December 30, 2024

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

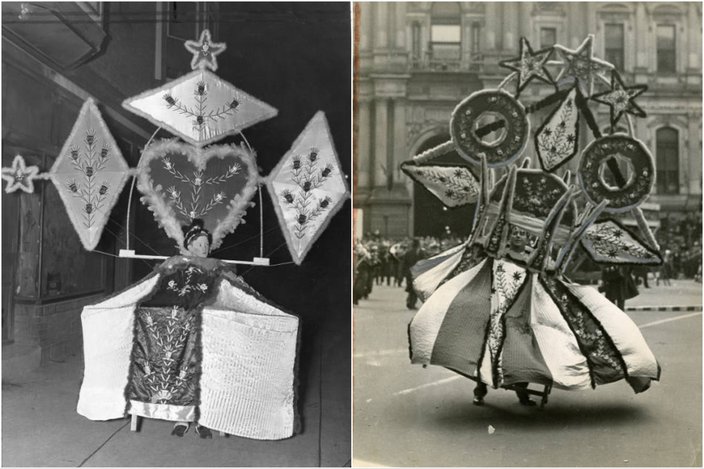

This piece of a Mummers frame suit dates back to 1900-1920. It would have been worn by a Fancy marcher in the New Year's Day parade.

It takes a certain amount of conviction to wear a Mummers costume — but years ago, it also took significant poise and core strength.

This is most apparent in the evolution of the frame suit, a design favored by the Fancy marchers. The elaborate outfit consists of an enormous fabric skirt draped over a structural frame, with still more accents and pieces extending above the Mummer's head. Nowadays, these costumes come with wheels. A century ago, however, the Mummers wearing them had to motor with their own two feet. Given the bulk and weight of these get-ups, which can top out at 300 pounds, wiping out on Broad Street was a major concern.

"It was all shoulder power," said Mark Montanaro, volunteer curator of the Mummers Museum. "You would carry it on your shoulder. And that would be a very brutal day, especially if it was windy."

The Mummers have paraded through Philadelphia on New Year's Day with the city's blessing since 1901. Unofficially, they've been at it much longer. The tradition emerged locally sometime in the 17th century, influenced by folk customs immigrants brought from Scandinavia, England and other parts of Europe. Crowds would wander the neighborhood performing irreverent skits and poems, some of which ended in a demand for alcohol. Sometimes they brought guns, firing them into the air as part of the celebration. Those were banned from the celebration by the time the parade earned city sponsorship.

Masquerade, which was considered an illegal public nuisance in Philadelphia for much of the 19th century, has become the Mummers' calling card over the years. It also makes up a significant portion of the collection at the Mummers Museum. Founded in 1976 as part of the city's bicentennial celebration, the South Philly institute routinely cycles alligator hats and feathery capes through the main exhibit spaces. It also displays the costumes worn by the past year's parade victors in each division — Comic, Fancy, Wench Brigade, String Band and Fancy Brigade — in a ground floor winner's circle space.

Some of the older outfits are tucked away in the archives, protected from the elements by acid-free tissue paper. One frame suit is dated sometime between 1900 and 1920, a gift of the McGlinchey family that belonged to the Silver Crown club.

"Most of today's clubs are passed down from generation to generation," Montanaro said. "I was the first one in my family to do it. I started when I was just 10 years old. And back in the old days, once you did it, it just became part of your life."

An early frame suit like the McGlincheys' would've been hand-stitched, with a wooden structure supporting the fabric. (The Fancy clubs have since adopted collapsible aluminum frames.) Club marshals would accompany the besuited Mummer during the parade as backup muscle against the wind. If the gusts picked up, the marshals moved behind to push their Fancy friends forward. It didn't always work. At least four Mummers tumbled in the blustery 1950 parade, sustaining minor injuries that sent them to the hospital. Later marches were postponed over high winds.

Mummers frame suits like these were difficult to maneuver on windy New Year's Day parades.

Costumes like these have always required a great deal of planning. It starts with a theme, then research into costuming, music and presentation. Once the designers have sketched the outfits, the actual costume-making begins, usually by the spring. Some clubs, Montanaro says, likely already have their theme for 2026.

The Mummers' masquerade has stirred up considerable controversy. The museum has numerous costumes with headdresses and beadwork copied from Native American traditions — pieces that Montanaro says were created with care, not derision. By his account, the Ferko String Band visited a reservation and invited a tribal council back to the band's clubhouse to see their designs before their 2017 performance, which featured tepees and dreamcatchers.

The group also has a long and ugly history with blackface. The practice was officially banned in 1964 only after pushback from the NAACP and a court order. Several Mummers were furious, including the parade director Elias Myers, who resigned over the decision. He later told a crowd of irate marchers outside his home, "It's a shame when a group that has been going up and up the ladder can stop another group of people from having a good time once a year."

As recently as 2020, the Wench Brigade Froggy Carr was disqualified from competition after two members painted their faces black. The incident drew sharp rebuke from then Mayor Jim Kenney, who threatened to cancel the parade altogether.

"It's been outlawed since 1964," Montanaro said. "So if you do it, you're breaking the rules and shame on you."

The museum hopes to demonstrate the Mummers' multicultural membership with an exhibit on Black marchers in 2025. As the parade approaches its 125th birthday, staffers are also planning renovations to the museum's second floor and seeking grant funding to help them digitize their tapes and films of past performances. The clock is ticking on some of the earliest copies, which run the risk of rotting.

Montanaro admits that he and his fellow Mummers are "kind of nuts." But he thinks there's something worthy about putting on a 300-pound sequined suit and strutting along South Philadelphia every Jan. 1.

"When I did it, I loved putting a smile on somebody's face," he said. "And that's what it's all about. It's a parade to celebrate getting rid of the old and bringing in the new."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.