March 16, 2018

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

A sign hanging in the reconstructed President's House at Independence National Historical Park tells the story of Oney Judge, a slave who escaped from George Washington while living in Philadelphia.

Nearly 222 years ago, Oney Judge slipped out of President George Washington's house in Philadelphia and fled to New Hampshire, a sudden disappearance that shocked the first family.

As a personal slave to Martha Washington, Judge had been given multiple sets of nice clothes, possibly even slept in her own room and was treated to social events – treatment most slaves did not receive, according to historians.

But Judge decided they were not worth her freedom. And she never regretted her decision to run away, despite living an impoverished life in New England.

"Through her own courageous actions she chose to defy the president of the United States ... when she was a young woman, and secure her own freedom," said Jed Levin, chief historian at Independence National Historical Park.

"It's an amazing story which allows us a glimpse into the life of one enslaved person in some detail, which is rare. Most of the people in Ona's situation are just names to us, if even that."

Her story mostly went untold outside of New England until about 10 years ago, when the President's House was reconstructed at Sixth and Market streets, near the Liberty Bell Center.

That site – where Presidents Washington and John Adams once lived – highlights the stories of Washington's slaves, who also lived there.

But it's a story that the historians at Independence National Historical Park say not only deserves greater recognition, but exemplifies women's history month.

"It's an amazing story," Levin said. "It's almost unbelievable in its poignancy, what it says about the time and what it says about who we are as a nation, today even."

Oney Judge was born into slavery several years before the American Revolution. Her mother, Betty Davis, served a seamstress for the Washingtons at their Mount Vernon plantation. Her father, Andrew Judge, was an English indentured tailor who served as a tailor. But because her mother was enslaved, Judge, by law, became a slave, too.

At age 10, she began serving as a personal maid to Martha Washington at the Virginia mansion. But when Washington became president in 1789, Judge lived with them in both New York City and Philadelphia.

The Washingtons believed they treated Judge as a daughter, Independence NPS historian Coxey Toogood said. Yet, they were set to give her to their granddaughter as a wedding present.

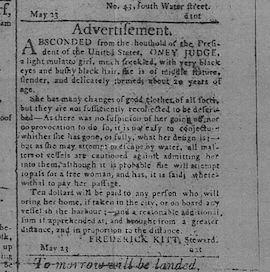

An advertisement that ran in the Pennsylvania Gazette on May 24, 1796 sought the return of Oney Judge to President George Washington.

Knowing this information, Judge decided to flee. But she did not do so impulsively. She gathered her belongings, including her clothes, transporting them to a sympathetic member of Philadelphia's free black community.

As the Washingtons went to dinner on May 21, 1796, Judge escaped to a sympathizer and waited to be smuggled onboard a ship sailing to Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Judge spoke openly with reporters later in her life, but never revealed who helped her escape.

Richard Allen, a former slave who bought his freedom, is known to have helped many slaves flee bondage, Toogood said. He also ran a successful chimney-sweep business, and worked on Washington's chimney in Philadelphia.

"It's always been an intriguing thing that he happened to be there that spring," Toogood said.

But it could have been any number of people. Philadelphia had a sizeable free black community from which an abolitionist movement eventually emerged. At the time of her escape, the community had established various churches, benevolent organizations and businesses.

"It was basically the roots of what later came to be called the underground railroad," said Levin. The term railroad, as we know it today, was decades away from common usage at the time, "but it was that kind of informal institution, people banding together to help their fellow human beings escape from bondage."

The reconstructed house where George Washington and John Adams lived as presidents in Philadelphia memorializes the stories of Washington's slaves, including Oney Judge.

Judge's escape caught the Washingtons completely off-guard. And they wanted her back.

"The Washingtons were shocked that she would seek her freedom," Levin said. "They thought that she was treated well. They couldn't conceive that being given away as a wedding present didn't comport with treating somebody well. In their view, she was treated well and there had to be some other reason why she ran away."

The Washington family placed an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, the prominent Colonial newspaper printed in Philadelphia, offering a $10 reward for her return. It noted that she had several sets of nice clothes, but they could not recollect what any of them looked like.

"She was there everyday, but they lived in different worlds," Levin said. "They didn't see her enough to describe any of her clothes. And they had a real motivation for describing those clothes."

At the time, Pennsylvania was in the middle of an enlongated process of becoming slave-free, thanks to Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, a complex 1780 law that grandfathered out slavery.

The law permitted non-residents to hold slaves in Pennsylvania for six months at a time, prompting non-residents to rotate their slaves. The bill was later amended to close that loophole, but Washington continued to engage in the practice without penalty.

