August 20, 2015

Photo courtesy/Amanda Schoonover

Photo courtesy/Amanda Schoonover

“I’m basically the American dream: I’m able to do the thing I love, get paid for it and own my own house,” said Amanda Schoonover, seen at right with Carla Belver in Act II Playhouse's production of "The Glass Menagerie." Schoonover has been acting in the city since 1992.

No one ever claimed that making a living as an actor is easy.

But with the Fringe Festival just around the corner – some of the most important weeks in Philadelphia theater – it’s worth looking at the economics of making it as an actor in this city.

As in so many things, it is tempting to contrast the experience of actors here to their counterparts in New York. Philadelphia stands out in two major ways. The local culture and labor pool incentivizes even the smallest of productions to pay their actors. The compensation is often just a pittance, but it can make a difference for those struggling to scrape rent together – an act that is also simplified by the dramatically lower cost of living in a city. Cheaper housing costs, in particular, make it easier for newcomers to stay the course and for some older actors to settle down, especially now that there are an abundance of theaters that have contracts with the principal stage actors union, the Actors' Equity Association.

“You can live in Philadelphia, own your home, have your family. If you are working for one of the bigger theaters, you can do theater at night, make a decent living and be at home by 11 o’clock having a beer on your porch.” – Philly actor Tom McCarthy

“I’m basically the American dream: I’m able to do the thing I love, get paid for it and own my own house,” said Amanda Schoonover, who has been acting in the city since 1992. She derives most of her income from acting or from other jobs where she can put her skills to use.

“I don’t know if you can do that in many other places," she said. "I don’t know that you can do that in New York City, even if you are on Broadway. I might never become a celebrity or something, but I feel pretty lucky to be here.”

The scene has changed dramatically in the past few decades, as Philadelphia evolved from a second-rate regional theater scene that hemorrhaged talent to one with a gravitational pull of its own. For much of the latter half of the 20th century, most of the primary roles in the city’s plays were taken by actors from New York, while locals would fill out some of the supporting cast and the bit parts. To make a career in theater, you had to leave Philadelphia.

One big problem, back then, was that only a handful of theaters enjoyed relations with Equity. If a theater did not have a union contract, then members could not work there. To get the best jobs in New York, and elsewhere, it is necessary to join the union. So without those contracts, Philly was doomed to remain a backwater.

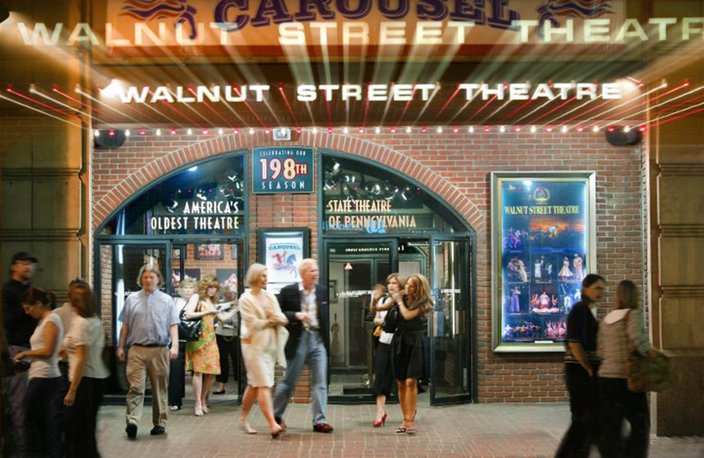

“Thirty years ago there was [almost] no theater in Philadelphia where an Equity actor could work – Walnut Street Theatre was one, there might have been two more,” said actor Tom McCarthy, a Philadelphia theater veteran of 50 years. “The artistic directors and business managers of the theaters got together with Equity and that was the big turning point. The actors who stayed in Philly, we fought with Equity to get into negotiations with the theaters so we could come up with a contract the theaters could afford.”

