October 16, 2017

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Jason Edinger, a supervisor on the city health department's Vector Control Unit, pours poison into a rat burrow at Franklin Square Park in Old City. After one feeding, the rats bleed to death. Still, it's difficult to gain the upper hand on the rodents.

As children played on the swing set and jungle gym at Franklin Square on a recent warm Friday afternoon, Jason Edinger was looking for signs of rats.

There were droppings at the base of a street lamp, and a good-sized burrow dug into the dirt underneath an uprooted cement barrier, a few paces from the playground. Looking around, he pointed to all the amenities that make the Old City park such an attraction.

Not the Franklin Square Fountain, with its multi-colored sprays of water, the colorful carousel or the mini golf course that made the square an oasis in the center of Philadelphia. Those are for humans.

Instead, Edinger check-marked what attracts the dirty and disease-carrying rodents: low-hanging shrubbery to hide in, a steady water supply, and piles of garbage bags on the sidewalk, like the one yawning to reveal a bounty of discarded golden, soft baked goods.

“Rats are looking for three things,” said Edinger, a sanitation supervisor for the Philadelphia Health Department’s Vector Control Unit. “Food, water and shelter. As long as you give them a place to live and you provide the food and water for them, it’s going to be an unwanted pet that is never going to go away.”

Edinger, tall and lanky, is one of two supervisors for the 15-member Vector Control staff. It’s his job to go after vermin, including mosquitoes.

In January, Philadelphia made national headlines as having the most rat sightings of any U.S. city. According to the U.S. Census’ American Housing Survey, a little under 18 percent of the households in the region reported seeing a rat in 2015, the latest figures available. That’s more than New York, Boston, Chicago, Houston or Los Angeles.

The report, however, casts Philadelphia in a somewhat unfair light, city health officials say. The census captured rat sightings outside the city proper as well, including Camden and Wilmington. They are skeptical that the city of Philadelphia alone, with its 1.5 million people, has more rats than New York City, with a population topping 8.5 million.

Still, they have no problem acknowledging that Philadelphia, like most major cities, especially on the East Coast, has a rat problem that’s not going away.

Franklin Square is just one of 52 problem sites in the city that requires weekly visits from city exterminators hoping to contain the problem. The other sites include the Art Museum area, Rittenhouse Square, 28th and Dauphin, B Street and Erie and West River Drive.

“Wherever a number of people congregate,” Edinger said.

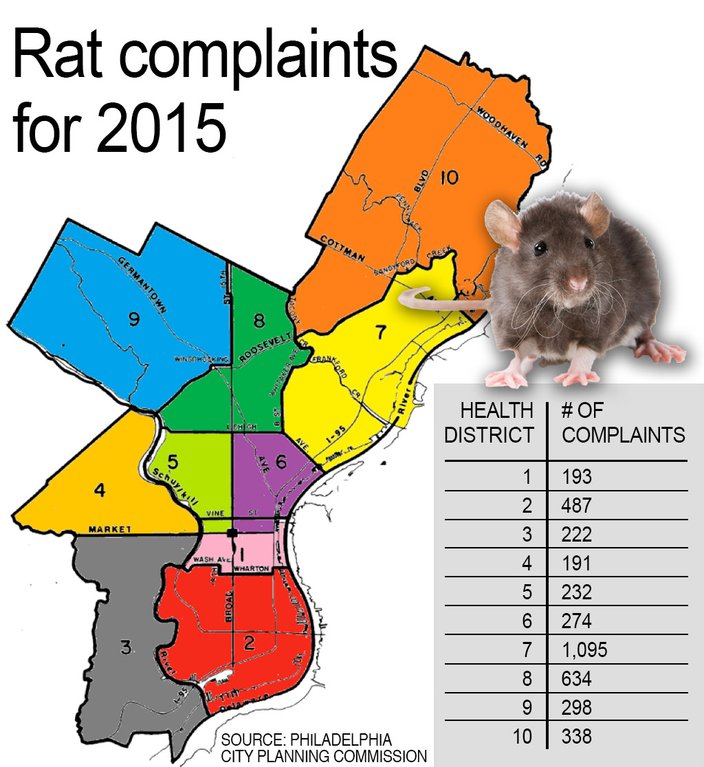

Rats have been reported in all 10 of the city’s health districts. But one district has far more reports than the others.

