May 24, 2023

National Aviary/Arthur A. Allen/Ecology and Evolution

National Aviary/Arthur A. Allen/Ecology and Evolution

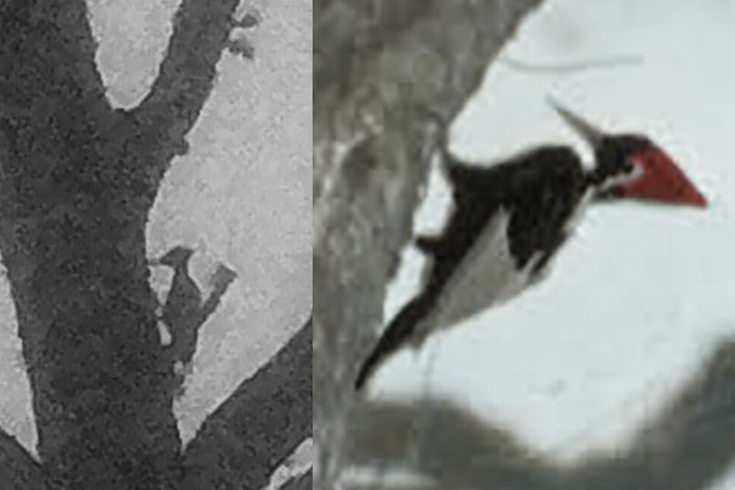

Biologists at the National Aviary in Pittsburgh contend that the photo on the left, taken in Louisiana, is an ivory-billed woodpecker, a species the U.S. government claims is extinct. The image on the right is a colorized photo from 1935, when the bird was still documented in Louisiana.

The ivory-billed woodpecker once flourished in the southeastern region of the United States, revered by bird watchers as the "Lord God Bird," until hunting and habitat loss depleted populations. Is the species extinct, as many have come to believe, or does it still exist?

Researchers at the National Aviary in Pittsburgh now say they have solid, living proof that the red-crested woodpecker survives in a swampy, bottomland forest in Louisiana. A peer-reviewed study published last week in the journal Ecology and Evolution lays out a decade's worth of research including photographs, audio files and drone videos that may identify the species.

The search for evidence is part of an effort to stop the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service from declaring the species extinct. The agency moved to delist the ivory-billed woodpecker from the federal list of endangered species in 2021, prompting outcries from biologists who ardently claim there's evidence they're still around.

Ivory-billed woodpeckers historically lived in a region that stretched from the Carolinas to East Texas. They were aggressively hunted for their plumage and beaks, and as their numbers shrank, the species became an elusive, inspiring symbol for painters and musicians. Singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens' song "The Lord God Bird" references the woodpecker's heavenly nickname, which was given for its distinct calls among the tall trees they drilled.

The last verified, widely accepted sighting of the species in North America was in 1944 in an area near Tallulah, Louisiana, called the Singer Tract. Previously, a tiny population of about 22 birds had been documented in parts of Florida, South Carolina and Louisiana, the National Aviary's paper explains.

Over the last several decades, some 200 sightings have been reported by game wardens, field biologists, ornithologists and amateur bird watchers. Their accounts have included a variety of evidence such as feathers, photos and audio recordings, but no consensus has been reached about whether these observations meet the necessary standards of proof that the woodpecker is still out there.

Last July, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service extended its deadline on making a final decision regarding the status of the ivory-billed woodpecker. The agency invited researchers to present clear video and photographic evidence that could be interpreted as such by independent observers.

Steven Latta, the National Aviary's conservation director, told the Washington Post in December that he observed an ivory-billed woodpecker with his own eyes at the research group's secret site in Louisiana.

“I had the opportunity to see this bird, and I have some personal responsibility, some professional responsibility to convince others,” Latta said.

Some of the evidence collected in the peer-reviewed study has already been presented to the government. It remains unclear whether the National Aviary's findings will sway federal decision makers or form part of a broader body of research that staves off the delisting. The government's decision is expected this spring, unless it is delayed again for further public hearings and evidence submissions.

One of the challenges of proving the existence of a living ivory-billed woodpecker is that the species closely resembles the smaller pileated woodpecker — the inspiration for the famed Woody the Woodpecker, created by cartoonist Walter Lantz. Both species have red crests with black and white feathers that can be difficult to distinguish without seeing them up-close. And despite the promising photos, drone videos and recordings, there haven't been any dead specimens available to examine.

Ornithologists are divided about whether there is strong enough proof of the bird's current existence. Nothing has been presented that matches the pioneering work of zoologist James Tanner during the first half of the 20th century, when many feared the ivory-billed woodpecker was already extinct. Tanner traveled to the Singer Tract in Louisiana and got close-range photographs of one he named "Sonny Boy."

The fight to keep the ivory-billed woodpecker on the endangered species list is about more than its admirers' devotion to the bird's beauty. Preventing the species from being deemed extinct could protect bottomland swamps that serve as habitats to other species.

"We are encouraged and energized by what we have discovered and accomplished," the National Aviary's research team concluded in its study. "We are optimistic that technologies will continue to improve our outcomes, including documentation through environmental DNA and other physical evidence."