March 26, 2018

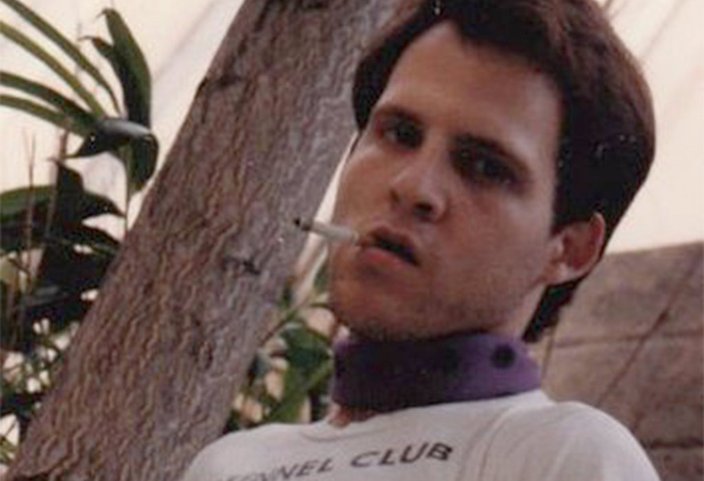

Photo courtesy/Andrew Mars

Photo courtesy/Andrew Mars

“So much risky behavior is just the norm,” Andrew Mars says. “Most of what I've experienced on Grindr is what I’d call harassment. There is a lot of peer pressure to be hyper-sexed and there are a lot of older men who exclusively go after younger men....”

When Jeffrey Sidelsky was in his early 20s, he worked at a popular record store and gay nightclub in Philly. It was around the time that Gloria Estefan’s “Conga” was topping the music charts and virtually nobody was out at work. Nobody. In fact, being gay was still widely associated with AIDS, the disease that was claiming the lives of so many young men in the Philly community.

Sidelsky, who admits that he was never really “in” the closet, says most people at the record store knew he worked at the popular gay bar Kurt’s, but it wasn’t something anyone ever really discussed. “The manager loved Cher and Donna Summer, and I thought he might be gay,” he says. But because everything pretty much stayed in the closet, it never prepared Sidelsky for what happened one night after closing.

He still remembers it clearly. The store was closed and he was vacuuming the showroom before leaving for the night. He was dressed for Kurt’s with a popped collar and moussed hair. “And there was my manager standing in front of me touching himself,” he says. “He said to me, ‘Oh, can you come in and vacuum my office? My office is dirty.’”

Sidelsky was stunned.

“I had this sense that I needed to be leery of him, so I tried to deflect,” he says. “I was not a vulnerable or innocent person who would fall for some kind of line like that. So I let him know that because the office was so small he would need to leave the area – and I tried to do it with humor.”

It worked, but every day after that Sidelsky made it a point to avoid the masturbatory manager before and after closing.

“I’d do a scan of the floor to make sure he wasn’t near the basement elevator,” he says. “One time he appeared out of nowhere, squeezed in the tiny elevator and put his head on my shoulder in an affectionate way. I can still remember that he wore this ratty wig.”

Today, Sidelsky questions whether he, like most gay men, was simply expected to accept certain advances (the manager used to give him free promotional materials from favorite artists like Carly Simon). “Was it tit for tat?” he now wonders.

He also knew that this sort of thing happened all the time, like the shoe store manager who would entice young men to give him blowjobs for new sneakers. It wasn’t shocking or terribly unusual, says Sidelsky. But looking back he admits it does make him question what he might have done if this happened in 2018 – in the undercurrent of the #MeToo movement – knowing everything he knows now.

Photo courtesy/Jeff Sidelsky

Photo courtesy/Jeff SidelskyJeff Sidelsky, circa 1985, when he worked a popular record store in Philadelphia, where he was sexually harassed by a manager.

For one gay man in his mid-30s who works in a white-collar office job in Center City – and who asked that neither he nor his company be identified – defining sexual harassment got pretty murky about two years ago when an experience in his workplace made him rethink everything he thought he knew about corporate politics.

Following what he describes as friendly, maybe even flirty chat, “the janitor at work grabbed me by the crotch, pushed me against the sink and kissed me while I was using the restroom,” he says. Shocked, he remembers saying, “I don’t do this at work” and ran out. “It’s the opposite power dynamic a lot of people would expect.”

“My feelings were first shock, then conflict. Now it’s just uncomfortable.”

After the incident, he spent a lot of time thinking about what he should do, if anything, about the incident. “I talked to a few friends about it,” he says. “My straight female friend was horrified and thought I should report it immediately. My gay friends said that it’s different for us.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), even though LGBT people actually experience sexual violence and harassment at a much higher rate than heterosexuals – they are often far less likely to report it. In fact, 40 percent of gay men, the CDC says, and 47 percent of bisexual men have experienced sexual violence compared to just 21 percent of heterosexual men. And almost half of all bisexual women report having been raped in their lifetimes compared to 17 percent of heterosexual women and 13 percent of lesbians.

