March 03, 2016

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

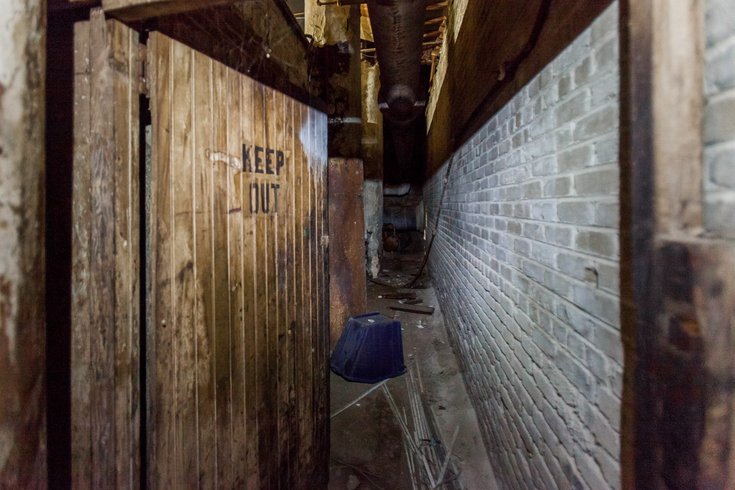

A door marked "Keep Out" leads to a massive vault under Jewelers Row.

On a cold Saturday in January, Grim Philly tour guide Joe Wojie regaled a group of tourists with tales of Christmas past during an afternoon Nightmare Before Christmas Tavern Tour.

The day was filled with stories of the origins of the Judeo-Christian holiday, but as a student of local history, Wojie shared a tale apparently well-known among those with a serious interest in Philadelphia history.

He teased tour patrons with speculation about tunnels under Jewelers Row that allegedly run from the Curtis Center at 7th and Walnut streets, to Chestnut Street, and then split – east to the Delaware River and west to City Hall.

"I used to think that these tunnels, if they exist at all, were figments of people's imaginations. Perhaps they are. But enough anecdotal evidence exists to say that there is something to the stories." – Harry Kyriakodis, Philadelphia historian

Miles of tunnels might have been used for smuggling slaves before the end of slavery, he said. And they were, he theorized, used during Prohibition to move hooch trucked into a parking garage under the Curtis Center into storage, until the illegal liquor could be distributed to speakeasies around the city.

These days, said Wojie, a Rider University professor, the tunnels can be only accessed by film crews for movie shoots – if they know who to ask for permission.

But do they even exist?

We went looking.

The idea of tunnels under Center City and Old City has long interested local historians.

Fishtown-based historian Ken Milano – author of several books on the history of Kensington, Fishtown and the river ward communities – said he'd heard the stories, but was never able to find concrete evidence of their existence."I've never seen any evidence, like been down in the cave, or tunnel, nor read it anywhere official," he said.

Harry Kyriakodis has heard the same talk.

A historian who has written extensively about Philadelphia's past, including books on Northern Liberties and the Philadelphia riverfront, he's never seen solid evidence of the tunnels. But that doesn't mean they don't exist, Kyriakodis said.

"I used to think that these tunnels, if they exist at all, were figments of people's imaginations," he wrote in an email. "Perhaps they are. But enough anecdotal evidence exists to say that there is something to the stories."

Next stop: Naomi Nelson.

The executive director of the American Women's Heritage Society Underground Railroad Museum at Belmont Mansion, Nelson was aware of talk that tunnels were possibly used for smuggling slaves into Philadelphia – or, conversely, for sneaking fugitive slaves to freedom via the Underground Railroad.

She never heard of any such tunnels used by slaves under Jeweler's Row, Chestnut Street or the Curtis Center, but said that we should reach out to Charles Blockson, a renowned historian and author who has an Afro-American collection named for him at Temple University. If there was any evidence of slave activity in any tunnels under Jeweler's Row or Chestnut Street, she said, he would know.

We needed to speak to Blockson by messages relayed through Aslaku Berhanu, a librarian at Temple University. And, after some correspondence, Blockson said there could be a nugget of truth to the tales, but he "has yet to prove with any documentary evidence that the story is real."

So, we kept looking.

Sean Bratton, property manager for the Curtis Center, walks the tunnel that runs from the Curtis Center to the Public Ledger Building across Sansom at 7th Street.

Some historians suggested we dig still deeper into the history of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia for evidence of these tunnels.

We contacted Vincent Fraley, communications manager at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, who was kind enough to share a copy of the journal of William Still.

Still, an African American and abolitionist who lived from 1821 to 1902, was a "conductor" on the Underground Railroad and was said to have kept track of most of the movement of refugee slaves heading north through Philadelphia to escape the bonds of slavery.

A transcripted version of Still's journal doesn't seem to mention tunnels under Jeweler's Row or the Curtis Center. But perhaps the journal is too specific.