District 7, the oldest, most congested part of Philadelphia that includes an area east of Roosevelt Boulevard and 8th Street, between Lehigh Avenue and just north of Cottman Avenue, reported 1,095 rat sightings in 2015, 42 percent more than the 634 reports in next highest District 8, which sits just west of District 7.

District 4, a triangle of West Philadelphia bordered by the Schuykill River that is one of the smaller health districts, had the fewest rat sightings that year: 191.

But for many residents, even one sighting is too many.

The battle between man and rat has been a long-standing and fierce one, especially since rats spread disease and destroy property – they can chew their way through a home – not to mention the psychological fear they have on people. In Philadelphia, they go by different names: sewer rat, brown rat, city rat, Norway rat.

Eradicating them isn’t easy as it often involves changing people’s behavior about trash and rat poisons that can be deadly to pets and children … let alone lying spouses.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio earlier this year announced a $32 million rat eradication project for parts of Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. Chicago is experimenting with non-lethal dry ice as a means to suffocate rats in their burrows.

“This is an old city and a big city. You’re going to have rats.” – Jason Edinger, sanitation supervisor, Vector Control Unit

Philadelphia for its part is sticking with the classic technique: pouring poison deep inside a rat’s nest and letting them bleed to death.

The poison of choice: paraffinized pellets in 20-pound, black-and-yellow plastic containers. The sea green pellets contain bromadiolone, a potent rodenticide that prevents the body from recycling vitamin K, a necessary ingredient to create blood clots. It only takes one feeding.

Because of the health risks involved, pest control products containing bromadiolone are typically sold to professionals. The Vector Control Department tries to spread the pellets 12 inches below ground.

Philadelphia considered the use of dry ice, Edinger said, but it’s cost-prohibitive. The department, officials say, is already spending about $300 a week on dry ice during mosquito season to transport samples to state labs to test for West Nile flu.

.

Rats bring up a fear and loathing that few urban wild animals can equal. And they can be the stuff of legend.

Edinger has never seen a rat king, a collection of rodents attached to one another by the tail to form a withering mass of horror movie fright. But he’s heard plenty of slightly exaggerated or implausible stories from people who have either seen a rat or are trying to contain them: “They swear they were two feet long,” he said. “Truth is they can only get to a foot in length and that’s a large one.”

One mother, concerned that rats would climb up to the second floor of her home as they foraged, put food out on the first floor to appease them.

“She put food out right in the kitchen; they thought they were doing a good thing,” he said. “People just don’t know.”

Like most problems, prevention is the best solution. Keep food in tight containers. Bag your garbage. Pick up dog feces, which is food for rats. Block basement openings so they can’t get in. Call the department if you have a rat problem at 215-685-9000.

But when it’s too late for prevention, like in Franklin Park, it’s time for intervention.

Earlier in the week, Edinger’s team spread poison deep into the rat burrows and he wanted to check if the assault had worked. As an added precaution, he snaked a tube into the burrow he’d pointed out earlier and scooped a cup of pellets into the burrow, using a metal stick to pack them into the rodent shelter.

He knows it's a never-ending challenge.

“This is an old city and a big city,” he said, packing up his gear to leave the park. “You’re going to have rats.”

Later, PhillyVoice returned to the park, which by midnight was empty and quiet save for the swish of automatic sprinklers watering the grass and foliage.

The bags of garbage that would have presented a bounty to the rats were still on the sidewalk, waiting for pickup. They were all tied up.

But none showed any signs that a rat had come calling.

Score this a win, for now.

./.

./.