March 24, 2025

Provided image/Academy of Natural Sciences

Provided image/Academy of Natural Sciences

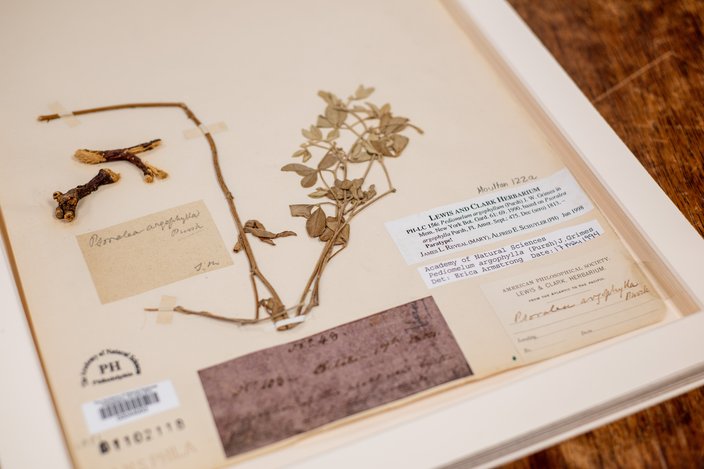

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark collected plants, like this tobacco specimen, during their 1804-1806 expedition across the western United States.

The carefully taped and pressed plants stored in bespoke cabinets in the Academy of Natural Sciences lost their color long ago, but that's understandable. They were plucked from the ground over 200 years ago, when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark explored the western United States.

The Drexel University museum has cared for the herbs, flowers and shrubs the pair found since the late 19th century. While they are typically hidden away from the public in a specially designed room, a few will be on view in 2026 for an exhibit reframing the expedition with Indigenous perspectives.

The story of how the specimens ended up in Philadelphia is a bit complicated, but it starts in 1803, the year before Lewis and Clark embarked on their roughly 8,000-mile trek. By that point, President Thomas Jefferson had already chosen his former secretary, Lewis, to lead this "voyage of discovery." To help prepare him for the demands of the job, the president sent Lewis to Philadelphia for crash courses on medicine, map making and natural science from some of the nation's brightest minds. Benjamin Smith Barton, who wrote the first American textbook on botany, taught him how to identify and press plants on his journey.

"They never documented exactly what kind of press plant they used," said Chelsea Smith, collection manager of the herbarium at the Academy of Natural Sciences. "But we do know what people did back in the day. This would be, when you're out in the field, having two wooden slatted rectangles and having those basically bound together with rope."

Lewis and his chosen copilot Clark, a friend and fellow army veteran, started their expedition from Camp Wood in Illinois on May 14, 1804. Over the next two years, the explorers crossed 16 states, traveling up the Missouri River and across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and back again. They never found the fabled Northwest Passage – a river route believed to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans – but they did collect over 200 plant specimens, 94 of which were new to western science.

Their collection includes trees, grasses, aquatic and flowering plants, herbs and wild rice. The duo even gathered one seaweed – which, Smith is quick to note, is not a plant – in the Pacific Northwest. Though he was new to the field of botany, Lewis demonstrated remarkable dedication to his cataloging duties. Shortly after being shot in the butt, the explorer paused to record a journal entry on the fire cherry, "a globular berry about the size of a buck-shot of a fine scarlet red" with an "agreeable ascid flavour."

When the specimens grew too cumbersome to carry, the explorers buried them and other supplies in deep holes to revisit on their way home. Not all of the locations they chose were suitable storage spots. Spring floods destroyed the plant specimens in a cache site in Great Falls, Montana, as well as the laudanum – and alcoholic tincture made from whiskey and a touch of opium – and bearskins buried with them.

Lewis and Clark didn't do all this work alone. The expedition included various soldiers, French boatmen, Clark's slave York and interpreters like Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who joined the party with her husband Toussaint Charbonneau and infant son Jean Baptiste. Communicating with the Indigenous people who lived in the western U.S. was a crucial part of Lewis and Clark's mission, since they were already experts on the plants the pair were seeing for the first time.

The silverleaf Indian breadroot, pictured above, is a legume with purple blooms native to the Midwestern U.S.

"A lot of what Jefferson had tasked Meriwether Lewis with was to find plants that were useful for some reason, mostly agriculture," Smith said. "He wanted a farming nation and the best way to do that is to interact with Native Americans to figure out, well, what are they using in the land?"

The Academy of Natural Sciences plans to spotlight these Indigenous people in its Botany of Nations exhibit next year. The display, opening in March 2026, will tell the stories of seven Lewis and Clark specimens through the voices of native tribes who lived along the explorers' path. The museum will also "recollect" the plants from the regions where Lewis and Clark found them and press them onto new herbarium sheets.

It's perhaps only fitting that these specimens would inspire one more journey. The collection itself has crossed the Atlantic Ocean multiple times. After the explorers' expedition concluded on Sept. 23, 1806, the plants ended up in Philadelphia under the care of the American Philosophical Society, a scholarly organization founded by Benjamin Franklin. Lewis planned to work with his old mentor Barton on a new book of botany, but the frontiersman unexpectedly died in 1809. Barton passed just a few years later.

The German botanist Frederick Pursh picked up their work, eventually publishing a book on North American plants in 1814. But he also took some of the specimens with him when he left the country. A British botanist then acquired them, but they went up for auction upon his death. A member of the Academy of Natural Sciences donated the plants to the museum in 1856.

Decades later, Academy botanist Thomas Meehan recognized the donations as Lewis and Clark specimens. He knew there should be more, so he went calling on the American Philosophical Society. The rest of the collection was bundled in the attic, misplaced for decades. Thanks to a permanent loan from the APS, the vast majority of the plants were reunited at the Academy of Natural Sciences by the turn of the 20th century.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Provided image/Academy of Natural Sciences

Provided image/Academy of Natural Sciences