January 08, 2015

PhillyVoice illustration/Photos from candidate websites

PhillyVoice illustration/Photos from candidate websites

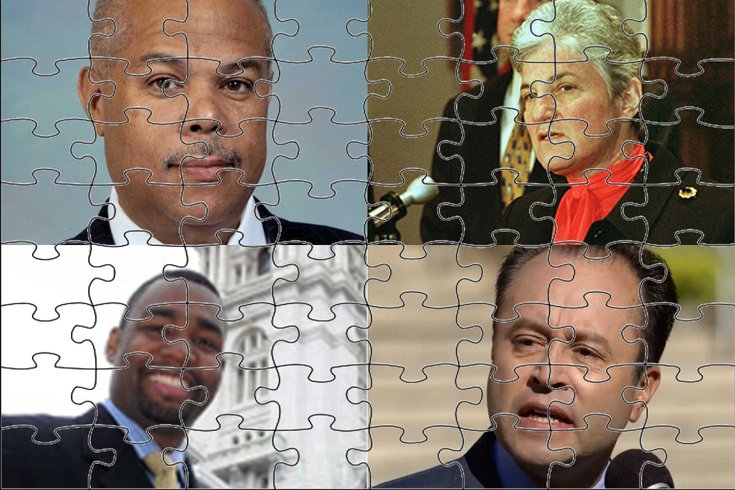

Democrats officially in the race are, clockwise from top left: Anthony Hardy Williams, Lynne Abraham and Kenneth Trujillo. Doug Oliver, bottom left, is expected to announce next month.

It’s not hard to find right now, among those watching Philadelphia’s upcoming 2015 mayoral election, some uninspiring adjectives describing the contest as it stands so far — “uninspiring” being one of them, along with “underwhelming,” “baffling” and “sleepy,” words that suggest that in peering into the upcoming election, there won't be much to see.

Luckily, that's not remotely true.

An open mayoral election in Philadelphia — and they don’t come very often — is less a contest between a few individuals, whether over substantive issues or not, than it is a kind of giant gravitational force, pulling into itself all of the city’s ambitions, frustrations and competing interests as it passes. Into that vortex will be poured millions of dollars in political donations, thousands of hours of sweat and toil, reams of words. And out of it, no matter who the candidates, will emerge the administration and City Council overseeing the $4.5 billion enterprise of running the city of Philadelphia.

"[Millennials and other educated urbanites] could have a profound effect on every citywide election" but only if they show up to vote, which “so far, they have not done.” — consultant Neil Oxman

“Open mayoral races in Philadelphia are always exciting,” says Neil Oxman, a veteran political consultant who managed the mayoral campaign of City Councilman Michael Nutter in 2007. “The mayor’s race is 19 weeks away. Fifteen weeks from now, people will be totally engaged in this race,” Oxman predicts. “One hundred percent engaged.”

So why wait 15 weeks? The field of candidates has yet to settle, but while the candidates themselves matter, they’re also only part of the equation.

Candidates become foils for one another, as they stake out positions. They become virtual walking receptacles of the political money that will, without doubt, be poured into their campaigns by a relative few. They become the faces of different alliances of different groups of people vying for representation and, ultimately, political power.

Whoever the candidates, this election like other elections will be about stories — competing narratives about what the city has been, what it is now, what it should be (and, generally, why the first two don’t amount to the third). And those competing narratives will be there waiting, like tinder for the great frothing cauldron of political stew about to be served up.

That said, sure - it's been, in some ways, a slow start.

As of this publication, six people have either formally entered the race or said they're about to. The three candidates officially vying right now for the Democratic nomination in the party’s May 19 primary election: former D.A. Lynne Abraham, former city solicitor Kenneth Trujillo and State Sen. Anthony Hardy Williams. This week, Doug Oliver, who served for a time as Mayor Nutter’s press secretary, said he intends to officially announce his candidacy in early February. A likely fifth Democratic candidate, former Court of Common Pleas Judge Nelson Diaz, is expected to announce his candidacy later this month. And this week, perennial candidate Milton Street Jr. declared his intention to run as well.

None of the candidates has the kind of big personalities or household names that have sent a shock of energy into many prior mayoral races. Williams carries the name (and job) of his father, Hardy Williams, who served for many years as a charismatic state senator; and Abraham, who served as Philadelphia’s district attorney for nearly two decades, has earned both accolades and criticism for her “tough” approach to law enforcement. Trujillo, Oliver and Diaz will be running as (relative) political outsiders.

