February 27, 2019

Photo by Edan Cohen/on Unsplash

Photo by Edan Cohen/on Unsplash

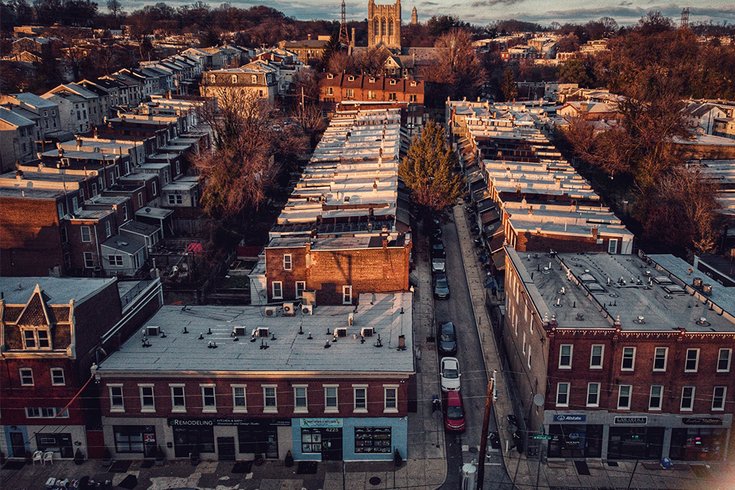

Ridge Avenue in the East Falls section of Philadelphia.

Philadelphia has seen tremendous growth in its real estate sector in recent years, especially in the multi-family rental market.

And while our city’s rent levels remain far lower than those of surrounding big East Coast cities, the average Philadelphian's income is also significantly less than that of those living in New York or Washington, D.C. – meaning that Philly property owners and renters alike are sent reeling when City Council proposes policies that make it more difficult to provide or find affordable housing.

The most recent housing policy to be introduced that would prove detrimental to Philadelphia renters is Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds-Brown’s advancing lead paint legislation. Reynolds-Brown’s bill would require all Philadelphia rental units to be tested for lead, and for units found to contain a certain level of lead, require full remediation. While it’s clear what the councilwoman is trying to do – protect children under the age of 6 from contact with lead, the age at which they are the most vulnerable – her legislation doesn’t apply to just places where kids live; it applies to every unit. And that will have far-reaching and long-lasting implications for property owners and renters throughout Philadelphia.

In fact, the well-meaning legislation could raise rents across the city by as much as $400 a month. The test alone costs $400 and remediation is thousands of dollars more. Those costs are likely to be passed along to renters, especially in any building with a lot of units.

If the city wants to protect children from lead, it should focus on enforcing laws already on the books seeking to prevent unscrupulous landlords from preying on our city’s most vulnerable populations.

And it gets worse – in units where lead is detected, renters could be displaced for at least a few months while it is remediated, even if no children live in the units in question.

Displacement is an overwhelmingly difficult and stressful situation to find oneself in at any given time, and many renters certainly don’t want to be displaced when there’s little danger to them or their health. In a worst-case scenario, renters could be forced out of the apartment and neighborhood they love into a lease for an unlicensed and unregulated apartment that could also have lead paint. How does that make sense, and who pays for this? Stress is also a significant health issue.

On the other hand, in a “best-case” scenario, renters would be able to find a temporary, lead-free place to stay while their home receives the updates needed to comply with the law. But upon their return, these renters will still most likely see their rent rise by a significant amount, essentially making this a lose-lose situation for all renters, no matter how you slice it.

If the city wants to protect children from lead, it should focus on enforcing laws already on the books seeking to prevent unscrupulous landlords from preying on our city’s most vulnerable populations. It just doesn’t make sense to keep passing legislation that will ultimately make Philadelphia’s affordable housing shortage far worse – while not even resolving the problem it set out to address in the first place.

Josh Klein is president of the Pennsylvania Apartment Association East, which calls itself "the leading voice for the apartment industry, providing members professional advancement with a range of strategic, educational, networking, and advocacy resources."