November 04, 2021

Courtesy/Sal Paolantonio

Courtesy/Sal Paolantonio

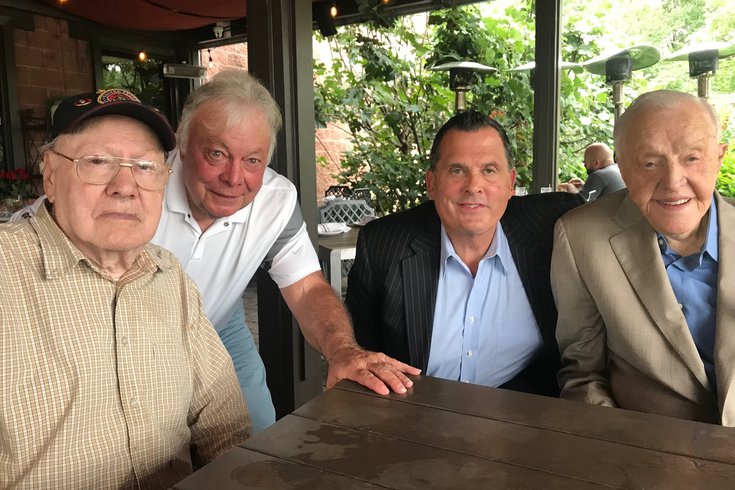

From left to right: Elmer Beach, Senator Jim Beach, Charlie Foulke III and Charlie Foulke Jr.

Those who have been through it never want to talk about it. It’s saved for only those singular ones like themselves, those have been to scorched-earth places no one wants to tread, who saw the cruelty of mankind at its utmost.

It’s like an unspoken code among service veterans who have survived combat. They keep it bottled up, a sort of survivor’s guilt that they’re burdened with for the rest of their lives as to why they’re alive and their buddies left behind are not.

On Sunday, immediately following the national anthem of the Eagles-Chargers game, 99-year-old World War II veteran Elmer Beach and 89-year-old Korean War veteran Charlie Foulke Jr. from South Jersey will be honored by the Eagles and Tri-State Toyota in their Salute to Service campaign.

"We think it’s pretty special and it’s unique how their stories came to us through a friend of the team who brought both Elmer and Charlie to our attention," said Eagles SVP of Media and Marketing Jen Kavanagh. "Elmer is 99 and served on Iwo Jima and Charlie served in Korea and was in Inchon. There are so few opportunities to celebrate these individuals, and it’s not just for us to celebrate them, but for the fans to celebrate them on Service day. We hope that they will see that this is pretty special. We do this throughout the year, and this is where we get the most fans to share that moment. It’s why we do this throughout the year and this is the least we can do to show our gratitude."

Beach and Foulke will probably be caught off guard by the roar of 67,000 people on their feet at Lincoln Financial Field, applauding the pair for the sacrifices they made many years ago.

Beach still bears the scar of a Japanese dagger on his leg from Iwo Jima 80 years ago and yells in his sleep, "They’re shooting at us, they’re shooting at us! Stay down, stay down!"

Foulke has a side story of screaming at a picture of the very men he served with, those who didn't make it, at a Korean War museum in South Korea, and being thanked by random South Koreans as he walked the streets of Seoul for their freedom.

Jim Beach, 75, the New Jersey state senator for the legislature's District 6, is the oldest of Elmer Beach’s seven children, ranging in ages from 75 to their late-50s. Elmer, a proud U.S. Marine to this day, survived Guam, Bougainville, Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima.

Charlie Foulke III, 59, is the lone surviving child of Charlie Jr., who was part of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s historic landing on Inchon in September 1950.

Both Charlie III and Jim get fragments of what their fathers endured in the wars. And their stories — even fragmented — are worth sharing.

* * *

* * *

Elmer is originally from South Philadelphia, and personally knew Bill Guarnere and Edward "Babe" Heffron, two of the soldiers whose stories were told in "Band of Brothers." Jim knew nothing about his father’s military service until he was in his 40s, when he obtained his father’s DD-214, a military form that explains a veteran’s military service record.