While some experts say that hyper-sexualizing the LGBT community is to blame for higher rates of assaults and harassment, there are actually many complex factors as to why this particular community is inordinately at risk. For some people, stigma still plays a role in whether or not they might report an incident, while others may simply not have the support system required or may even blame themselves for what happened. Still others question if the rules are, frankly, different for gay people.

The man who was assaulted in the office restroom (he’s not even sure he’s comfortable calling it an assault) says that he felt very conflicted about a minimum-wage employee possibly losing his job over a miscommunication. “If it were someone in an elevated position, I think, oddly, I would have felt more certain that I needed to report it because the possibility of using that power to do it to someone else would have been too great,” he says. “My feelings were first shock, then conflict. Now it’s just uncomfortable.”

He still sees the man everyday.

Source/LinkedIn

Source/LinkedInThe LGBT community is particularly at risk for sexual harassment and abuse, but there are ways to fight back in Philadelphia, says Amber Hikes, the executive director of the city's Office of LGBT Affairs.

Amber Hikes, the executive director of Philadelphia’s Office of LGBT Affairs, says that while the LGBT community is particularly at risk for sexual harassment and abuse, and that “unsurprisingly, transgender people bear the brunt of this harassment,” employees do have ways to fight back in Philly.

According to a large-scale survey of transgender individuals by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 50 percent of people admit to being harassed at work, and most notably being asked questions about their gender or surgical status. Still others face coworkers making suggestive allusions to their intimate relationships and sexual behaviors. “Although such questions may be asked out of overly invasive curiosity rather than targeted or predatory sexual interest,” says Hikes, “this kind of intimidating questioning about one’s body and personal relationships is a form of sexual harassment.”

“LGBT people are protected from sexual harassment in Philadelphia...." – Rue Landau, executive director, Pennsylvania Commission on Human Relations

The Office of LGBT Affairs is looking closely at the kinds of training and policy changes that can ultimately abate and eradicate this kind of abuse – everything from uncomfortable or offensive commentary about sexuality and gender to actual physical assaults. “LGBTQ employees deserve workplace environments where they can be a part of conversations with coworkers without their bodies and relationships becoming the topic of discussion,” she says.

Unlike many cities around the country (and even the state of Pennsylvania, where one can still be fired for being gay), LGBT employees in Philadelphia have the law on their side. Under the city’s Fair Practices Ordinance, sexual orientation and gender identity are protected classes. If someone is harassed, there are steps that can be taken to protect the victim.

According to Rue Landau, executive director of the Pennsylvania Commission on Human Relations (PCHR), “LGBT people are protected from sexual harassment in Philadelphia in the areas of employment, housing and real property and public accommodations. If an LGBT person believes they were sexually harassed on the basis of their sex, sexual orientation or gender identity they can file a complaint with the PCHR.”

Hikes also encourages people to report the issue to the Office of LGBT Affairs where staff is available to walk community members through the process of filing a report. It should be noted that any complaint must be filed within 300 days of an alleged incident.

“If a member of the LGBT community is facing criminal harassment, violence or abuse,” says Landau. “They should contact the police.”

As a transgender woman, Princess Harmony is at higher risk for assault and harassment on a daily basis. At 26, she admits that she has already been the victim of a rape and stalking. It’s something she works through in therapy and with the help of her family.

“I was raped in my dorm,” says Harmony, a former Temple University student. “I said no, but I was drunk and couldn’t fight back.” She alleges that after she reported the incident to the school, they did nothing.

“The detective they sent to talk to me didn't even contact me back when I attempted to talk to him,” she says, “and nobody at the Temple University Police Department thought it was important that my rapist's name was in the logbook for my dorm – they didn't even think to look for it." Not that it mattered, since the page somehow went missing, she said.

Photo courtesy/Princess Harmony

Photo courtesy/Princess Harmony“Nobody is paying attention to the issues specific to queer people when it comes to sexual harassment or violence,” says Princess Harmony, who says she was raped in her dorm room at Temple University.

“Temple is committed to providing a safe living and learning environment for all members of its community,” he explained in an email. “When we receive reports that any student feels unsafe or threatened we investigate those reports promptly and take appropriate action as quickly as possible.”

Last year, Temple received a state grant that helped to create an anonymous online portal that allows members of the community to report a potential crime. Lausch says the university is also working with student populations that may face unique barriers reporting incidents, including students of color, international students and LGBT students.

Harmony, who now splits her time between Philadelphia and her parent’s home in the suburbs, says that she was never able to find justice or even support.

And she’s not alone.

A recent U.S. Transgender Survey estimates that almost half of all transgender people are sexually assaulted in their lifetimes. Transgender people of color are especially at risk for violence, and many times the perpetrators of these crimes are never brought to justice.

“Nobody is paying attention to the issues specific to queer people when it comes to sexual harassment or violence,” says Harmony, who has been speaking out about her assault for the past year in hopes of inspiring other women to do the same. “The biggest obstacle for trans people in terms of personal safety is the lack of understanding and acceptance.”

Harmony, like many in the transgender community, does not trust the legal system, which she says isn’t built to handle sexual violence or gender and sexual differences. “It would need to reform how it handles sexual violence and establish, concretely, the equality of all people of all genders and sexualities in the eyes of the law,” she says. “The biggest misconception, at least directed toward trans women, is that we volunteered for sexual abuse, and so we should be able to just take it in stride. But we didn't, and we can't.”

