For the first time in New Jersey's history, a judge has ruled the corrections officers have a right to force-feed a state inmate who went on a hunger strike to protest the prison's process for dealing with grievances.

On Thursday, State Superior Court Judge Walter Koprowski, Jr. determined that New Jersey has an "overwhelming interest in preserving life" and that 37-year-old William Lecuyer, who has intermittently staged hunger strikes since 2012, must submit to medical examinations and an intravenous nourishment from corrections officers, according to NJ.com.

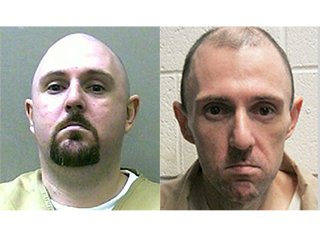

Lecuyer entered the state prison system after pleading guilty in 2000 to robbing a gas station with an unloaded handgun. He also admitted to four other robberies, including a dry cleaner and a laundromat. He was sentenced to 22 years in prison and is due to be released in 2017.

In 2012, Lecuyer was placed in solitary confinement for allegedly refusing to provide a routine urine sample. He went on a year-long hunger strike – subsisting only on water, broth and protein shakes – and dropped from 230 pounds to under 120 pounds.

When Lucuyer was cleared of the urine sample charge in 2013, he resumed eating and gained about 40 pounds, but he continued to suffer from the long-term effects of starvation. In protest of his time in solitary confinement, Lecuyer filed a civil rights lawsuit against five prison officials who he claims infringed his rights and were never disciplined. The suit calls for three of them to be punished, $250,000 in restitution and new due process rights for inmates in New Jersey's prison system.

Since last July, Lecuyer has again refused solid food and medical care, dropping nearly 100 pounds for the second time, according to testimony from a corrections officer.

in court, Deputy Attorney General Nicole Adams argued that Lecuyer's protest was not political in nature, but rather a "suicidal act" based on his unhappiness with a cell assignment. If the state were to concede to his demands, she said, it would set a dangerous precedent for other inmates and disrupt operations at state prisons.

In an interview last October with Forensic Magazine, Lecuyer acknowledged that he deserves his time behind bars, but said should not be denied his rights as result of a bureaucratic system that ignores grievances and fails to provide adequate mental health resources for inmates.

A judge's temporary order granted prison officials the authority to legally force-feed Lecuyer since January, but they testified that the inmate has physically resisted efforts to do so. Adams argued that doctors are needed to rehabilitate Lecuyer to prevent permanent damage to his brain, liver, heart, and other vital organs.

Kunal Sharma, the attorney representing Lecuyer, said he plans to challenge the ruling. He says court failed to hear testimony from witnesses on behalf of his client and cited the World Medical Association's opposition to practice of force-feeding inmates.