May 06, 2020

Source/Contributed images

Source/Contributed images

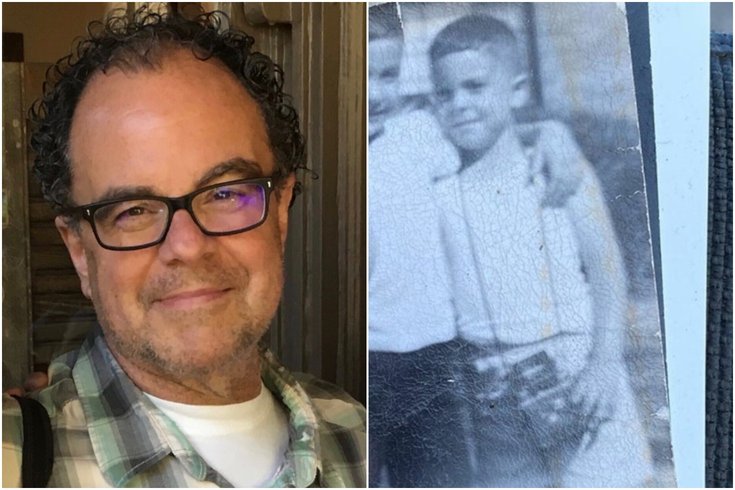

George Ross, a professional photographer and New Jersey native, died from COVID-19 in April. The image above shows him as an adult and as a child.

"Many people judge the importance of people by what they do in the world. George always made people feel important regardless of status or position," wrote Ellen Swandiak after learning of the death of her friend and colleague, photographer George Ross, of COVID-19.

Ross, a New Jersey native, was 60 years old. He built a successful career as a commercial photographer and had the creative eye of a fine artist. He died March 30.

Swandiak said Ross saw things differently, whether he was shooting interiors for IKEA and House Beautiful or sleek new designs from big names like Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Fifth Avenue. "To work with George was a dream," she said. "George worked with a sense of joy that stemmed from his deep love of photography and creative drive."

His other joy was his family. His younger brother, Bill Ross, executive director of TNG-CWA Local 38010 in Philly, remembers George as always having a camera around his neck. Growing up in a small town outside of Newark, Bill said that his big brother loved the arts. "He started doing silk-screening and photography early on," Bill said. "He even had his own dark room."

"I have always been attracted to the beauty of natural light. I love the craft and control of the studio, but am equally inspired by the random and surprising things one finds on location." – A quote from George Ross about photography

Bill's memories of his big brother are just as vivid as ever, like the time George let him tag along to a Kiss concert at Madison Square Garden when he was in fourth grade. George had made his own press pass and managed to get backstage to take shots of the band. He also sold T-shirts he silkscreened himself for a few bucks each in the parking lot. It was no surprise that George would end up attending the School of Visual Arts in New York, Bill said, where he truly honed his craft.

Children of divorce, the brothers were exceptionally close all their lives. A day didn't go by that they didn't text and call each other to share anecdotes about their lives and the news. Right before George ended up in the hospital, the brothers were texting about Trump being at Mar-a-Lago, shaking hands with world leaders despite this virus that was on everyone's mind.

Bill said when George starting getting sick, they were worried. Then things progressed so quickly. George went from feeling a little better to being intubated with no one at his bedside in North Jersey, which by then had become a second epicenter to the main outbreak in New York City. It was unfathomable.

"Honestly, we're numb still," Bill said. "The worst part was not being with him when he was sick." He credits the hospital staff for caring for George and everyone suffering from the coronavirus – they were incredibly kind under such tremendous pressure, Bill said.

When George was first admitted to the hospital, Katie Ross, his 28-year-old daughter who lives in Providence, Rhode Island, became the conduit of information, updating family and friends about her Dad, and calling the hospital several times a day.

For a time, George's health actually started to improve. "His oxygen levels were really good," said Katie. And then it happened so suddenly. In a matter of hours, he was intubated and then he was gone.

George's story is not unlike the stories of many thousands of COVID-19 patients around the United States. That's why George's loved ones are trying to find ways to remember their father, their brother, partner and friend in life rather than death. And at a time when grieving has evolved into an intensely complex and lonely experience in isolation, Katie said she's taking comfort in what an important presence her father had always been in her life.

"He always made me feel really smart and talented," she said. "A lot of his talent in seeing things and his photographs came from being gentle. He had a very gentle and respectful way of approaching everything."

It wasn't unusual for George to drive to Providence to meet Katie for an impromptu lunch. He was the type of guy who maintained and really nurtured relationships. After hearing of his death, Bill said a classmate of his brother's from kindergarten called him. He learned that George always kept in touch with people he had met throughout his life, no matter how busy he got working in the high-pressure commercial art world.

"He was an amazing editor ... He taught me everything. He taught me how to look at things."

– Katie Ross about her father

He was always his daughter's teacher and friend. He and Katie would regularly send work they were doing back and forth. "We talked on the phone once or twice a day," said Katie, who is also an artist. "He was an amazing editor. He would look at 400 images and cut them down to the best five. He taught me everything. He taught me how to look at things."

When Katie was just a kid, maybe 4 or 5 years old, "I had urgently asked him to come into my room to see how the light was hitting the wall." She remembered thinking it was so beautiful how George excitedly rushed to see it, with a childlike impatience. Her Dad was so proud.

Last week, she was working on an art project after he died and found herself using materials he had given her and thinking about him intensely. "My whole body of work is about ancestral learning," Katie said. "There's always a part of him in that."

For Cathy Schwing, George's longtime partner in business and life, his death is a loss on two levels – both personal and professional. The two had been working on several projects right up until he was hospitalized. It had been that way ever since they met in the 1980s.

"We grew up in the industry working together," she said. Just recently they were in New York City at an event at a design showroom before they both got sick. But as she started feeling better, George felt worse. "We had another project coming up," Cathy said, making the suddenness of George's death seem almost surreal. From the time he was first coughing until they heard the news, only a few short weeks had passed.

"We have no idea how we were exposed," Cathy said. "We were protecting ourselves early on when no one was really doing it. You just don't know how you're going to be vulnerable."

Source/Contributed image

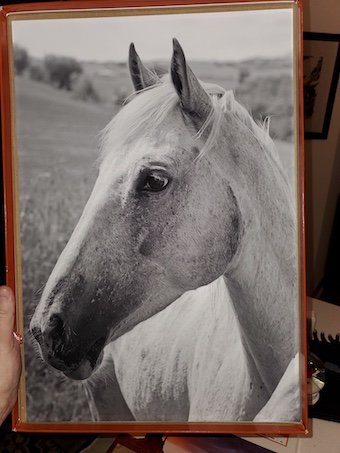

Source/Contributed imageGeorge Ross took this photo of a horse in Italy and gave it to his brother Bill Ross as a gift. 'Having his photos around me makes me feel good ... I look at it through George's eyes,' Bill says.

The hardest days now are the ones Cathy spends alone in the home they shared outside of New York City. "I wanted to take him to Northern Michigan when he felt better," she said. "He was the kindest man. He was someone who always listened; he never judged you."

Today, the dining table at the couple's home is filled with projects George was working on. She hasn't moved them yet. "He would wake up in the middle of the night to work," Cathy said. "He never stopped. And he always brought his camera with him."

His brother Bill finds himself spending a lot of time these days studying the photographs that George gave him over the years. "This past Thanksgiving he showed me a photo he had taken in Italy of a white horse alone in a field," he said. Bill loved it, so for Christmas, George printed and framed it for him. "Having his photos around me makes me feel good," Bill said. "I look at this horse in the morning when I get up and when I go to bed. I look at it through George's eyes."

Bill hopes that when it's safe to be together again, that family and friends can gather to celebrate his brother's life. Since before and even after George died, the coronavirus has prevented them from grieving together, which has been a challenge for so many families during this pandemic.

Katie said she's actually relieved that the world is on pause because of the pandemic and she's not expected to go about as usual.

"I'm really grateful I don't have to go back to work next week. I don't have to put a deadline on this grieving process," she said. "It's not normal. And you don't have to be normal."