July 07, 2015

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

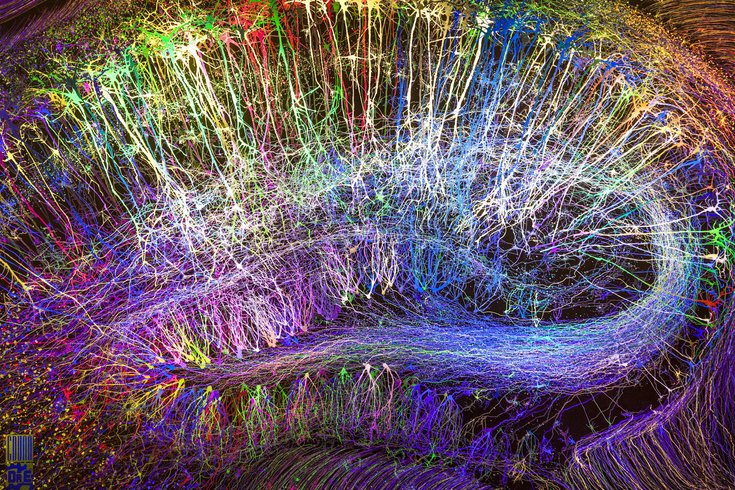

Brainbow Hippocampus, Greg Dunn and Brian Edwards, 22K gilded microetching in custom frame, 2014.

The artwork of Greg Dunn starts off simple, typically with circular blobs of liquid black ink on a piece of paper. With a few strong puffs of air, the blobs grow finger-like tendrils that stretch outward — and in turn, those tendrils split off into even smaller branches. Eventually, the paper is covered with what looks like a leafless, black forest.

This ink blowing technique, discovered as a happy accident by Dunn, turns out to be the perfect way to mimic the sprawling, fractal-like complexity of neurons. Instead of a brush, he blows on droplets of ink through a thin tube to depict the shape of neurons and their branches, called dendrites. Dendrites receive messages from other neurons while an elongated trunk known as an axon takes information away.

PHOTO GALLERY: Artist recreates the inner brain

The average person's brain has about 80 billion neurons, all firing as an intricate and coordinated symphony to create the human experience — a concept that is at the core of Dunn's work.

“I'm in a niche that contains subject matter of fundamental importance to every human being on the planet,” he said. “We all have brains, and brains govern everything we do.”

Dunn is not your run-of-the-mill fine artist. Instead of going to art school, he experimented with painting during his time as a neuroscience graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania. He received his Ph.D in 2011 and has worked as a full-time professional artist since. Aside from his paintings, he also uses a reflective microetching technique that he invented in collaboration with Penn physicist Brian Edwards. Microetching allows flat surfaces to be seen as three-dimensional by using tiny engraved ridges to manipulate how light reflects off the piece.

A new exhibit featuring Dunn's artwork opened Friday at the Mütter Museum in Center City. Called “Mind Illuminated,” it will display a number of his paintings and microetchings in the Mütter's art space, Thomson Gallery, until the end of December. A free gallery reception will be held Thursday for the public from 6 to 8 p.m.

“We knew we had the space and wanted to do something with a local artist,” said Mütter Museum curator Anna Dhody. “This Thomson Gallery space couldn't be made for a more perfect exhibition.”

Scientists are naturally drawn to Dunn's work, which hangs at Johns Hopkins University, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Society of Neuroscience headquarters, to name a few. In spring, the Franklin Institute will display an enormous 8-foot by 12-foot microetching of neurons that could very well be the most complex artistic piece to depict the human brain.

“It's so intriguing to see scientists who are also artists combining visions from what we have historically thought of as two separate things and really meld them together,” said Mütter Museum director Robert Hicks at a press conference last week.

Originally, Dunn wanted to be a musician; he has played the piano since he was 5 years old. But he always held a fascination with science, and years later decided to focus on neuroscience for graduate school to learn more about the inner workings of the human brain.

“The brain is the linchpin on which the universe rests, at least from a human experience,” he said. “You cannot do or think about anything that doesn't involve your brain in some way.”

While at Penn, he studied a field called epigenetics — the epigenome consists of molecular markers that switch the genome on and off, changing how genes are expressed in cells. Dunn published the results of several mouse studies that explored how epigenetic markers can be influenced by things like stress and diet in a mother and even passed down to future generations. During his time in the lab, he was struck by the chaotic, natural beauty of the images he witnessed through his microscope.

“In grad school, you're just bombarded by these incredible images every day,” said Dunn. “Nature is beautiful on all scales, and there's so much cool stuff in the microscopic world that typically doesn't meet our awareness.”

He noticed parallels between the anatomy of neurons he was seeing and the gnarled trees depicted in East Asian screen and scroll ink paintings. Dunn wanted to artistically comment on those similarities, but quickly found that hand-painting neurons lacked the randomness they show in real life. That's when he stumbled upon the ink-blowing technique.

Early paintings used the technique on traditional long scrolls and gold leaf panels reminiscent of the artwork from Japan, Korea and China. As he worked with gold leaf, Dunn began to notice the different ways it behaved under different lighting and reflective conditions. He had an idea to manipulate the reflectivity of surfaces to alter the way viewers experience a piece depending on where they are standing. With Edwards' expertise, Dunn started working on the technique known as microetching.

Using mathematical modeling, Edwards and Dunn figured out a way to make microscopic ridges in a material at specific angles in order to reflect different amounts of light into a viewer's eye. Parts of the piece can then appear and disappear depending on the angle of view, and it even can incorporate animation. The microetchings are then finished with gold and can be colorized with lights. All in all, perfecting the technique took a year-and-a-half.

The giant piece they are making for the Franklin Institute is a whopping 25 times larger than his current microetchings. It will depict a sideways view of a human brain cut down the middle, in all its glorious detail, and neurons will appear to fire as one walks by the piece. The artwork is being funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Even though he's had success selling his pieces to scientific institutions, Dunn ultimately wants to break into the fine art world — although he expects some initial pushback from the community.

“I expect that there's going to be resistance from the fine art world to this kind of work because I think there's a skepticism in general to science,” he said. “A lot of artists I know are intimidated by the scientific world, and the second science comes into the conversation is when the magic gets stripped away.”

With all Dunn has accomplished in only four years as a professional artist, the fine art world might as well get used to the idea that science can be beautiful.