In the inevitable horse race analysis, the conventional wisdom seems to hold that Williams’ name, access to donors, and established political network make the race, as they say, “his to lose.” But Abraham claims good poll numbers, Trujillo has intimated access to substantial funds (maybe his own); and Oliver has entered the race declaring his intention to test a “theory,” as he puts it, that there’s no reason he should let having less campaign money stop him from sticking it out to the finish line anyway.

Two other potentially formidable candidates — City Controller Alan Butkovitz and City Council President Darrell Clarke — are not currently running. Either might still change his mind; but a growing consensus doubts it.

It’s still early — maybe very early — with more than two months until the final deadline for new candidates to file petitions (though would-be latecomers can’t fundraise until they announce) and about 19 weeks for just about anything to happen, which it generally has. (Former Mayor Frank Rizzo won the city’s Republican nomination in 1991 only to pass away six weeks later; Nutter was nearly last in the polls until the final weeks of the 2007 election).

In the meantime, while the pool of candidates sorts itself out and political observers watch for surprises, there's already plenty in this election to dig into.

There’s the intriguing question of how Mayor Nutter will play into the mix.

“A new mayor tends to be a reaction to the previous mayor,” notes long-time political observer Larry Ceisler.

Nutter’s election, for example, was widely seen as a reaction by voters to the administration of Mayor John Street. But such “reactions” cut both ways: Street, unlike Nutter, was elected with the blessing of his predecessor in the mayor’s seat; but that mayor, Ed Rendell, had been more popular. Rendell’s election, on the other hand, was widely seen as a repudiation of Mayor Goode’s second term (Rendell had, after all, challenged and lost to Goode four years prior).

Part of what’s intriguing about this election, says Ceisler, is that it’s unclear whether an “anti-Nutter” candidate will emerge — or whether, despite Nutter’s alleged low poll numbers, candidates might not paint themselves as something closer to Nutter 2.0.

Those disappointed with Mayor Nutter’s tenure come, after all, from very different and sometimes diametrically opposed camps. Where business leaders criticized Nutter for not pushing harder on the city’s municipal unions in the wake of the Great Budget Shortfall of 2008, the city’s unions raged against the mayor over the protracted standoff for a contract. Those unions “have basically decided there will never be another Nutter,” one political observer told me.

And on the subject of unions, there’s the question of how, when, to what extent, and on whose behalf (or to whose detriment) those and other unions will get involved in the race. Insiders say that the city’s various labor interests, always sources of the ever-important money that fuels political campaigns, would like to present a unified front — but whether they will isn’t clear. Sen. Anthony Williams’ close financial ties to the pro-voucher Susquehanna Group hasn’t exactly endeared the candidate to members of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers; on the other hand, the degree to which that union is willing to push the issue (especially if Williams’ candidacy is looking good) isn’t clear.

Which brings us to education: an issue of often paramount importance to residents of every stripe — but also vexingly complicated when it comes to the mayor's race. The mayor, after all, doesn’t run the schools; the School Reform Commission does that, and a majority of that body is appointed instead by the governor. School funding, in turn depends partly on money appropriated by the state legislature. The mayor has sway, no doubt, both here and in Harrisburg — but how (if they do) will the candidates campaign around the limitations of their own power?

There’s the question of how (if at all) Philadelphia’s changing demographics will come to bear on the election. The city is growing for the first time in decades, growth fueled largely by immigrants and so-called Millennials and other highly educated urbanites living in the neighborhoods around Center City. It’s a huge change … except, so far, when it comes to political representation. “They could have a profound effect on every citywide election,” says consultant Oxman — but only if they show up to vote, which “so far, they have not done.”

Here’s a potential sleeping giant of an issue: crime. “It’s down,” has been the mantra for most of the past seven years and rightfully so: homicides and other violent crimes have, with a few bumps here and there, been on a downward trend for, essentially, the entire Nutter administration.

But that could change, and the current low is still multiple times higher than the rate of homicides in New York City. And policing, as has been obvious recently, is an issue that goes beyond crime rates. One of the most important hires a mayor makes is his or her police commissioner. And Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey — who has commanded wide-ranging respect for everything from the drop in homicides to restraint in protests and a reduction in police-involved shootings to his willingness to tackle corruption in the ranks — isn’t likely to outstay the next mayor.

There is the tension

between those for whom the city has gotten better and those for whom it hasn’t — with plenty of frustrations over how the city has been run on both sides. How development will shape neighborhoods, how poverty will be fought, how vacant land and tax delinquency

policies will work, whether the city’s pensions will be funded, and how parks, libraries, homeless shelters and health facilities will be re-balanced in the mix — all are up for debate.

And if these are just a few of the many, many issues swirling through this race, don’t forget: we haven’t even touched City Council yet.