Jim always knew his father was a Marine, since he constantly had a Marine Corps t-shirt on or wore a Marine Corps hat. Jim never asked his father about his service — and Elmer offered little.

Jim often found out through others. He tells the story of a call from nowhere by an older gentleman named Nick Leakas in 2006. Leakas found Elmer through a Marine Corps alumni directory, hoping he got the right Francis "Elmer" Beach from South Philly. When Jim confirmed that he had, Leakas, in his 80s, wanted to drive from Michigan to the Red Cross building in Philly to see Elmer.

A day later, as Jim and Elmer walked up to meet Leakas in the parking lot, he told Elmer that he thinks of him daily.

"Nick says to my dad, 'I can’t believe it. Every morning when I wake up, I look in the mirror and I think of you,'" Jim recalled. "Nick told us about the time my father and him were in a fox hole together on Iwo, when a Japanese hand grenade fell between them.

"Nick told us how he froze, and how my father grabbed the hand grenade and threw it out. Then he reminded my dad how he saved his life. My dad said, 'Damn Nick, I don’t remember that.' That to me is my dad. If he knew about being honored at the Eagles, he’s going to be pissed. He hates the attention. He doesn’t think he did anything extraordinary."

"My father says he’ll never forget that kid’s face ... You find out why none of these guys really like talking about what they’ve been through."

Another time, a young, blue-eyed, blonde-haired replacement landed on Iwo. He clung to Elmer, asking him to bring him back home to his mother. He was scared to death. It’s one of the very few stories Elmer relates. That’s because it gnaws at him still. Elmer told the kid to stay with him, and he would make sure he would get home.

The pair had to move to another fox hole. Elmer gave the young Marine the option of going first, while Elmer covered him, or Elmer would move first and the Marine would cover Elmer. The young Marine went first.

Seconds later, Elmer found him impaled on a Japanese soldier’s bayonet, dangling in the air. The two killed each other. The young Marine had killed the Japanese soldier with a bayonet to the chest, the two connected in death by the tip of their guns.

"My father says he’ll never forget that kid’s face," Jim said. "My father said he always felt horrible that the kid never got home to see his mother. My father told me the vision of that kid always stays with him.

"It still bothers him that he couldn’t get that kid home. He didn’t know the kid’s name or anything about the kid. You find out why none of these guys really like talking about what they’ve been through."

To this day, Elmer maintains his weight, between 157 and 159 pounds, so he can still fit in his Marine Corps uniform — just in case the U.S. Marine Corps may need him again. His answers are short when asked what he recalls about Iwo ("the smell"), or Guadalcanal ("it rained every day").

One time Jim tried to organize a trip for Iwo Jima veterans to go back. Elmer refused. He lives Iwo every day. On the weekend of Sept. 12, Elmer turned 99. His family treated him to a getaway trip to the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. Elmer slept with one of his sons, and the next morning, Jim’s brother told him how Elmer started screaming at three in the morning.

Elmer was asleep, though he was back on Iwo, shouting "They’re shooting at us, they’re shooting at us, stay down, stay down."

"I’m extremely proud of my dad," Jim said, a crack of emotion in his voice. "He’s going to kill me for this with the Eagles on Sunday.

"But I have no problem saying it, my father is a true American hero."

* * *

* * *

When Charlie Foulke III was growing up, his father would lay in bed and pray every night for 15 minutes — and there was no way anyone would interrupt him. Charlie III thinks the reason was his service during the Korean War.

Charlie Jr. still has his DD-214 and won’t let his son see it.

In 2000, Charlie III and his father, a member of Tropical Lightning, the 25th Infantry Division, took a trip to Seoul, South Korea, to see the Korean War museum. On a tour bus together, Charlie Jr. turned to his son and whispered, "The last time I went through Seoul, the telephone poles were burning."

The two visited the 38th Parallel. They stopped by the Korean War museum.

"My father and I came across a blown up picture in there of some of the guys my father served with," Charlie III said. "The next thing you know, he was yelling at these guys, who were killed there, and he's screaming 'I told you not to go, and you went anyway.'

"I let my father be. I didn’t want to bother him. I asked him if he wanted to talk about it, and my dad said, 'Nah, I’m okay. I just had to get it out.'"

What happened next was incredibly heartwarming. Random South Koreans of various ages walked up to Charlie Jr. on the streets of Seoul and asked him if he was in the Korean War.

Charlie Foulke Jr. during his time serving in Korea.

Hesitant at first, Charlie Jr. acknowledged that he was.

"They came up to my father to say, 'Thank you for our freedom,' and that happened at least 10 times," Charlie III said. "They figured because of my father's age that he fought in the Korean War. At first, my dad was a little shocked. He wasn’t sure how they would react.

"I was very happy to see how they did react, because there were a lot of American soldiers who were killed over there in Korea, including some of my father's friends. The worst thing you ever want to hear in your entire life is 'Fix bayonets.' My dad told me about the time they were up and down a hill five times.

"They were so low on ammo, their captain said, 'Fix bayonets.' You fear it, because it’s time for hand-to-hand combat. It was about four or five in the morning when he heard what sounded like jets over them. It happened to be the battleship New Jersey, where he was from, firing rounds over his head. They wiped out everything.

"The Chinese army would come at you in waves. They would blow a bugle, and if there were 30,000 of us, they would send in 500,000. The first wave would have guns, the second wave would have swords and knives, and the third wave would pick up from the dead, he told me.

"He got the Purple Heart, but he never told me how. I got his DD-214, but my dad kept it."

"For these men to come back and never really complain, it’s why they’re the Greatest Generation and they deserve to be honored. These guys left their families and were shot at."

Charlie Jr. was born a poor kid in Camden, raised with 12 others in a row home by his maternal grandmother. He came back from Korea and on April 1, 1967, started what is now Cherry Hill Chrysler, Dodge, Jeep, and RAM.

The Foulke family now owns eight car dealerships.

As a teenager, Charlie Jr. interceded in a fight between a younger kid and an older man in Camden and put the older man through a glass window. A cop just happened to be a block away. Charlie Jr. got arrested and was facing either 90 days in jail or enlisting in the military.

He opted for the army. Three months later, Charlie Jr. got called up and soon was shipped to Korea.

"I'm happy to see my father happy, and I'm sure Sen. Beach feels the same way," Charlie III said. "I get emotional thinking about it. Those guys don’t want any attention. What they went through is amazing. Some days you wonder what it would be like to go through what they did.

"When people talk about sacrifice, those guys sacrificed. They were drafted and put in the army and it’s amazing to me how much they sacrificed. Those guys wanted nothing for it. It's why they’re called 'The Greatest Generation.'"

The Greatest Generation is a rapidly dwindling group, with special men like Elmer Beach and Charlie Foulke Jr. becoming fewer. They came home, but they were never really whole again. A part of them will always be where they left their buddies, like Charlie Jr. yelling at the photo of his comrades in Seoul, and Elmer haunted by the face of the young marine.

"I think it’s why my father says his prayers every night," Charlie said. "For these men to come back and never really complain, it's why they’re the Greatest Generation and they deserve to be honored. These guys left their families and were shot at.

"My father loves this country. He always says to me, where can a poor kid from Camden end up starting from nothing and get to where he is? My father is a humble, kind guy. I think my father says his prayers and maybe it’s asking for forgiveness, because I don’t know what he did in Korea, and I'm sure it wasn't good.

"I haven't told my dad about Sunday yet."

Joseph Santoliquito is an award-winning sportswriter based in the Philadelphia area who has been writing for PhillyVoice since its inception in 2015 and is the president of the Boxing Writers Association of America. He can be followed on Twitter here: @JSantoliquito.

Courtesy/Foulke Family

Courtesy/Foulke Family