The ER is busy. Nurses and doctors hustle from one patient to the next. There isn’t an empty room. In fact, even the makeshift rooms separated by thin curtain walls are full. On-the-go conversations, beeping machines, ringing phones, hurried footsteps and concerned faces surround me. As the chaplain on call, I move through the cacophonous afternoon guided both by formal visit requests and my intuition.

Between calls to respond to various traumas, I catch a glimpse of an elderly, frail woman slumped over in a chair. A hospital gown limply falls around the folds of her form. Surrounded by temporary cotton walls, she receives only a slight semblance of privacy. She is alone. The nearby machines beep steadily. I decide to visit her.

There’s no way to knock, as there is no door. I stand on one side of the lightly colored curtain, introduce myself, and ask to enter.

“Come in chaplain,” her curt voice startles me.

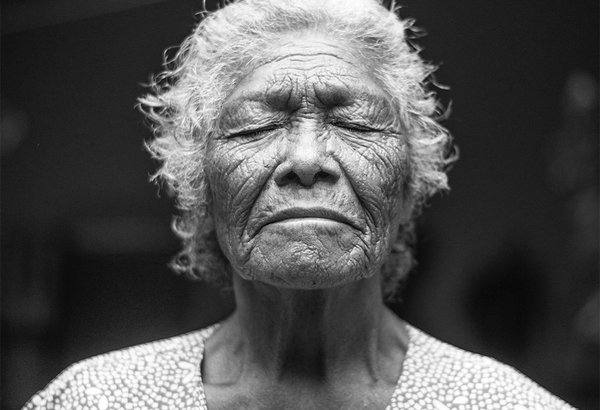

Stark white, limp hair frames a furrowed and ashen face. Her first name is Eileen. She welcomes my visit because she has something important to say.

“Listen,” she states as she motions for me to step closer. “Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Growing old is a bitch. You are forgotten. No one visits. No one cares.” Her face contorts with anger.

I kneel down so that I am at her eye level. “Tell me more,” I softy suggest.

Her voice rises, “No one cares I’m here. No one knows. My children have forgotten me. I am alone. Look at me! I am alone.”

Eileen’s emotional pain is visceral, her loneliness deep. I ask to hold her hand and she nods. Her hand is boney and cool to the touch. She looks at me with piercing eyes. “You don’t even care about me. It’s just your job to listen.”

I take a deep breath. I don’t turn away. “You are in a lot of pain. Growing old is so hard and you feel very alone,” I say this in my best attempt to mirror back to her the reality she describes. For a moment, the surrounding noises fade. She holds my hand and weeps bitter tears. A few minutes pass and then, my beeper goes off.

“I need to go Eileen, but I can check in with you later,” I tell her as she wipes her eyes.

“Don’t bother. I won’t be here long. Just remember what I’m telling you. Growing old is a bitch.” She spits as she speaks. Her wrinkled face is again flush with anger. “Remember me. I’m telling you the truth.”

I can’t forget.

Dignified care

In her March 2014 New York Times op-ed entitled “Emergency Rooms Are No Places for the Elderly,” Dr. Pauline W. Chen notes, “…it’s hard to imagine a health care setting more ill suited for the elderly than today’s emergency rooms.” Under pressure to quickly determine whether ER patients are to be admitted or discharged, the complex needs of the elderly are often overlooked. Whether an elderly patient arrives alone or with a devoted family member, a busy ER is not a friendly place for the aged.

Of course, Eileen’s loneliness and anger extended far beyond her hospital experience. Perhaps her children were myopically busy with their own lives and disconnected from the needs of their mother. It’s also possible that they were involved, despite her protestations otherwise. I wonder if Eileen’s own attitude and choices constituted the root of her suffering. I found her to be a sad, bitter, and lonely old woman. It’s possible that she would have been a sad, bitter, and lonely 40-year-old. Yet, experiencing the impersonal and rushed medical treatment of a busy ER could only amplify her pain. Even I had to end my pastoral care visit early to attend to an incoming trauma.

When caring for the elderly, “it is nearly impossible to work quickly,” Chen observes.

While Chen highlights a growing movement to change medical practices in order to provide the dignified care elderly deserve, the challenge of navigating the complexity of a single hospital visit constitutes only part of the struggle facing the aged in our culture.

Gone are the days when the majority of the elderly lived with their adult children. Today, only 16 percent of American households include an elderly member. Older Americans either live alone or in institutions designed to fit the needs of their complex medical profiles and accommodate the busy lives of their children. For those Americans who provide their elderly relatives with the necessary daily care, the economic consequences of this choice are significant. In a June 2011 study entitled, “Caregiving Costs to Working Caregivers,” MetLife Mature Market Institute estimates that, over a five-year span, the average female caregiver loses nearly $143,000 in wages due to leaving the labor force in order to care for an elderly parent at home. This figure includes estimated wages lost due to re-entering the workforce following a multi-year gap. When calculating the Social Security benefits lost during this time, the figure above doubles.