For Andrew Mars, 34, being able to talk openly about his most painful experiences has given him power over them. But it hasn’t always been easy in a community that this musician says is very preoccupied with image.

“Many things among gay men are suppressed or repressed,” he says. “So much of the gay male community centers around alcohol which affects how people behave sexually and express their sexual affection.”

As he recovers from a long-term relationship that he describes as “psychologically and physically abusive,” Mars has had to evaluate the way he deals with gay sex and sexuality.

“So much risky behavior is just the norm,” he says. “Most of what I've experienced on Grindr is what I’d call harassment. There is a lot of peer pressure to be hyper-sexed and there are a lot of older men who exclusively go after younger men” in a predatory way.

“So much of the community vibe is hypersexual, so I think that kind of peer pressure affects what we'd think of as consent as well.”

As a child, Mars says he was sexually abused by an older relative. Though it’s not uncommon to be victimized by someone known to a family or even in the family, coming forward with the revelation hasn’t been easy. “Homophobes like to say that gay people were abused which led to our perversion,” he says. “There is already so much shame that gay folks have to wade through, so these experiences rarely get discussed.”

He says coming forward with abuse as an adult is just as difficult. A lot of people in the community don’t want to hear about it, they don’t know what to say about it and they might even think that a victim is making a big deal out of nothing. Victim blaming is common, especially among gay men who tout their sexuality as a source of power and pride. One gay man even suggested that men within the gay community feel entitled to touch one another’s bodies. No questions asked.

The mixed messages can take a toll on a young person coming out for the first time in a community where drugs and alcohol are the norm, where someone who is just starting to navigate what it means to be LGBT is establishing boundaries.

Mars describes his 20s as a time of recklessness. “I know that in my own life the abuse I've received is directly tied in with the risky behavior of my 20s,” he says, “but I also know that these behaviors are prevalent and as a sexually active gay man they are almost impossible not to encounter.” Most men he knows have experienced group sex with strangers, had sex in bathhouses, used illegal drugs during sex and had sex in a blackout.

The power dynamic between two gay men can also sometimes make sexual ethics a bit murky. “Throw alcohol and/or drugs in the mix and consent becomes a gray area,” he says. “So much of the community vibe is hypersexual, so I think that kind of peer pressure affects what we'd think of as consent as well.”

For women, sexual aggression can be just as complex. One bisexual woman in her late 40s (who asked that she not be named because of where she works) says a recent experience has made her question how she shows affection to loved ones.

It happened one night when she went out dancing with a friend. “[My friend] indicated that she wasn’t sure about her outfit,” she says. At the time the woman was wearing a long, silky shirtdress over pants.

“When she opened her coat to show me, I placed my hands on her waist and gave her a playful roar and told her she looked fab.”

“When she opened her coat to show me, I placed my hands on her waist and gave her a playful roar and told her she looked fab,” she says. “When we parted ways that evening, I texted her when I got back to my apartment. I said I hoped I didn’t offend her. She said that I didn’t and was surprised that I would even think that.”

About a month later, she received a text from the friend in the shirtdress – she was accusing her of sexual harassment. “She talked it over with her therapist,” she says, “who encouraged her to tell me how she felt. She became very accusatory and completely went off on me.”

After the incident, she was so upset that she decided to end the friendship. “I blocked her from my phone and Facebook,” she says.

Her own identity as a black bisexual woman tends to dictate how people approach her, she says, and and assess her intentions. Most of the time she is seen as an aggressor even though she has experienced a lifetime of harassment for her race and sexual expression.

“Although I identify as femme, many straight dudes read me as a big ol’ butch dyke,” she says on Facebook Messenger. “I’ve been harassed by women looking for some big black butch meat. And when I go into queer clubs and spaces, it’s assumed I am an ally rather than a member of the community based on my identity.”

The sexual, gender and identity politics at play in the LGBT community may certainly be unique to the community, but they are not unique to relationship dynamics that are all too often defined by assumption about everything from gender to race and sexuality. But as more people come forward to report their own experiences, or even rethink incidents from the past, these questions will continue to evolve and help shape the way people interact regardless of sexual and gender identity.

It wasn’t so long ago, after all, that the gay community sought refuge in the darkness of public parks and restrooms simply to find a fleeting, secret connection. Just as social changes have introduced LGBT rights and same-sex marriage into the social construct, so will discussions about gender and sexual identity that are becoming much more fluid as younger people may not always cling to the labels established by their elders.

The movement to expose sexual abuse in Hollywood and on social media is also having an impact on the LGBT community, even if it’s seldom mentioned in the equation. For some, this will create a safe place to come out about harassment and abuse. And for others it will create a lot more confusion.

For the bisexual woman who says she’s constantly being judged for her looks, romantic interactions and even friendships have become a lot more complicated since she was accused of being too aggressive.

“I think there’s been a lot of emotion floating round as a result of #MeToo,” she says. “I don’t hug friends anymore.”