August 10, 2016

Courtesy of Susan Hindman/Jon Dorenbos family

Courtesy of Susan Hindman/Jon Dorenbos family

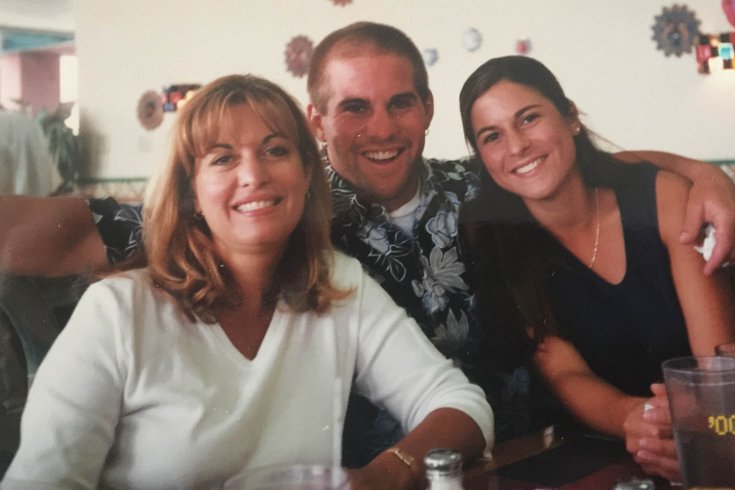

John Dorenbos his flanked by his aunt Susan Hindman, left, and his sister Kristina.

The time is fragmented in his mind. There are the little pieces here and there that he can paste together, though not much. Jon Dorenbos squints up at the sun after a recent Eagles practice, because after all of these years, that time — when he looked down at his shuffling feet, gripped by a nervous tension and fear of even looking up — has become hazy and dull. It was a time when he summoned the courage to peer through the inch-thick Plexiglas at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary, in Washington, separating his big, brown doe eyes from the cold, black stare belonging to his mother’s killer.

Dorenbos tried to suppress the nauseating emotion that was stirring within him. Everything that he believed in was gone. Everything that once made him feel safe was gone. There was confusion. There was disbelief. There was betrayal. There was a visceral gut-tug hurt.

It was then that the Eagles’ long-snapper, then a 12-year-old whose idyllic world was shattered at the time, erupted. He called his father, Alan, who murdered his mother, every nasty thing his young mind could think of. It was an explosion that lasted minutes, though it felt like hours.

And then, that was it. Closure. It was the last time Jon ever saw his father in person.

In a sense, a feeling of overwhelming relief took over. It wasn’t much of a feeling — but it was a start. The numb boy who placed himself in a bubble burst it open himself. That beginning spawned another beginning, an outlet where he could escape his cruel reality and disappear into a world he created: His world of magic.

On August 30, there will be over 10 million viewers across the country tuning in to see the Eagles’ veteran perform another of his impossible-to-believe, sleight-of-hand tricks during the semifinal round of “America’s Got Talent.” He won’t feel the pressure of their glare, or that of judges Simon Cowell or Heidi Klum, or the live audience he’ll be performing before.

They think he’s there to entertain them.

Dorenbos will already have them fooled.

Because in his mind there will be just one in the crowd, invisible to everyone but him. The one who actually never saw him render a room speechless with one of his ruses — his mother Kathy, who on August 2, 1992, was killed by her husband, Alan. The elder Dorenbos was released from prison after serving 11 years of a 13-year, eight-month sentence for second-degree murder.

Jon has always found refuge through his magic. It’s been the great healing elixir. It’s helped Dorenbos cope with the passing years, each a little easier to endure than the next.

“There’s not a day that goes by when I don’t think of my mother,” Jon says. “What happened to my mom was 24 years ago, and I’d be lying if I said it doesn’t still hurt. I wish she could see all the good things I’m doing now. I think that’s what hurts the most. But you also have to heal and time — and my magic — have helped me get through it. You never really get through it. I see my mom all the time and everywhere. It’s how I choose to live.

“I’ve been very fortunate. I have two great careers that I love. But I never wanted either one to define me. I’m passionate about football and I’m passionate about magic. Both have saved my life. I don’t know where I would be without football, and I definitely don’t know where I would be without magic. I have a lot of fun doing both and it’s a great balance. The fact that I’m able to do what I love to do is really all I wanted. Whenever my time comes, I want to die happy. The two things I love doing have made me happy, but it’s also important to me that it makes a lot of people happy — especially kids.”

In a sense, Dorenbos was robbed of his childhood.

