May 02, 2024

Courtenay Harris Bond/PhillyVoice

Courtenay Harris Bond/PhillyVoice

A couple experiencing homelessness and addiction sits on Kensington Avenue on Wednesday, May 1. They say they hope to get into treatment ahead of the impending encampment sweep in the Philadelphia neighborhood.

A man and woman shared food from a styrofoam container Wednesday morning as they sat on the sidewalk of Kensington Avenue, their backs against the metal door of a shuttered storefront.

After moving to South Philadelphia from New Jersey, the couple had to leave the apartment where they were living partly because their roommate was using methamphetamine. Now, the couple is homeless and deep in addiction, using fentanyl "or whatever they put in the bag. You don't know. That's the problem," said the 41-year-old woman, who asked that PhillyVoice only use her initials, G.W.

Meth, a potent stimulant that can cause paranoia, stroke and death, has been sweeping westward across the U.S. It is now prevalent in Philadelphia's illicit drug supply – already toxic with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid approximately 50 times stronger than heroin, and xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer that causes necrotic ulcers and slows down breathing. Xylazine does not respond to the drug overdose reversal medication Narcan, which only blocks the effects of opioids.

Kensington, the site of the largest open-air drug market on the East Coast and the center of Philadelphia's addiction crisis, also holds about 35% of the city's homeless population. Kensington's ZIP code had the highest number of fatal drug overdoses in 2022, a year when the city's overdose deaths spiked to a record 1,413 overall.

Upon taking office in January, Mayor Cherelle Parker declared a "public safety emergency" and issued an executive order in part to "develop a strategy to permanently shut down all pervasive open-air drug markets." Parker's 100-day report calls for a five-phase Kensington revival plan that offers people a "final opportunity to take advantage of shelter and treatment services" before police start arresting people for drug use, sex work, "quality-of-life" crimes and "other criminal acts" in an area from E Street to Jasper Street and Tioga Street to Indiana Avenue, eventually expanding outward.

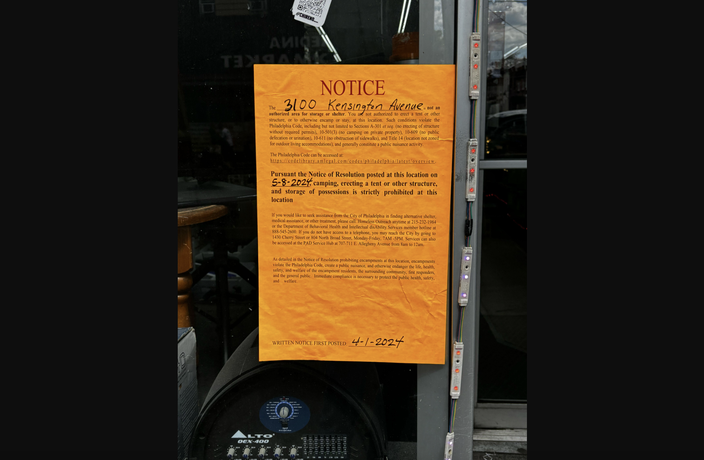

Bright orange notices were posted in some storefront windows, and on some of the pillars of the El roaring above Kensington Avenue, announcing a Wednesday, May 8 deadline for removing tents, shelters and belongings in the area. They also include information for accessing the city's Homeless Outreach and the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services.

"We're petrified," G.W. said about the May 8 sweep.

G.W. said she does "feel bad for the children and the families" in the neighborhood who regularly witness drug use and other traumas.

When G.W.'s partner, G.M., was asked what he thought those with tents and make-shift shelters along Kensington Avenue were going to do, he said, "People are just going to pack their s*** up and move back."

The pending pressure to move and heightened police presence in the Kensington may be a "blessing in disguise," increasing the couple's hope to get help, G.W. added.

"We're trying to get into treatment before May 8 because who knows where they (city agencies) will send us," G.W. said. "We're not happy being homeless."

Signs posted along Kensington Avenue caution that camping and erecting tents or other structures, as well as storing belongings, is prohibited. The city will do an encampment sweep in the area on May 8.

Parker's administration announced Thursday that it would increase the amount of people it could accommodate at a city homeless shelter at 2100 W. Girard Ave. with plans to connect more clients to addiction treatment. City officials did not immediately respond to requests for further information.

The Parker administration plans to invest $100 million to build a system of long-term care, treatment and housing for individuals suffering from addiction, mental health challenges and homelessness, a city spokesperson said last week.

A 27-year-old man named Eric, who grew up in West Philly, said Wednesday that he had been homeless in the Kensington area for the last year or so. He wore a bright red Phillies jersey and carried his belongings – all that weren't stored at his mother's home – in a drawstring bag on his back.

Before he developed a substance use disorder, Eric, who asked that PhillyVoice only use his first name, said he was a tree climber for a landscaping company and saving money for a house. But after his father and brother died, Eric said he fell into addiction.

"Honestly, I'm still trying to work through that," Eric said about the trauma of losing most of his family – and also friends. "I've lost more than I can count on both hands."

A friend from the street asked if Eric knew about a two-week program at a local hospital where he'd heard people received comfort meds to help them detox. Eric didn't. His friend said he wouldn't go to the emergency room to try to find out more about the program because he didn't think he could wait to be seen, fearing the extreme flu-like symptoms of opioid withdrawal.

As his friend walked away, Eric recalled how he was sleeping outdoors in the neighborhood six months ago, and woke up to a group of youths beating him with two-by-fours. He said they broke his arms and cracked his ribs and his skull, requiring 20 staples. The kids probably would have killed him, Eric said, if a man walking his dog hadn't pulled out a gun, dispersing the group.

Eric spent five days at Temple University Hospital before checking out against medical advice. He had a place to sleep most nights but had to walk around during the day with casts on both arms, Eric said.

Across the street, members of Savage Sisters – the nonprofit that provides recovery housing, wound care, outreach and other services throughout the city – tried to revive a person on the sidewalk, using Narcan and a ventilation bag. When Eric saw an ambulance pull up several minutes later, he said, "That's a good thing."

"I'm getting tired," Eric said. "This could be it, honestly. My time's just coming soon – so I can get my life back."

Thin as a stalk, Robert, 26, said he grew up in Kensington at G and East Hilton streets.

"There were a lot of things I wish I hadn't seen, adult things, especially murder," Robert said about his childhood. When he came back to the neighborhood after being discharged from the Marines, the grandmother who had raised him died.

"I guess the trauma, I just didn't want to feel it, so I just got into, you know ... ," Robert trailed off, explaining how he developed a substance use disorder.

He wasn't ready for treatment, said Robert, who asked that PhillyVoice only use his first name. He felt like he would "wind up leaving (rehab) anyway" and did not want to "waste" a shot that he might have better success with later on – even though Robert said he couldn't rest much in his current state because he had to stay vigilant all the time.

"Honestly, a place to sleep," Robert said about what he thought he needed now. "I barely sleep. I just walk around all night."

Courtenay Harris Bond/PhillyVoice

Courtenay Harris Bond/PhillyVoice