October 18, 2017

Source/Hawthorne Books

Source/Hawthorne Books

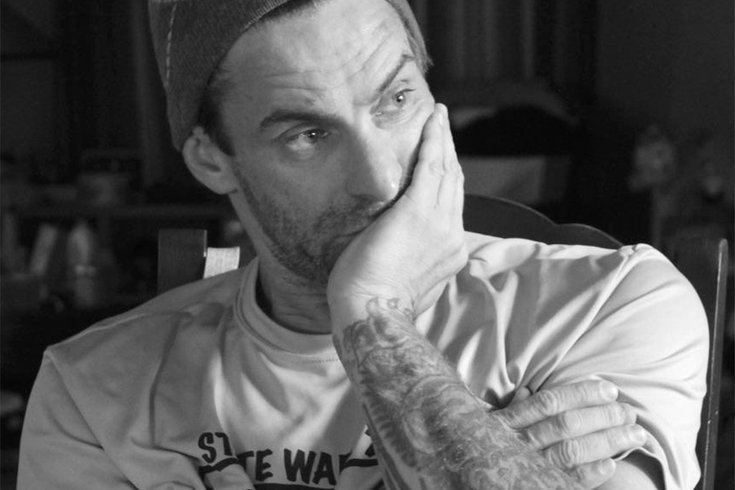

Frank Meeink's violent childhood in South Philadelphia primed him to hate and led to his descent into America’s Nazi underground. By the time he was 16, he was one of the most notorious skinhead gang leaders on the East Coast. Two years later, he was doing hard time in an Illinois prison.

Frank Meeink remembers rolling into a Lancaster nightclub with one primary purpose: picking a fight with a group of skaters during a concert.

He was 14 years old and his childhood had been anything but easy. But the South Philadelphia native finally had found acceptance – with a group of skinheads.

A fight indeed broke out during the concert, with Meeink safely perched atop the shoulders of a larger skinhead. Yet, he realized their power when his group verbally threatened another skater as they left the venue.

"I saw the look on his face and I absolutely loved it," Meeink said. "... It felt good to see someone have fear of me. That night, someone asked if I wanted to be a part of it, and I f***ing jumped at it."

Soon, Meeink was hating more than skaters.

Meeink quickly ascended the ranks of the neo-Nazi world, even hosting a cable access talk show, "The Reich," on television. But within three years, he was a teenager serving time in an adult prison in Illinois.

Once again, his world began to change – a bit more slowly. He began questioning his white supremacist ideology, eventually abandoning his fellow neo-Nazis not long after being released from prison.

Today, Meeink serves as a vocal opponent of white supremacy, sharing his recovery story at speaking engagements across the country.

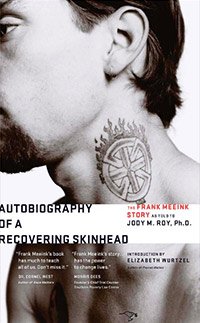

An updated version of his book, "Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead," was published last month by Hawthorne Books, adding an additional nine chapters to history. The new section details his struggles with addiction, his friendships with celebrities and the deaths of his son and mother.

The new edition of the book includes a preface by the author, nine new chapters, an updated epilogue, and advice for substance abuse recovery and countering racism.

"I end the book saying, 'I don't know what's going to happen,'" Meeink said. "I just know that it's been a long journey and the book is what I've learned."

But Meeink said he'll never return to a lifestyle based on hate.

"Racism is the greatest bait-and-switch ever pulled in the world," Meeink said. "It's a legendary bait-and-switch. It's done on such a horrendous scale. It's something you have no control of – it's your skin."

White supremacy provides its believers acceptance, a feeling coveted by most of the ideology's recruits, Meeink said. But that acceptance comes at a tremendous cost.

Meeink remembers a conversation he once had with Tony McAleer, a former recruiter for the White Aryan Resistance with whom he co-founded Life After Hate, a nonprofit that helps individuals who want to leave a lifestyle of hatred and violence.

"'Frank, we didn't lose our humanity when we joined this group,'" Meeink recalled McAleer saying. "'We just gave it up for acceptance.'"

Meeink was introduced to white supremacy when he moved out to the Lancaster area to live with his cousin, who helped him assimilate into a group of neo-Nazis.

And it came at a moment when he was craving acceptance.

His childhood in South Philly had been difficult. His mother mostly raised him on her own until age 9, when she remarried a man whom Meeink says often tried to "beat the Italian out of me."

"I can't say, 'Abracadabra, I'm not the neo-Nazi whisperer here. I'm just a guy who can relate to a guy who has gone down that path." – Frank Meeink, former Philadelphia skinhead

At 13, Meeink moved in with his dad in Southwest Philadelphia, where he attended a mostly-black middle school. He routinely engaged in fights.

Meeink finally found people who took an interest in his life when he went to live with his cousin.

