July 15, 2024

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Isaiah Zagar's mosaics can be seen throughout Philadelphia, but his popotillo paintings – collaborations with Mexican artist Luz Maria Salinas – have never been exhibited. They are in the Magic Gardens archives.

Isaiah Zagar, the prolific mosaic artist whose work adorns over 200 walls in Philadelphia, has a few trademarks. Stare at his pieces long enough and you'll see them: bright colors, fractured shapes, references to other artists and surrealist figures with extra heads or limbs.

All four of these motifs are visible in a crop of lesser-known art by Zagar and a collaborator, long hidden from the Philly sunshine. These pieces, tucked away in his Watkins Street studio in South Philly, are not formed from the broken glass and tiles that make up a typical Zagar mosaic, but the grass and beeswax that Mexican folk artists have been using for centuries.

Zagar and Luz Maria Salinas began making these pieces when the pair met in Mexico City in the 1990s. Salinas is a longtime practitioner of straw or popotillo painting, an art tradition that involves weaving dyed grasses into a sheet of beeswax to create striking images. The grasses, native to the lakes of Mexico City, are called popotillo.

Pieces like these would typically cycle through Philadelphia's Magic Gardens, the mosaicked museum on South Street that is Zagar's largest and best-known work. But the popotillo paintings are extremely fragile and sensitive to light, making their display virtually impossible in the indoor-outdoor, sun-dappled space. According to Allison Boyle, the events and marketing manager for Magic Gardens, the museum has only shown prints of them in the past — even though there are approximately 500 straw paintings in its collection.

The process for these pieces typically began with a black-and-white drawing that Zagar would sketch in Philadelphia. On his next visit to Mexico — Zagar and his wife Julia, both deeply inspired by Latin folk art, frequently traveled there — he would deliver the drawing to Salinas. She would then "translate" the piece into a popotillo painting, selecting the colors and patterns as she interpreted them. Over the course of a few months, she'd meticulously press the colored grasses into the wax with her fingernail, matching the lines of Zagar's sketch. When he returned to Mexico, Salinas would present him with the finished work.

"A lot of times he wouldn't even remember the drawings he gave her and be like, 'Oh, what a fun surprise!'" Boyle said.

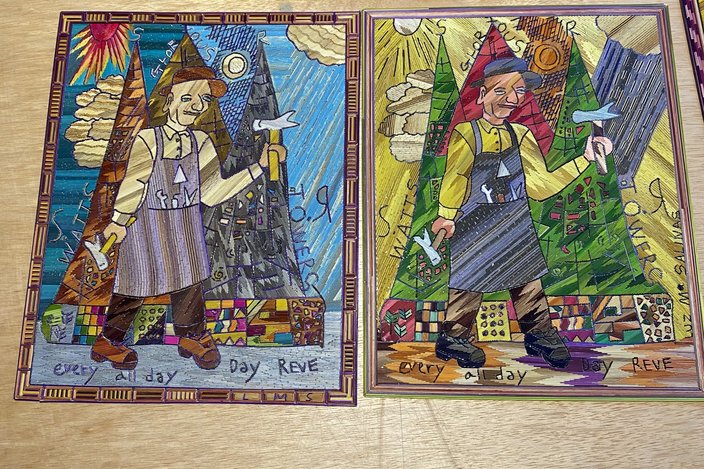

Salinas often made multiple versions of the same piece, spinning it a different way each time. An undated Zagar drawing of the artist Simon Rodia, for instance, generated two distinct paintings. In the first, Rodia stands in front of his famous Watts Towers in Los Angeles, the installations rendered in gray and brown to match the steel structures. The sky is blue, the sun a deep red with gold shading and Rodia himself appears somewhat pale in his neutrally-colored shirt, hat and apron.

But in another Salinas painting of the same drawing, a tanned Rodia is bathed in golden light. His towers looks more like Christmas trees in their green and red hues, and a torrent of dark rain pours from a cloud that was dry in the first version. The artist is dressed in the same clothes, but with jagged, quirkier patterns that extend to the ground below him.

Two interpretations of Isaiah Zagar's portrait of the artist Simon Rodia, who created the Watts Towers.

"I think he saw what she was doing and was really impressed with it," Boyle said about Zagar. "He works with a lot of different kinds of folk artists. Most of them are working three-dimensionally, you know, sculptures. But I think he just liked what she was doing. It's very unique, and she's very talented and doing something a little bit less traditional than maybe a lot of straw painters were doing."

The less traditional has always attracted Zagar, who often pays tribute to like-minded creatives in his own work. His popotillo collaborations with Salinas feature not just Rodia but Nek Chand, the late-Indian artist who created the mixed-media Rock Garden of Chandigarh (That collection of glass, ceramic and tiles is reminiscent of the Magic Gardens.) Zagar himself also appears in some of the pieces. In one, he and Julia hold a sun with a mustachioed face and tiny people poking out of its rays — a whimsical piece of folk art they would've bought in Mexico, Boyle said. In another, a pregnant Julia wears a wedding dress with the words "Painted Bride" written on her outfit, a nod to the former Old City art center covered with Zagar's work. She and Zagar dance with their cat Gato and deceased dog Blue.

Five of the popotillo paintings Luz Maria Salinas created from Isaiah Zagar drawings.

The future of the Magic Gardens and Zagar's legacy has been weighing heavily on the minds of museum staffers. The 85-year-old artist has slowed down in recent years, cutting back on the physically demanding work of making mosaics and his travel south of the border. To continue relationships with artists like Salinas, the Magic Gardens team has embarked on trips to Mexico since 2017. It has also had many, lengthy conversations with Zagar about his dreams for the museum. Turning the Watkins Street studio, which currently functions as the museum's archives, into a community space is one goal. Zagar would also like to see the Magic Gardens host more weddings.

"I hope we just keep going in his vision of being this space that's open to the public," Boyle said. "People can come in, get inspired. We'll continue to do tours, classes, things like that so people can learn not only about his work, but also mosaic art, folk art, art environments like this. I think we're just a really unique space in Philly and it's a really cool place for people to come learn about these things that they might have no idea about."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice