May 13, 2024

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

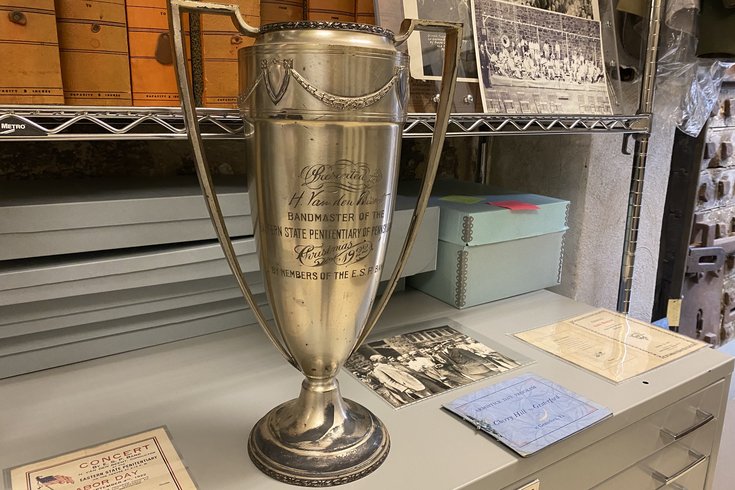

Eastern State Penitentiary acquired this silver trophy cup, originally presented to the prison's bandmaster Hedda van den Beemt, from his grandson. The ESP Band often had its music played on local radio.

The first record of a musical performance at Eastern State Penitentiary dates back to 1864, as Union and Confederate soldiers battled across the South in the waning days of the Civil War. The musicians came from the outside — a choir of young girls who performed at the prison — but the incarcerated men of the Fairmount prison soon began making their own melodies, which were broadcast far beyond their cellblocks.

From the early 20th century up until the prison's closure in 1971, the men imprisoned at Eastern State Penitentiary formed jazz and country bands, orchestras and choirs, penning original compositions and performing in holiday concerts broadcast on the radio. One of those bands was led by Hedda van den Beemt, a Dutch violinist who was also maestro for the University of Pennsylvania band and orchestra. A silver trophy cup he received from the ESP Band in 1922 is still in archives of the penitentiary, which became a museum in 1994. It stands as a unique memento from the programs that brought solace to thousands — and turned several first-time players into lauded musicians.

"I find music to be a very regular occurrence at Eastern State," said Damon McCool, senior manager of program development for the museum. "We have a series of records including a warden's daily journal, where they're documenting everything that's happening that day. I would say it was a weekly, if not more than once a week occurrence."

Band practices or performances weren't possible when the prison first opened in 1829. The 11-acre site was founded on the principle of "confinement in solitude with labor," which meant prisoners were separated day and night. (In the early days, guards even forced inmates to wear hoods whenever they left their cells.) Though solitary was considered a revolutionary model at the time, criticism grew over the decades — most notably from author Charles Dickens, who called the system "very cruel and severe" after a 1842 visit — and the practice was quietly and gradually abandoned. By 1890, half of the prisoners had cellmates.

This shift opened up the possibility of group performance. According to McCool, the first incarcerated musicians to play for their peers were a group of banjoists who worked in the kitchen. Music became "more sophisticated, more organized" as formal orchestras, choirs and other bands formed and the prison brought in outside experts to help.

One of those experts was van den Beemt. The musician had left the Netherlands to play first violin with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and he became heavily involved in the city's classical music scene. When he wasn't working at Penn, he was conducting for the Philadelphia Operatic Society, the Savoy Opera Company and the Frankford Symphony Orchestra. He was also the director of the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music until his sudden death from pneumonia in 1925.

Van den Beemt found that music had a positive impact on the members of the ESP Band, suggesting to an Evening Public Ledger reporter that "criminals respond genuinely to music, and that with every response the inclination to crime is being weakened." Its effect on morale, he continued, was undeniable.

"(There) is an aggravated and infectious mal de (vivre), during which the man declares that he feels it is worthless to go on," he said. "Always at such times I tell him that he need not play unless he chooses to, but that he will feel better if he does. Most of them are persuaded — and they do feel better."

Their performances also delighted the public. In the 1920s, WIP began to broadcast concerts from the "Boys Behind the Walls" featuring the ESP Band, as well as the prison's orchestra, string band and several soloists. The station received thousands of enthusiastic letters and telegrams after the first show, making the program a staple, especially around the holidays.

"Hundreds of thousands of Americans are tuning into these performances," McCool said. "There was mostly music, but elements of storytelling, joke telling to mix in the programming. This went on for decades after they started."

As that radio program might imply, the musical groups were an all-male affair. Though some women passed through Eastern State, the museum has no records of any playing in the bands or choirs, and by 1923, women were no longer held at the prison.

The men who participated brought all different levels of experience to band practice. Van den Beemt claimed to have just three men with any musical background when he took over the band in 1920, but he described at least one newcomer as a "born musician" with a future in the field. Their instruments were financed through the Honor and Friendship Club, an inmate welfare fund at the prison, and Edward T. Stotesbury, a wealthy Philadelphia banker. "He came to visit and he heard them performing," explained Erica Harman, manager of archives and records for Eastern State Penitentiary. "Apparently, he was a very avid amateur drummer, so he was like, these guys, they need drums."

The prison's musicians learned from world-class musicians apart from van den Beemt. John Philip Sousa, the composer of many marches and namesake for the sousaphone, also temporarily led the ESP Band after its members invited him to conduct. He shared with them arrangements of his newest pieces, but the band didn't just play other people's music. Eastern State Penitentiary has records of songwriting contests held in the prison, with cash prizes for the top two compositions. The winner took home $15, which would equate to about $280 today.

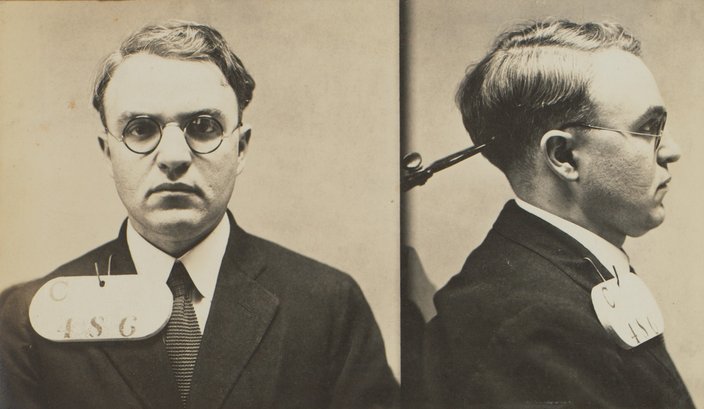

James Green, whose mugshot is pictured above, was the first prize winner of a 1922 composition contest and concert held on Labor Day at the Eastern State Penitentiary.

Staffers at the Eastern State Penitentiary, which houses its archives in the former dark room where inmate's mugshots were developed, see the spirit of the music program persisting in modern-day Pennsylvania prisons. The Lady Lifers choir at SCI Muncy, a medium/maximum security women's prison in Lycoming County, have performed in TEDx events posted to YouTube. McCool also highlights Songs in the Key of Free, a Philadelphia nonprofit that partners with incarcerated musicians to write and record songs.

"Music is important to musicians no matter where they are," McCool said. "But in a place like a prison, it can offer a little bit of a reprieve. It's also an opportunity for you to be around other people in a social setting, learn and develop a new skill. So it probably takes on a little bit more meaning for incarcerated musicians."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Provided image/Eastern State Penitentiary

Provided image/Eastern State Penitentiary