March 10, 2016

Penn athletics/for PhillyVoice

Penn athletics/for PhillyVoice

Head coach Jack McCloskey leads the celebration after Penn defeated Princeton to clinch their first official Ivy League title.

Jack McCloskey’s voice trails off as he begins to recall the 1965-66 University of Pennsylvania men’s basketball team.

“Oh, boy…” said the former Penn head coach.

McCloskey is 90 years old and doesn’t remember every detail of the historic season that happened 50 years ago, but his competitive passion comes through as he recalls with pride and also frustration his final year at Penn.

“My career was very good, but it never surpassed the depth of what happened,” said McCloskey who eventually became general manager of the two-time NBA champion Detroit Pistons after leaving Penn at the end of that year. “I could never forget that.”

The 1966 season concluded with the Quakers’ first official Ivy League championship but the luster of that accomplishment was tarnished by an injustice never before nor since repeated in Ivy history. Penn went 19-6 overall and 12-2 in the Ivies, but was ruled ineligible to compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association tournament when it would not agree to comply with the NCAA’s new academic standard requiring certification of a 1.6 minimum grade point average for all student-athletes, equivalent to a C-minus. So Penn, an Ivy League school, lost out on the chance to play in the NCAA tournament due to an academic argument.

“We weren’t even in the discussion,” said Stan Pawlak, co-captain along with Jeff Neuman of the 1966 team. “We were just pawns in the middle of this silly disagreement that the Ivy League was having with the NCAA. And the Ivy League was correct in the argument, but certainly their correctness didn’t have to be manifested in us not going.”

It was the NCAA’s first attempt to establish an academic baseline for scholarship schools. Even though it easily met that standard, Penn, which as an Ivy school did not give scholarships, repeatedly refused to certify that it met the standard.

“The Ivy League didn’t buy into the idea that the NCAA could dictate our eligibility standards,” Pawlak said. “You can understand why, but the fight didn’t have to get to the point it did.”

Pawlak, Neuman, John Hellings and Charly Fitzgerald – four seniors from 1966 (a fifth, Bob Auchter, passed away in 1984) – met Tuesday at McCloskey’s new home state of Georgia. It was their first chance in decades to reminisce about what happened.

“They’re bonded by it to this day,” said current Penn head coach Steve Donahue. “They were snubbed, and they’re connected maybe more than they would have been.

“It’s hard to imagine that happening this day and age. I feel bad for those guys. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and it was taken from them for really no good reason.”

***

The NCAA sent a telegram on March 4, 1966, initially allowing Penn to play in the tournament if it just would agree to certification, but a telegram in response from Penn’s then-Athletic Director Jeremiah Ford II reiterated Penn’s position of non-compliance. The NCAA then responded with the subsequent ban later in that day, even after McCloskey had gone to Ford’s office to make a last-ditch plea.

“His words were, the NCAA knows what Ivy League teams have,” McCloskey said. “He left it at that. At that moment, I had to hold myself back. I had to leave. I couldn’t stand the guy.”

University President Gaylord Harnwell Hon supported Ford’s decision to not comply with the new NCAA regulation as did the entire Ivy League, whose presidents shortly thereafter voted to withdraw from NCAA championship events that year. Not everyone sympathized with their stance. Dan Jenkins wrote in Sports Illustrated that “when the welfare of the entire collegiate community is considered, the Ivies, despite scattered good points and splendid intentions, are dead wrong.”

The Penn basketball team and some Yale University swimmers were the only Ivy athletes recorded as missing out on competing in NCAA championship competitions in 1966.

“You have to feel for those guys,” said former Princeton University Athletic Director Gary Walters, a point guard on the Princeton team that Penn beat to clinch the Ivy crown. “You had to feel for them that the league wasn’t represented. I also respect the fact that the presidents felt it an issue of such import that they acted in concert.”

Since the Ivy League began official play as an eight-team conference in 1956-57, the 1966 season remains the only one in which they have not sent a men’s basketball representative to the NCAA tournament.

“I remember distinctly, it was an academic thing that didn’t apply to them,” said Hall of Fame head coach Jim Boeheim of Syracuse University. “They didn’t have anyone that was a 1.6 GPA or even a 2.6, they were probably all 3.6.”

Boeheim was a senior starter for Syracuse in 1966. The Orange were supposed to play Penn in the first round of the NCAA tournament in Blacksburg, Va., but Syracuse was given a bye into the next round when Penn was ruled out.

“In today’s world, I think the entire basketball team would probably have been sitting on his desk,” Pawlak said of Ford. “We kind of put our tails between our legs and never said a word about it, which to this day, that makes me angrier than anything else. We know McCloskey made a huge fight to the point where he left his job that year, but Ford was just too strict and stern an individual to sacrifice his own ego so the kids could play.”