This matters. For the first time in human history, the majority of people in wealthy nations will live well into their 70s -- and often beyond. America is undergoing a demographic transition. In the report “Older Americans 2010: Key Indicators of Well-Being” compiled by 15 federal agencies, it is estimated that by 2030, 72 million Americans will be over 65 – that’s 20 percent of the overall population. Compare this to 1930, when older Americans constituted 5.4 percent of the population. As they advance in years, the powerful purse, active lifestyle, and intellectual energy characterizing the Baby Boomers will transform the way aging is seen in America. Will this demographic shift impact our vision of what constitutes beauty? Will this shift transform our sense of what matters most in a life well lived?

Most of us aspire to live lengthy, dignified, and meaningful lives. Living longer is an attainable norm for those in the developed world, leading to the overall aging of our global population. However, our ageist culture values efficiency, sequesters the elderly, glorifies youthful appearance, and emphasizes the acquisition of objects over the nurturance of relationships. These attitudes, and the practices based on them, must change if we are to fully realize our aspirations.

“Loyal to the face I’ve made”

In explaining why there is a lack of geriatric specialists despite the rapidly increasing number of elderly seeking health care, Dr. Ula Hwang states, “Older adults aren’t the kind of patients people gravitate toward.” Hwang, associate professor of emergency medicine, geriatrics, and palliative care at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai continues, “There’s a reason you don’t see the frail, cognitively and functionally impaired older patient on television medical shows.”

What if we were to gravitate to our elders -- especially those suffering from cognitive and functional impairments? What would we see? The shadow of our youth-worshipping, achievement- oriented culture is present in their last dance with time. Aging -- both in others and in ourselves -- reminds us of key truths obscured by the relentless consumption upon which our market-driven culture depends. In many ways, our vapid consumerism attempts to assuage our fear of aging and dying. Our own inevitable demise is reflected upon the wrinkled skin so often sequestered and ignored. What matters most is the love extended and received while living. Is it any wonder that the elderly are largely absent from the dominant discourse found in mainstream media whose purpose now exists primarily to sell products?

In fact, most television and film stars, as well as popular musicians, go to great lengths to camouflage and disguise their own aging. The majority of us follow suit. Worldwide, the anti-aging industry is valued at $261.9 billion according to a 2013 report issued by BCC Research in Wellesley, Mass. An entire school of surgery has developed to temporarily ward off the appearance of aging with skin lifting, cutting, and tucking precision. The desire to look 25, even if one is 60, reveals much more than a simple dislike for the aging process. As a culture, we fight aging as if it were a disease. It’s worth remembering that the billions spent each year on anti-aging paraphernalia and face-altering surgeries actually do nothing to stem the inevitable passage of time that transforms us as relentlessly as ocean tides transform the shore.

Film icon and beauty legend Marilyn Monroe once stated, “I want to grow old without facelifts. … I want to have the courage to be loyal to the face I've made. Sometimes I think it would be easier to avoid old age, to die young, but then you'd never complete your life, would you? You'd never wholly know you.” Monroe’s astute reflections stand in stark contrast to the reality of her final breaths. Imagine an alternative ending. Would she have grown old without facelifts? Would she have found the courage “to be loyal to the face” she had made? If so, would witnessing Monroe’s natural aging have changed our dominant model of what constitutes beauty?

Consider the case of a wealthy octogenarian who woos 20-year-old women with cash and escapades of luxurious adventure. He seeks counsel from the young men on his staff about dating “this new generation.” Through repeated facelifts, he attempts to ward off the imprint of his many years. One on hand, why shouldn’t this man use his riches to strive to live the life of a 30-year-old? Why should we judge his sexual engagement with young college-bound women, even if they are the age of his grandchildren? Given the inordinate amount of value placed in our culture on youthful sexuality and male virility, his interests make sense. Yet, one wonders how our collective phobia regarding aging fits in here. What would this man look like free of his numerous cosmetic surgeries? We’ll never know. Carefully hidden scars and repeatedly stretched skin constitute the face he has made.

Whether celebrated or abhorred, aging happens. With our rapidly aging demographic, American stands at a crossroads. On one hand, elderly Americans can buy into our dominant ageist paradigm. They can internalize a youth-worshipping preference and fiercely scorn their own body’s natural transformation. Given this scenario, profits will boom for the anti-aging industry. But what if we uprooted our collective fear of aging -- a fear that only fuels the sequestering and ignoring of our elders? It’s time we shift from an obsession with appearance and acquisition and learn to listen, connect, and honor the legacy our elders provide.

