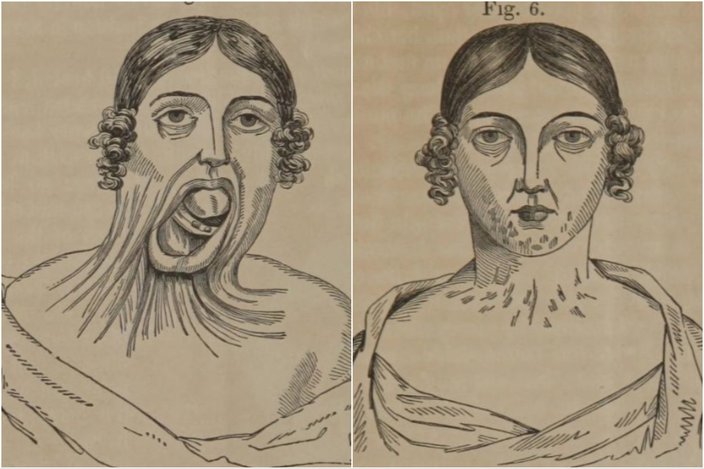

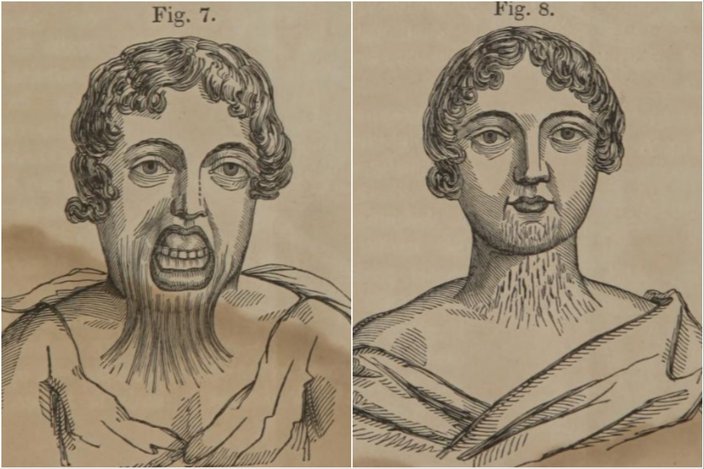

Mütter reported similar success with Margaret Ann Henderson, a 12-year-old girl whose contractures had turned her lower lip inside out and drawn her chin nearly down to her sternum, and Charles McAllister, a 9-year-old boy whose chin was stretched down towards his chest and whose mouth was "permanently open." All three cases were illustrated vividly in his medical text, which referenced three other successful cases in a May 20, 1843 editor's note.

Illustrations of Dr. Mütter's patient Margaret Ann Henderson show her condition before and after surgery.

Charles McAllister, a nine-year-old patient, could not close his mouth before his Mütter flap surgery.

Mütter died at the age of 48 but spent much of his short life helping people like Miss A. T., Margaret Ann and Charles. These "tortured people," his biographer Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz writes, who suffered accidents and medical calamities were branded as beasts by their communities. They were the only individuals willing to seek such "radical surgery," she explains, out of desperation for relief.

Through his drastic, but effective, operations, Mütter was one of few who could give it to them.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Open Knowledge Commons/U.S. National Library of Medicine

Open Knowledge Commons/U.S. National Library of Medicine Open Knowledge Commons/U.S. National Library of Medicine

Open Knowledge Commons/U.S. National Library of Medicine