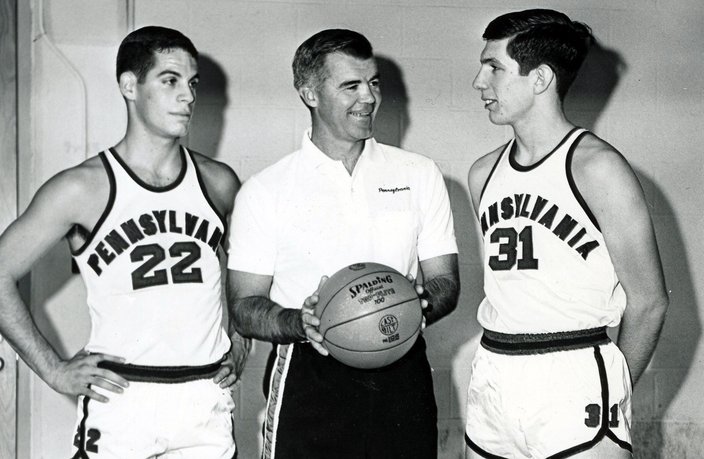

Co-captains and leading scorers Jeff Neuman' left, and Stan Pawlak bookend head coach Jack McCloskey.

“We had winning seasons throughout and competed throughout, and when it was our turn in my senior year when Bradley was gone, we did what we were supposed to do and took care of business,” Pawlak said. “We won the league. Princeton was not an easy out at that point. Cornell was very good, and Columbia was very good. There were four really good competitive teams in the league. To win it was a heck of an accomplishment.”

***

Penn wanted the chance to show how good it was on a national level. Instead McCloskey had to break the news to his players after a half-hearted practice that the Quakers were done.

“I remember going to practice, but it was kind of like a day in football where you don’t hit anyone,” Neuman said. “You lightly go about it because you wonder what is going on. There wasn’t intensity. There was a sense of pretty much doom.”

McCloskey, a Penn graduate who had coached his alma mater 10 seasons, had gone as far as to scout Syracuse against Niagara. He felt unsupported by the administration when he had to deliver the doomsday message.

“Oh, it was damaging,” he said. “I hated that and I hated leaving the University. I loved my school.”

McCloskey was also the baseball coach at Penn then, and he quit midway through the spring to move on to coach basketball at Wake Forest. He’d eventually go on to an immensely successful NBA career in 1979, but he never planned to leave Penn.

“I’d be there forever because I had a lot of friends there who I went to the University with,” McCloskey said. “They loved our team and respected it and respected the players that were on that team. That was a jolt (when he left).”

The potential first-round NCAA matchup in 1966 would have been an intriguing one. Led by Dave Bing, Syracuse topped the nation with a 99 points per game scoring average. Penn was seventh in the country in scoring defense at just under 63 points per game. After Syracuse beat Davidson, they went on to lose the regional final to Duke, and Duke lost to Kentucky who fell in the historic final to the first all-black starting five from Texas Western.

“Syracuse might have beat us by 40,” Pawlak said. “I think we would have played very well against them. I played several years in the Eastern League after college and I played against three of the kids that were on that team – certainly not Dave Bing, I’m not putting myself in a class with him – but Jim Boeheim was on that team. I played against Jim for many, many years. I always felt I could hold my own against anybody, and certainly Jeff could and our other players could.”

Penn owned a pair of Big Five victories, including a win over a Villanova team that would eventually finish third in the then-illustrious National Invitational Tournament. The Quakers had the same star guard power that is so valued in NCAA tournament play today, plus they had good size with three players 6-foot-8 or taller.

“Stan and I worked well together,” Neuman said. “He was very, very difficult to guard on defense without the ball. He’d get free and get a lot of backdoors. We knew each other’s instincts very well. We just played very well together. We ran a lot. It was fun.”

Neuman was drafted into the NBA but chose to attend Wharton a year later. Pawlak, the first Penn player inducted into the Big Five Hall of Fame, played six seasons in the Eastern Basketball Association.

Members of the 1966 Penn basketball team staged a reunion Tuesday at former coach Jack McCloskey's home in Georgia. From left to right: John Hellings, Charly Fitzgerald, Jeff Neuman, McCloskey and Stan Pawlak.

***

The conflict between the Ivy League and the NCAA was smoothed out by 1967 when Ivy champion Princeton went to the NCAA tournament.

“You talk to people today that are so avidly involved in the tournament today, and you tell this story, if you tell what happened to us, they can’t believe it,” Pawlak said. “That’s what makes me laugh. We accepted it way more easily than we should have back then.”

As time has gone by, Pawlak has thought back about how it ended with more pain. He has followed Penn closely through the years, and for more than a decade now has been a part of its radio play-by-play team.

“As time went on, and I continued to play, and I coached and continued to stay in the game, I think I’m angrier now than I was as a senior in college,” Pawlak said. “We were too naïve. We were naïve kids that didn’t know how to fight. We didn’t know how to fight for our own rights back then.”

Now 50 years later some are fighting to recognize the greatness and significance of that team. State Senator Stewart J. Greenleaf, a 1961 Penn graduate who played for McCloskey, is working on honoring his former coach and Penn’s first official Ivy championship team.

“They still talk about it,” Greenleaf said. “There’s still some pain there, some disappointment there. I thought it might be nice if we invited them to come to The Palestra and have the University of Penn and the NCAA to recognize them for their accomplishments.

“I have reached out to the University of Penn. They showed some interest. It hasn’t happened yet.”

Penn athletics/for PhillyVoice

Penn athletics/for PhillyVoice Courtesy of Stan Pawlak/for PhillyVoice

Courtesy of Stan Pawlak/for PhillyVoice