Recently, researchers at the University of Geneva

published their findings on how chameleons differ from most other species in how they change the color of their skin.

While color-shifting animals generally have pigmented cells that can hide or reveal hues as the situation demands,

chameleons also possess two layers of light-reflective skin made up of cells containing crystals of various sizes. When chameleons make adjustments to these crystals, the color of their skin changes structurally from broad-spectrum light, similar to how the sky gets it blue color from light refraction.

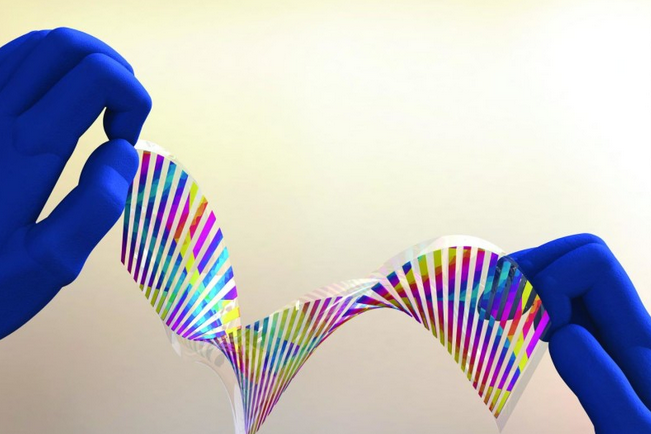

Engineers from the University of California at Berkeley applied similar principles of structural color to develop a

flexible material that changes color based on how light strikes it, ScienceDaily reports.

By etching ridges into a single, thin layer of silicon, the engineers created a material that can be "tuned" to interact with different wavelengths of light when its dimensions are changed.

"This is the first time anybody has made a flexible chameleon-like skin that can change color simply by flexing it," said Connie J. Chang-Hasnain, a member of the Berkeley team and co-author on a paper published today in Optica, The Optical Society's (OSA) new high-impact journal.

Working on a minuscule scale, the engineers formed their grafting bars using a semiconductor layer of silicon (just 120 nanometers thick) that can be embedded into a flexible layer of silicone. When bent, the spacing of the ridges enables the material to respond with sharp, precise variations in color.

While the material could have dazzling uses in displays, outdoor entertainment and even camouflage, it could also be used very practically as a sensor to indicate structural fatigue on bridges, buildings or the wings of airplanes.

The Optical Society /Via ScienceDaily

The Optical Society /Via ScienceDaily