February 24, 2022

Courtesy of/Temple University Health System

Courtesy of/Temple University Health System

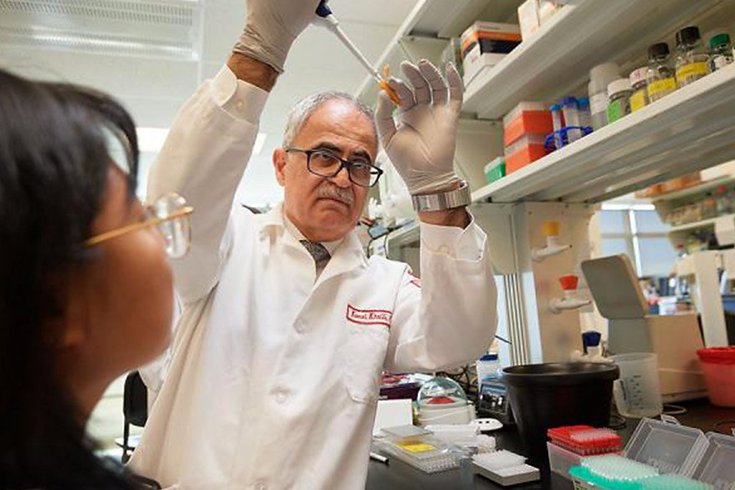

A clinical trial for a potentially curative gene-editing treatment for HIV is now underway. Kamel Khalili, a microbiologist at Temple University, above, is at the center of the research.

A team of Temple University scientists have started a clinical trial to test the safety and efficacy of a promising cure for human immunodeficiency virus.

The treatment, which is based on breakthrough CRISPR technology, uses gene-editing to to eradicate the genetic material of HIV from infected cells.

Previous research, conducted by Kamel Khalili and other microbiologists at Temple's Katz School of Medicine, has demonstrated the therapy's potential through experiments involving human cells and cells of humanized mice.

Khalili is the co-founder of Excision BioTherapeutics, which will conduct and oversee the clinical trial on the treatment, known formally as EBT-101. The organization received $60 million to fund the trial. Temple is not one of the sites that will be hosting it.

"Our research here at Temple created the foundation in part needed for Excision to initiate the clinical trial," said Tricia Burdo, associate professor of microbiology at Temple, whose research demonstrated the effectiveness of the gene-editing treatment on mice. "It is exciting now to see the research moving forward in humans."

Participants in the clinical trial will receive the treatment as a single, intravenous infusion to test its effectiveness as a one-time, curative treatment for HIV. The trial will be one of the first to attempt to extract HIV-infected DNA from the body.

Finding a cure for HIV has been difficult in part due to the intense, unique way the virus interacts within DNA. Shortly after infection, the virus intwines its genetic code into immune cells that do not actively replicate, meaning they are not impacted by antiretroviral treatments.

This gene-editing therapy could be curative because of its ability to remove HIV-infected DNA from parts of the cells that serve as "HIV reservoirs," Temple scientists say.

Because the virus can hide from popular antiretroviral treatments in these reservoirs, finding a method to overcome that has been difficult.

CRISPR gene-editing technology allows scientists to modify DNA in humans, animals and plants.

The technology is groundbreaking in its ability to alter plants to make them more tolerant to drought and other potentially damaging climate conditions. It also recently has been used to alter the DNA of a patient with sickle-cell disease.

The search for a cure to HIV has been decades in the making. On Feb. 15, scientists from Weill Cornell's leukemia program announced that a New York woman had been cured of HIV by using a stem cell treatment.

The woman was diagnosed with HIV in 2013, and used antiretroviral drugs to keep her viral status low. In 2017, she was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, also known as AML.

That August, the woman received cord blood from a donor whose mutation blocks HIV from entering into cells. In addition, the woman received partially-matched stem cells from a relative.

After two years, the woman shows no signs of HIV on blood tests. She joined three other people who have been essentially cured of HIV through breakthrough treatments.

In January, Moderna initiated a clinical trial for an HIV vaccine, a promising development that has been decades in the making. Previous attempts at developing an HIV vaccine have proven ineffective given the unique ways that HIV mutates in the human body. Moderna's vaccine uses mRNA technology, which the company has used for its COVID-19 vaccine.