"It's extraordinary that we know so much about Ona. It's because of her connection to the presidential household, but it's most immediately because of the abolition movement...." – Jed Levin, chief historian, Independence National Historical Park

And he skirted the law in his attempts to get Judge back, too.

Though Judge had fled some 350 miles away, she was recognized by a friend of the Washington family as she walked along the street.

As president, Washington had signed the first Fugitive Slave Act, creating a legal procedure for runaway slaves. But it required slaveholders to go through a magistrate, which Washington did not wish to do, fearing it could damage his reputation.

Instead, Washington privately attempted to have Judge captured and returned by using his government connections. Joseph Whipple – the Portsmouth collector of customs – refused to do so, fearing a riot at the hands of New Hampshire's abolitionists.

But Whipple informed Washington that he had met with Judge, who offered to return to the Washingtons under the condition that she be set free following their deaths.

The president refused, asserting Judge was bargaining and ungrateful.

"Washington also felt very strongly that he detected a complete thirst for freedom," Toogood said. "That changed his thinking about what she was really about. She was not lured away by a Frenchman, (as he previously had believed). She was really wanting her freedom."

Two years later, the Washingtons had virtually given up on retreiving Judge, who had married a sailor named Jack Staines and given birth to the first of their three children. But they made one last attempt through their nephew, Burwell Bassett, who had traveled to Portsmouth on business.

After failing to convince Judge to return to the Washingtons, Bassett informed Sen. John Langdon of his plans to capture her. But Langdon tipped off Judge, thwarting the attempt.

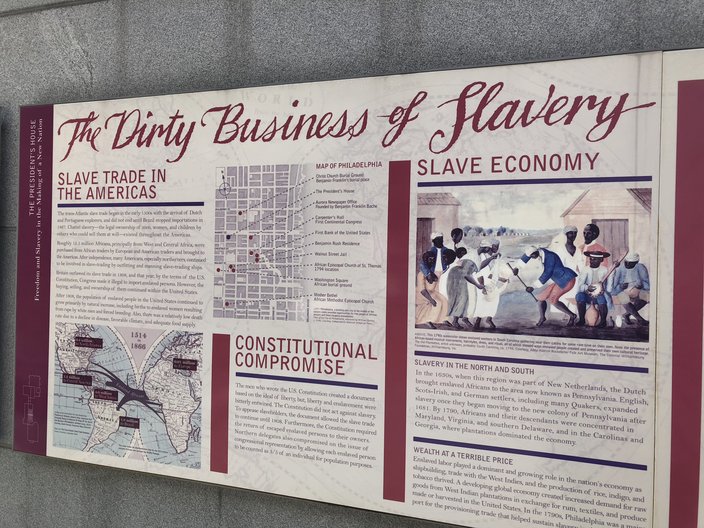

A sign hanging in the new President's House at Independence National Historical Park tells the horrors of the slave trade.

George Washington died in 1799. His will directed his slaves be freed upon Martha's death. But Martha opted to free them herself in 1801, before she died in May 1802.

Yet, Judge legally remained a fugitive slave until her death in 1848.

That's because she technically was never owned by the Washingtons. Judge had been among a group of slaves held by the estate of Martha Washington's first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. Upon her death, they were to be divided among the Custis heirs.

But as the anti-slavery movement gained momentum, Judge granted interviews to reporters representing abolitionist newspapers, describing the plight for her freedom.

"[Reporters] weren't trying to sully [Washington's] reputation – quite the contrary. To them, the Oney story was the most powerful argument for abolition that they could think of." – Jed Levin

"It's extraordinary that we know so much about Ona. It's because of her connection to the presidential household, but it's most immediately because of the abolition movement that was, even at that time, starting to develop and emerge at the time of her escape. But it certainly gained steam in the early 19th century."

Judge named John Bowles, the captain of the ship that carried her to freedom. But she never disclosed the people who helped her escape from the Washingtons.

"She just mentioned that people helped her, probably because she couldn't be sure all of them were dead and wouldn't be legally in jeopardy," Levin said.

Judge told the reporters that the Washingtons never taught her to read or write, nor did they give her a religious upbringing. She became a Christian and gained literacy after her freedom.

That Judge had been enslaved by Washington – a man considered to have an impeccable reputation – particularly interested the reporters, Levin said.

"They weren't trying to sully his reputation – quite the contrary," Levin said. "To them, the Oney story was the most powerful argument for abolition that they could think of. It showed how this evil institution reached so far to besmirch the reputation of a man who was otherwise viewed as having a stellar, almost sacred position of American iconography."

If a slave would flee from Washington, the abolitionists surmised, slavery could only be worse under others.

Judge, then living in poverty, affirmed their belief.

"She said she didn't regret running away because she lived out her life as a free woman," Levin said.

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice