In an episode from Season 7 of AMC's award-winning show “Mad Men,” protagonist and ad man Don Draper walks into the office, confused by the rows of empty desks and offices. A phone hangs off the hook, seemingly dropped mid-call. Where did everyone go?

Upstairs, he finds the entire agency crowded into the middle of the room, murmuring excitedly about the company's latest acquisition — not a new client account, but a giant computer. The heads of Sterling Cooper & Partners, clad in hard hats, announce to the crowd that the agency has “entered the future” with their purchase, which requires its own enormous, climate-controlled room.

- This is the latest installment in a PhillyVoice.com series called “The Science of Everything,” an opportunity for science journalist Meeri Kim, Ph.D., to explore the how and why of everyday things.

This period drama, set in the 1960s and '70s, gives us an insider look into the world of advertising in a vastly different era. Even back then, technological changes were afoot — television commercials saw growing popularity, and like the fictional Sterling Cooper & Partners, more agencies were investing in

their own computers. Now, with the addition of the Internet and smartphones, consumer metrics like ad clicks and product pageviews are more available for analysis than ever.

But the motivation behind advertising remains the same: get inside the head of potential buyers, find out what they are thinking, and use that knowledge to help persuade them to choose your product. Over the last decade, some companies and research groups are shifting toward neuroscience tactics like brain imaging to study why consumers behave the way they do. Others are exploring subtle new ways to influence buyers outside of using sight and sound, instead targeting their sense of smell.

“We're trying to understand how consumers make decisions and figure out the best ways to design commercials to better appeal to them,” said

Angelika Dimoka, biomedical engineer and director of Temple University's

Center for Neural Decision Making at the Fox School of Business. “Is there a neurophysiological measure to see which commercial would be more successful?”

Around the time of “Mad Men,” researchers largely used focus groups, multiple-choice tests, and other types of self-reported surveys as tools to peer into consumers' minds. Now, with the advancement of medical technology, they have a number of monitoring devices at their disposal: from simple biometrics like heart rate and respiration monitors to measure emotional responses, to electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that can directly record brain activity.

Dr. Paul A. Pavlou, Dr. Angelika Dimoka and Dr. Vinod Venkatraman of Temple University's Center for Neural Decision Making at the Fox School of Business. (Credit: Temple University Photography)

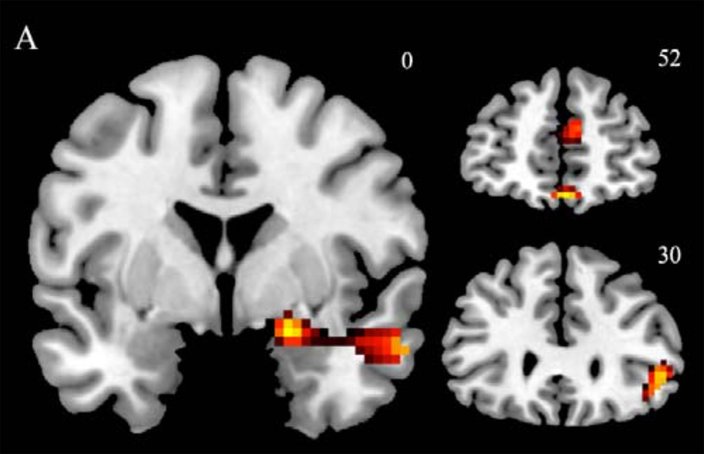

Using these tools, Dimoka and her colleagues study the neurobiological bases of human behavior, personal preferences, and decision making. In their experiments, one particular region of the brain has stood out. Activation seen in the ventral striatum, a key part of the brain's reward circuit,

can predict whether or not a commercial works — in fact, it has double the prediction value of traditional self-reported measures.

“When we anticipate a reward, when we feel rewarded, or when we would like a reward, this is the brain area that gets activated,” Dimoka said. “This brain area is connected with a desire to acquire something.”

Because of this link, the ventral striatum can be used to estimate willingness to pay for products. Activation in other areas of the brain, like the amygdala and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, have been found to convey how likable the ad was and whether a subject was actively paying attention to it.

In a study from 2014, Dimoka and her colleagues in collaboration with Time Warner Medialab showed subjects that year's Super Bowl commercials while measuring their biometrics and fMRI responses. They found brands that opted to tug on heartstrings kept their viewers more engaged than other, non-emotional ads. One front-runner was Budweiser's

“Puppy Love” spot, featuring a cross-species friendship between a puppy and the beer's iconic Clydesdale horse, which also became a viral video with more than 57 million views on YouTube.

In their subjects, the video elicited increased brain activity in regions associated with emotion, memory formation, and reward.

“If all these areas have been activated, that will be a commercial that the subject will also tell us they like it the most,” she said.

Compare that against a generally disliked commercial from

WeatherTech, a manufacturer of rubber floor mats for cars. The 30-second ad featured a number of businesspeople saying “You can't do that!” in response to ideas like building a factory in America, using American raw materials, and hiring American workers. Then a voiceover states that WeatherTech did all of the above.

“It was very, very boring. People didn't find it appealing, and none of those brain areas were activated,” Dimoka said. “Although when you asked people why they didn't like it, they couldn't really explain it.”

Activations in the brain that predicted the population-level popularity (liking) of the commercials used in the Temple University study. (Credit: Angelika Dimoka / Temple University)

Another researcher from Temple,

Maureen “Mimi” Morrin, is exploring innovative new ways to influence consumer purchases — by using their sense of smell. As a professor of marketing and supply chain management, she has spent the last 15 years working on scent research. Her latest study suggests that warm scents, like cinnamon and vanilla, can nudge people to buy more luxury items in a store.

Originally, advertisers and marketers assumed that an appealing scent would put consumers in a good mood, making them see a product in a rosier light than they ordinarily would. But Morrin says that isn't really how it works in practice. The effects of scent aren't based on happy versus sad as much as other emotions, she has found. For instance, some evoke feelings of warmth or cold, as in her most recent experiment.

“If over time you're exposed to something with a minty odor, then you experience that as being cold,” Morrin said. “Other odors like vanilla or cinnamon, people associate with warmth.”

When a warm scent was pumped into a store, more than just the sensation of temperature was affected. It made people feel like the room was smaller, more crowded, and that they had less personal space. The opposite was true for a mint or eucalyptus smell.

For the study,

published online January in the Journal of Marketing, different ambient scents were released into a retail store that sold sunglasses and prescription glasses in an urban shopping area. A warm, cinnamon scent was used for 11 days as Morrin and her colleagues recorded sales data such as brands purchased, number of items bought per transaction, and total dollar amount spent per transaction. After a day of no smell to let the cinnamon odor fully dissipate, a peppermint scent was brought in for the next 11 days.

Customers shopping while the store was scented with cinnamon bought significantly more items, with a higher proportion of them from luxury brands, than those in the peppermint-scented condition.

But why would this be? What is it about warm smells that makes us more likely to buy more and buy expensive? Through a handful of other experiments, the researchers untangled the reasoning behind this behavior that consumers themselves don't even realize.

Here goes: cinnamon and vanilla scents make us feel warmer, which lead us to feel a bit more claustrophobic and powerless. That, in turn, makes us act out in power-grabbing ways, like dropping more money for luxury items or spending more on multiple products in a single transaction in an attempt to up our social status.

“When we're in a small environment, we feel a little less powerful because we're constricted,” Morrin said. “We're motivated to restore our sense of power, and that manifests as a higher preference for luxury brands or premium products.”

Scent research has been intriguing to the industry because it represents a new way for manufacturers to establish their brands. Take Westin Hotels, which had a company develop a

proprietary white tea scent for them to use in their lobbies, spas, and toiletries. Whether you are aware of it or not, the company has found a way for us to associate their hotel chain with this particular pleasant odor — a tactic more corporations are starting to use.

We as consumers are bombarded with so much visual and auditory stimuli that we have become adept at specifically ignoring these types of ads. But as long as technology continues to advance, companies will always find new and innovative ways — like scanning our brains to tease out our true thoughts or wooing our sense of smell — to sway buyers.