He had every right to be angry. He had every right to despise the world. Someone murdered his mother, and that someone happened to be his father. So in one Sunday afternoon, in a span of 15 minutes, he lost both parents. He peeked at his mother’s autopsy photos and then closed his eyes.

Intense therapy aided him and older sister, Kristina, in coming to terms with their stark reality.

There were the times he went out by himself and screamed until his throat was hoarse. And the plenty of times he locked himself in his room to escape, honing his magic tricks.

What needed to be done first, however, was face what happened. Dorenbos made national news when, at 12, he and his older brother, Randy, then 17, testified against their father during his trial.

Joseph Santoliquito/for PhillyVoice

Joseph Santoliquito/for PhillyVoiceJon Dorenbos has played in 149 straight regular season games for the Eagles, third all-time behind Harold Carmichael (162) and Randy Logan (159).

“I know it’s human nature to do that, and I know I’m not perfect. I make a lot of mistakes. People soak in their own misery. I like the story of Nelson Mandela, when he was locked up for years. He gets all of the prisoners together and says, ‘They may have locked us up physically, but we will not let them take our souls. For if we let them take our souls, that’s when we truly become prisoners.’ They would sing songs to each other, and find ways to keep each other happy. Get rid of the hate and live free. I try to live by that.”

There are a number of heroes in Dorenbos’ story. There is his aunt, Susan Hindman, who took Jon and Kristina in when she was 32. She rearranged her life around them.

It’s why Jon made sure to point her out to the national audience on “America’s Got Talent.” Susan is Kathy’s younger sister and she gets emotional every time she sees him perform.

She was living in Garden Grove, California, and was a print broker when she got the call her sister was murdered. She collapsed as soon as she heard. It was Susan who introduced Jon to her friend, Ken Sands, who is a professional magician.

“Jon just turned 12 and Krissy was just going to turn 15,” Hindman recalled. “You just go into this mode of shock, when nothing seems real around you. I had to get myself up to Washington, where Jon was. Krissy was with my mother at the time they called us about Kathy. You have to keep going forward, and now I had Krissy and Jon who were parentless.

“Jon was 12 and he was being pulled in all of these different directions. I had to put up a strong front. I tried not to let them see me cry. I took the time at night when no one was around to let go of my emotions. Jon was asked to grow up fast. I always say he’s an old soul. He had to sit there and look his father in the eye during a murder trial.

“Thank God Jon found magic. I still have a problem with how Kathy lived those last few minutes of her life. That will never go away. But I look at the both of them today and it’s amazing. So yes, I get emotional every time I think about them — and how proud Kathy would be today. It’s why it hurts.”

That’s when Hindman had to break away for a moment.

Jon and Krissy became her priority. They call her “mom.” She calls them a miracle.

Randy, meanwhile, opted to stay with family friends in Woodinville, Washington, to finish high school. Today, Jon has very little contact with his older brother.

A major part of Dorenbos’ resonating, incomprehensible narrative is Krissy. She, too, could have taken a destructive path, as do many children that survive tragic, violent acts.

She didn’t.

Her success mirrors her younger brother’s. In many ways, she exceeds it. Today, Krissy Dorenbos, now Kristina Simeone, is a Ph.D. at Creighton University, in Omaha, Nebraska. She is one of the country’s leading researchers on epilepsy and how a special high-fat regiment, called the ketogenic diet and is effective in controlling seizures in patients who don’t respond to currently available medications.

“There’s no way I am where I am without my mom Susan and my sister,” Jon says. “Krissy was like a sister and a mother to me growing up. Anything I needed, I knew I could go to her and my aunt. Now look at all of the things she’s doing with her research and with children. My aunt and Krissy are amazing. My sister reminds me so much of my mom.

“You know something, how strange this might sound, I don’t hate my dad. I want nothing to do with him, but I don’t hate him. I forgive him. It took me some time to come around to that way of thinking. But I won’t think like he did. I got all of that hate out the day I confronted him in prison. I started to heal then.”

Krissy plans on being there for Jon’s next act on August 30. She admits it will be tough saying goodbye to her sons, who are 7 and 5.

“Jon is my inspiration, and he’s everything to my sons,” says Krissy, who resembles her mother. “I look at what we’re both doing today, and I don’t know if it was a conscious decision or not to do what we’re doing. But I find it interesting that what we both do involves children. Every aspect of Jon’s life makes him my hero. I can’t wait to be there for his next act. I’m going to be more nervous watching him than he will be performing.

“He never lets anyone down. I do love my little brother. Oh, sorry, my younger brother. What can you say about someone who cares as much he does about putting smiles on kids’ faces? That’s all he’ll see the next time he’s on AGT. He’ll see how happy he makes kids, and I know he makes our mother happy.”