Leaving a Legacy

According to psychologist Robert Emmons, the majority of our human pursuits can be divided into four categories: achievement and work, intimacy and relationships, spirituality and religion, and “generativity” -- leaving a legacy or positive contribution to society. In summarizing Emmons work, Professor of Psychology Jonathan Haidt explains that those who pursue wealth and achievement are “less happy, on average, than those whose strivings focus on the other three categories.”

The elderly in particular, benefit from nurturing meaningful relationships, sustaining a spiritual and/or religious practice, and focusing upon leaving a legacy. Goals associated with work and achievement relate to earlier stages in life. In old age, the network of peer-relationships thins due to death, and nurturing a meaningful connection to younger generations takes precedence. Though often disregarded, our elderly long to share their hard-earned wisdom culled from decades of human experience.

Founded in 1991, the Philadelphia-based Bridging the Gaps program provides health-related services to disadvantaged communities by linking future social service and health providers to a wide-range of volunteer and internship opportunities. Christopher McGrath, a student at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, reflects upon the significance of his internship at the Philadelphia Senior Center (PSC). He states, “Working with the seniors at the PSC has encouraged me to let go of preconceptions and learn from a population whose abilities, wisdom and input often get overlooked.”

Haidt details the benefits of volunteer work, particularly for the elderly when it comes to nurturing the feelings of happiness and purposeful existence. In his book The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, Haidt writes, “The elderly benefit even more than do other adults, particularly when their volunteer work either involves direct person-to-person helping or is done through a religious organization.”

South Philadelphia native Fran Miller regards her retirement as a time for “restructuring” wherein she can nurture interests she didn’t have time for previously. Miller notes, “My eight grandchildren, ages 10 to 20, are getting older, and I’m not needed much.” Rather than brooding over this fact, Miller volunteers as a museum guide and currently serves on the Board of Directors for the Philadelphia Corporation for Aging. “I’ve always been interested in history and the arts, and I love to work with people. … We’re so fortunate to have great museums here. I try to instill in my grandchildren the love I have for culture and the arts.”

My grandfather is a 96-year-old Mormon widow, World War Two veteran, poet, dentist, father of seven, grandfather to 29, and great-grandfather to 48. He continues to live in his Kaysville, Utah, home purchased with my late-grandmother decades ago. He loves to garden, write poetry, and visit the gravesite of his beloved. For decades, he volunteered his time to serve The Latter Day Saint community in various leadership roles, even serving as bishop to a local ward.

Today, one of his seven children lives with him caring for his overall wellbeing as advanced age takes its physical and mental toll. He can no longer hear well and his memory fades with each passing day. The last time I saw my grandfather, he kept confusing me for my sister. Yet, my grandfather still picks away at his computer typing up poems in remembrance of yesteryears. Having served as a commanding officer leading infantry in ground combat in Italy, many of his poems highlight duty to God and country. My grandfather’s focus on the Mormon faith and his poetry help explain why he sustains an optimistic attitude toward life, even when he can’t remember which grandchild is visiting.

The Future

As I walk through the frozen food aisle in our local supermarket, my 3-year-old son’s toes playfully push into my thighs. It’s a game we play when he sits in a shopping cart. He smiles at me with each step. I notice an elderly woman on my right. I try to imagine what life was like when she was a toddler. She leans her deeply wrinkled arms onto her cart as she makes her way through her shopping list. The years of little toes pass quickly, as do our days with wrinkles.

I look again at my son and imagine life eighty years from now. Statistically, he has a good chance of being alive in 2094. Currently, life expectancy for US males is 76 -- eight years longer than it was for children born in 1970. However, time only has value when it is experienced as worthwhile. I pray that my son lives a long and meaningful life. While I won’t live to see wrinkles transform his skin, I hope he embraces their beauty with dignity. May he sidestep any temptation to pay a surgeon to cut his body and stretch away the face he’s made.

I remember Eileen. Hours following our conversation, I returned to the ER to check in on her but she had been discharged. It’s hard to imagine what ER rooms will be like a century from now. Perhaps advancements will inspire a restructuring of mainstream treatment modalities. Rather than placing inordinate emphasis on speed, technology, and machines, perhaps future generations will emphasize human connection and a holistic vision of wellbeing. Regardless, I pray my son is not alone when he, as an old man, visits the hospitals of the future. And if he is, may he carry in his heart gratitude rather than bitterness.

We stand at a crossroads. By 2030, one in five Americans will be over 65. We can choose to dignify the rhythms of birth, aging, and death inherently woven into the fabric of biology. Or, we can build elaborate and expensive fortresses of sand based upon the illusion that we can ward off the next inevitable wave of change moving through us. Either way, our choices form the attitude our children, and their children, will have when they look at our aging faces and, one day, into the mirror.