He accompanied the skinheads to Bible studies, where they'd share ideology. Beforehand, they'd shoot guns together.

Most importantly, the skinheads inquired about his life in Philly.

"They couldn't fathom that I had seen black people all the time," Meeink said. "To me, it was someone asking me, 'How is my life?'"

Finally feeling accepted, Meeink eventually bought into their ideology.

He soon was traveling across the country, recruiting others to join the neo-Nazi movement and espousing his views on television. He rolled with neo-Nazi groups notorious for their violence.

"It changed everything in me," Meeink said. "I grew up a huge Philadelphia Flyers fan, a huge Philadelphia Eagles fan. I could tell you who their draft picks were up until 1988. After 1988, until 1994, I can't tell you who was on the team. This became my life."

One Christmas Eve, Meeink and an accomplice kidnapped a rival skinhead at gunpoint in Springfield, Illinois and spent the evening beating him – all while recording it on videotape. The victim informed the police and, soon enough, Meeink was serving three years in an adult correctional facility.

But that experience provided the seeds for change.

During prison recess, Meeink began playing football with a group of black inmates who welcomed him into their crowd – despite his swastika tattoo.

"Right now, one of their guys is in the White House. They feel empowered by this, definitely." – Frank Meeink

"They let me be a kickoff returner on the first play," Meeink said. "I knew no one was going to block for me. I ran that ball back for a touchdown. After that, they let me play."

And bonds began to form.

"After we were done playing sports with the guys, you talk," Meeink said. "You talk about home life. You talk about girls. I just enjoyed my time with them. ... They were city kids like me."

Upon his prison release, Meeink initially returned to his neo-Nazi crowd in Philadelphia. But a number of experiences, including his time in prison, prompted him to leave.

A Jewish man in Fox Chase not only had given him a job as a furniture assemblyman, but he had treated Meeink with respect. He began cross-referencing his stereotypes with the realities he saw in his life.

But it was empathy that broke him, Meeink said. And it holds the power to do that to others, too.

Today, when he's talking to someone struggling to overcome his or her hateful ideology, that's the tool he uses.

"I can't say, 'Abracadabra,'" Meeink said. "I'm not the neo-Nazi whisperer here. I'm just a guy who can relate to a guy who has gone down that path."

For Meeink, the path to advocacy began with the Oklahoma City bombing, carried out by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols in April 1995.

The explosion at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building killed 168 people. Afterward, investigators found excerpts of "The Turner Diaries" in McVeigh's getaway car. The novel, by neo-Nazi William Pierce, describes the bombing of the FBI headquarters with a homemade bomb.

The bombing struck a nerve.

"That whole event tore me up inside," Meeink said. "When I saw the pictures of that dead little girl in the firefighter's arms, it made me go from a guy in South Philly who was hiding from his past to an activist."

Meeink first went to the FBI – not because he had anything to report, but because he knew they would understand his past. The FBI pointed him to the Anti-Defamation League, which kickstarted the speaking engagements he has continued to this day.

"You can't just not do bad s*** and think you should get a cookie for that," Meeink said. "I started thinking, 'I'm always going to do something positive.'"

Meeink partnered with the Flyers to launch Hockey Through Harmony, a hate prevention program, and later developed a similar program in Des Moines, Iowa, where he now lives.

He also helped launch Life After Hate, where he speaks with people grappling with the same hatred he once fostered.

White supremacist groups have gained headlines across the United States during the last year, most prominently during a rally in Charlottesville that left three people dead, including Heather Heyer, who was killed when a car crashed into a crowd of protesters.

Meeink is blunt when addressing the state of white supremacy in America.

"Right now, one of their guys is in the White House," Meeink said. "They feel empowered by this, definitely. "

White supremacist groups also surged after Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, Meeink said. But they lost their momentum when Obama didn't take the myriad actions white supremacists claimed he would. But Trump's campaign awakened them.

Now, many white supremacists groups are identifying as "Alt-Right," an uber-form of conservatism.

"They always have to rebrand themselves from the groups that are before them, because they did really bad s***," Meeink said. "These guys have to change the script a little bit. They have to say, 'We're not the same guys.'

"They're fearful, scared males. It's the same group."

That fear prompts them to resort to violence, as seen in Charlottesville, Meeink said.

"Because you're full of fear, that's what happens," Meeink said. "They lash out violently. What else are you going to get out of the situation?"

That's where Meeink preaches empathy.

Violence by leftist groups won't halt the hateful rhetoric spewed by white supremacists, Meeink said. Nor will accusations.

Instead, Meeink said, it takes someone to show them the love and empathy they seek. And it helps when it comes from someone like him, who once shared the same identity.

"I'm going to tell them why they believe that way," Meeink said. "Here's the truth to that. Or here's the turning point."

It's what led him out of white supremacism. And he's convinced it's the best tool for leading others out, too.

Source/Hawthorne Books

Source/Hawthorne Books