A 1989 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer describes the beginning of this process, reporting 15 Equity theaters in the metro region — up from exactly one in 1979. But when Schoonover arrived in 1992 she recalled that theaters with Equity contracts were still relatively hard to find. Today, at least 30 of 77 theaters in the Philly area have an Equity contract (that number doesn’t count venues that have special appearances by, or guest artist agreements with, Equity actors). The pay scale varies dramatically, from more than $900 a week minimum for the mammoth Walnut Street Theatre, to $776 minimum for the next tier (like the Arden or the Philadelphia Theatre Company) and a $618 minimum for the tier below that (the Wilma, for instance).

But these are the top theaters in the city. What about those just starting out or those who prefer to work in more avant garde theaters? Even for this strata, Philly holds an allure beyond the relatively low price of rent. Here, it is a norm to pay actors on the smaller stages, or even for readings. Partly, this may be due to the eligibility criteria for the local Barrymore Awards – think of them as Philly’s Tony Awards – which require applicants to offer actors a pay scale of at least $150 a week.

“The difference comes in the smaller theaters that aren’t required to pay us [by Equity] but still do,” said Krista Apple, who has worked in theater for 15 years, moving to Philly in 2006 for Temple’s theater program. “There seems to be more of a tradition here of compensating artists for their time. The smaller theaters here are paying their actors even though they don’t have to because if they don’t, actors will go take another show that will pay them. That is not the case as much in Chicago and New York.”

The difference may simply be that the supply of labor in Philadelphia is tighter. Actors showing up for an audition in New York will have far more competition from others of similar weight, height and temperament, so even getting an unpaid gig is tougher.

Despite Philly’s tradition of actually compensating its actors, few can get by on theater jobs alone. (For one thing, there are relatively few actors who can expect a steady string of stage work all throughout the year, so many will have to suffer at least a few weeks of unemployment.) Other than the universal side work of artists everywhere – bars, coffee shops and restaurants – Philly also offers theater work, of a kind, at the Constitution Center or as a standardized patient for the area’s many medical schools (which have a constant demand for people who can act like they really do have an incipient case of yellow fever or some rare strain of syphilis). The city’s many universities also offer plentiful adjunct work in theater departments, although the pay for those positions is almost as poor as acting. Combine working as an adjunct with acting and one's yearly income could hover around $30,000.

Still, there are presumably more homeowning actors in Philadelphia than New York. And because of the abundance of Equity theaters, and the relatively tight labor supply, good Philly actors can also be guaranteed relatively steady employment under the stage lights year-round, without having to leave the city. That is not the case in the Big Apple, where many actors are forced to take out-of-town gigs, or non-paying shows, due to the immense amount of competition.

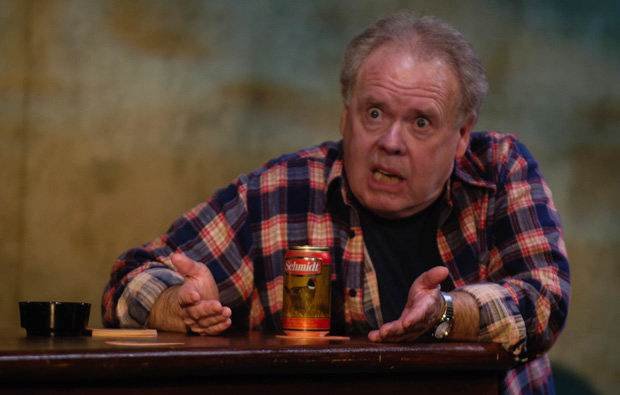

“There are thousands of actors living in New York City who probably never work in New York City; they have to go out in the road and all,” said McCarthy, who is turning 80 this year and estimated he has worked at almost every theater in Philly. “You can live in Philadelphia, own your home, have your family. If you are working for one of the bigger theaters, you can do theater at night, make a decent living and be at home by 11 o’clock having a beer on your porch.”