Covering the years 1853-57, it mostly consists of long lists of names of refugees and detailed facts about them, such as their age, descriptions of their appearance, names of members of their families and tales of their travels through Philadelphia.

If there was some way to move slaves through tunnels in Philadelphia, Still had mentioned nothing.

Rochelle Christopher, historian and executive director of Victorian Vanities, a local non-profit that focuses on teaching American history, had a different idea.

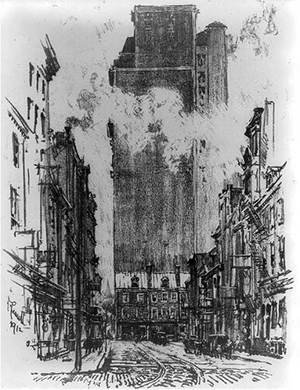

Down Sansom Street from Eighth Street, a 1914 lithograph by Joseph Pennell.

She suggested that, perhaps, these tunnels weren't tunnels at all, but instead vaults used by turn-of-the-century jewelers to protect their wares.

"If there's any tunnels, it's just going to be an abandoned subway tunnel," she suggested. "Who would have built them? Slaves? No, they had other work to do... And, it would be like digging through New York, where would you put all the dirt?"

Look at the "Sanborn maps," several historians told us.

The fire insurance maps, produced since 1866 by the Sanborn Map Company, detail building footprints, building material, building height, building use, lot lines, road widths and water facilities throughout Philadelphia, much of Pennsylvania and some of the nation's largest cities.

According to Marcel Basset, a spokesman for the Planning Commission, Sanborn updated its maps with paper mache overlays. Peeling off the overlays to go back in time far enough for evidence of the tunnels would destroy the more-than-a-century-old maps, according to Bassett, who said that would be "impossible."

A week later, Bassett was able to recover an old map – dating to 1939 – of the pedestrian concourse for the Market Street subway line. The map shows a tunnel running along 8th Street, from Market to Chestnut streets. That tunnel remains today, of course, giving pedestrians access to Race Street trolleys, the Market-Frankford Line and PATCO trains.

But with that tunnel dating back more than 75 years, it stoked our hopes for the rumored tunnels just a block or two away.

The rusted door that leads to a long-unused vault under a building on Jeweler's Row. Just beyond this door, the vault's roof had caved in.

With the help of Sean Bratton, property manager for Keystone Property Group, we can say for sure there is a tunnel under the Curtis Center. Keystone manages the building at 7th and Walnut streets, off Washington Square.

Whether it was used to move and store booze during Prohibition, Bratton wasn't sure. Leading the way into an underground parking garage under the building, he noted that building was owned by Cyrus Curtis, a publisher, in 1891. We ducked under some long-dormant steam pipes to a tunnel on the north side of the underground garage complex.

"There's a lot of interesting little nooks and crannies in this building," Bratton said.

The short tunnel leads directly under Sansom Street at 7th - evidenced by the footsteps and traffic above - to a large steel door that opened to the basement under the Public Ledger Building.

Curtis bought the Public Ledger building in 1913, and the buildings were likely connected so the copies of the newspaper, printed in the Public Ledger building, could be moved through the tunnel to delivery trucks waiting in the underground garage under the Curtis Center.

But we weren't done. We had to get below Jewelers Row to take a look for ourselves.

A steel door that closes off the tunnel under the Curtis Center that runs under Sansom Street.

It wasn't exactly easy, but we did – sort of.

With the help of one shop owner, we had the opportunity to go below Jewelers Row. (For reasons of safety and security, we promised not to divulge the exact location.)

In an enormous, wide-open underground space we could again hear the sounds of daily life on the streets above. Along the north wall, there were no signs of a tunnel – nothing in the concrete to indicate any changes over time.

The south wall was more interesting. The concrete had a gap at the top – about three feet wide – where the wall didn't meet the ceiling. A doorway had been cut out in the center of the wall.

Through the doorway, a narrow space ran the entirety of the wall. Squeezing in there, we used a ladder brought from the basement and our flashlights to look over the top of the wall – and set our eyes on a huge old vault.

Two enormous steel doors – open enough to squeeze through, but stiff with rust and etched with a floral design too worn to tell the maker's mark – led into the vault, once used by past Jewelers Row proprietors.

Kicking up so much brown-gray dust that it was hard to breathe, we tried to enter the vault. But, alas, the roof had caved in and rubble covered the area just beyond the vault doors.

In the dark corners of the vault we could see rubble, dirt and the remains of its most recent inhabitants – we saw dead rodents, in other words.

Ultimately, we came away with little solid evidence to suggest other underground tunnels.

From dead rats to a dead end, you might say. But we'll keep our eyes and ears open, and keep tunneling for the truth.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Source/Library of Congress

Source/Library of Congress Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice