August 20, 2021

Courtesy/David Barnes

Courtesy/David Barnes

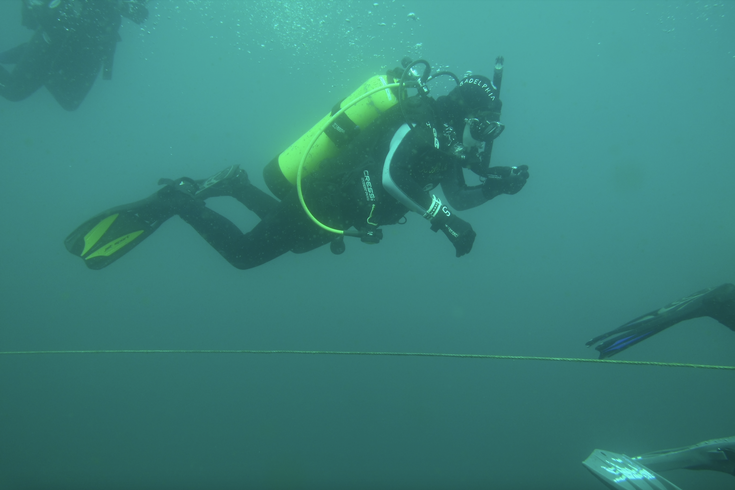

Scuba divers swim at Dutch Springs, the 50-acre quarry lake in the Lehigh Valley on a property split between Bethlehem and Lower Nazareth. The owner of the 40-year-old lake and aqua park has sold the land to a developer with plans to build a large warehouse on the site. The future of the lake, a staple of the diving community in the Northeast U.S., is in jeopardy.

For the past four decades, a 50-acre lake in the Lehigh Valley has been the pillar and lifeblood of the region's scuba diving community.

It may soon be a fenced-off casualty of Pennsylvania's warehouse boom – a proliferation of industrial parks that have increasingly shaped the state's economic and physical landscape.

Located two hours north of Philadelphia, along the border of Lower Nazareth and Bethlehem townships, in Northampton County, Dutch Springs emerged from the remains of the National Portland Cement Quarry at Brodhead. The former limestone mine and cement plant flourished for decades until the operation folded in the mid-1970s, prompting the creation of a unique diving campground, aqua park and adventure course on a portion of the property.

"It's our Quarribbean, if you will," said Dave Barnes, owner of Scubadelphia, a dive center and gear shop in the Frankford neighborhood, whose scuba certification instructors are among the busiest in the Delaware Valley.

Spring-fed by an underground aquifer, the flooded quarry has served as an idyllic lake and training ground for generations of professional and recreational divers. With depths reaching 100 feet in some parts, Dutch Springs is the Northeast's primary locale for dive centers to conduct certifications and hold other outings that keep the scuba community connected and growing.

Along the floor of the quarry are a number of sunken vehicles and structures to explore, including a Philadelphia trolley once used at the nation's Bicentennial Celebration.

"They've sunken school buses there, airplanes, jets," Barnes said. "There's a lot of different attractions that new divers love. It's very exciting for somebody who's never seen that before. And then you take them to an airplane assessment or a jet, or the trolley. It's a park for divers – and that's very cool."

It came as a shock this month – sudden, but not unpredictable – when news reports surfaced about a developer's plan to construct a pair of warehouses on consolidated lots that would include the Dutch Springs property and its prized lake. The proposal is from Dallas, Texas-based commercial real estate developer Trammell Crow, which has completed other projects in the Lehigh Valley.

Within five days, a petition to save Dutch Springs collected more than 5,100 signatures in a bid to draw attention to the warehouse proposal and the threat facing the lake if the divers don't gain a voice in the planning process.

"Divers, dive shops and friends of the community were blindsided this past Friday when it was announced that Dutch Springs will be sold to a warehouse developer, and could be closing its doors as early as January 2022," wrote petition organizer Janine Rajauski, a Philadelphia-based scuba diving instructor. "This has left the dive community scrambling, heartbroken and eager to make a difference and stop this development to maintain their education center."

The clock is already ticking on the diving community, but then again, that's the kind of pressure that might be embraced by people who spend prolonged periods of time underwater.

The future of Dutch Springs would not be in question if it weren't for the sale of the property by husband-and-wife co-owners Stuart and Jane Wells Schooley. The couple was part of the original group that stepped in and reinvented the abandoned quarry before opening it as a scuba diving facility in 1980.

Approaching retirement after years of dedication to Dutch Springs, the Schooleys are sitting on a prime piece of real estate, about 95 acres in total, that they have chosen to sell.

"We didn't expect this to happen with Dutch Springs," said Barnes, whose business uses the lake at least once a month with groups of 30-50 diving students. "We always knew it could, but (not) this quickly – there was never a meeting with us. (Stuart Schooley) never came to us and said, 'I'm planning on doing this, do you guys want to offer me money?'"

Even had Schooley made this gesture to divers, Barnes knows it likely wouldn't have mattered.

"It would have been a great feeling, but realistically, I don't think we could come up with the millions of dollars he probably was offered for that property," Barnes said. "But if he had said, 'What can I do for you?' we might have asked to buy the lake part or have it leased to us, and the rest of the property go to the developer. He deserves to sell it and do whatever he wants to do with it, but it does affect my dive center as well as dive centers for hundreds of miles around here. I don't think some of them are going to survive, especially through COVID and just barely hanging on."

Schooley did not return a phone message left with the Dutch Springs office, asking to discuss the sale of the property and what it could mean for future access to the lake.

Dutch Springs is a two-hour drive north of Philly, in Northampton County. The lake emerged from the remains of cement quarry. The former limestone mine and cement plant operated for decades until the mid-1970s.

Earlier this month, Lehigh Valley Live reported that the developer wants to consolidate the Dutch Springs lot at 4733 Hanoverville Road. with portions of a neighboring lot to the west. The property would then be subdivided into two lots.

In Lower Nazareth, plans call for a 295,750-square-foot industrial building, while in Bethlehem, the developer seeks to construct another 299,796-square-foot industrial building and a 173-square-foot guardhouse.

Trammell Crow, a well-established developer across a range of commercial sectors, did not respond to a request for more information about its proposal.

The company previously developed the original Lehigh Valley Trade Center in Bethlehem in 1985 and already has gotten approval for the Lehigh Valley Trade Center II, another 527,500-square-foot warehouse project planned nearby Dutch Springs on Hanoverville Road, also straddling Bethlehem and Lower Nazareth.

What's not yet clear about the developer's plans for the Dutch Springs property, specifically, is what will happen to the lake that's so important to the diving community.

Though there has been some indication that access to the lake might be maintained for emergency services to conduct public safety training, that's ultimately only one slice of the diving population that currently uses the lake.

"Public safety would be rescue and response," said Pat McLaughlin, a dive safety officer at Camden's Adventure Aquarium and an active dive instructor. "I don't want to speak negatively about that, but the interesting thing about those programs is that a lot of places have dive teams and do a lot of training, but for what they actually do, they don't get called on that much. It's more something you join to train and hope you never have to actually go do it. My feeling is that them saying they're allowing access to public safety is probably just a PR move."

McLaughlin, 32, grew up in the Philadelphia area and spent most of his weekends as a kid at Dutch Springs. His father was a dive shop owner and scuba instructor who regularly took McLaughlin and his twin brother to the lake.

"We spent pretty much every weekend up there through my childhood," McLaughlin said. "It's kind of like our version of a shore house. We had a camper up there that we'd stay in. My dad would teach all weekend. I got officially certified to dive on my 12th birthday up there."

McLaughlin says the impact of Dutch Springs over 40-plus years has been far-ranging among divers, who recognize it as a well-run place of learning and good times.

"If you're a diver, chances are you've heard of Dutch Springs. Anywhere I've gone diving – Pacific Northwest, down in the Caribbean, Florida – people ask where you're from and if you say Philadelphia, they say, 'Oh, you must have dove that quarry up there,"' McLaughlin said. "It's like the mecca of the local dive community. You get some people who go up there in the spring to get the cobwebs off and test equipment. You get people that go there just because it's so enjoyable for diving. I probably have about 1,500 dives in there, and I don't get bored."

This jet, submerged at Dutch Springs, is among multiple, large vehicles that have been sunken at the popular Lehigh Valley lake. Divers train by exploring the vehicles.

"He's put more than just a career into creating what it is. And for what he's done for the dive community, I don't think we're all necessarily as appreciative as we should be, so it's been kind of a thankless experience for him," McLaughlin said. "I think that's why this sale was kind of done under the radar and everyone kind of found out through news articles."

Considering the lucrative sum for the land that Schooley could get from a major development deal, McLaughlin understands why it may have been easy for him to disconnect from the concerns of divers.

"He's earned his retirement. He would never get from the dive industry what he gets from this kind of deal," McLaughlin said. "If I were in his position, I think everyone out there agrees, it's a no-brainer to do what he did. It just kind of sucks for us."

The Lehigh Valley has been ground zero for the bumper crop of warehouses that have sprung up across Pennsylvania during the last decade, a phenomenon examined earlier this year by the New York Times.

With its strategic proximity to New York City and other commercial hubs, the Lehigh Valley is a magnet for projects like the one proposed at Dutch Springs, a property that historically had been Moravian farm land prior to becoming a quarry.

Billions of dollars have been invested in repurposing existing manufacturing facilities and building new warehouses on coveted land that grows scarcer by the year.

In some cases, warehouses are built speculatively, well before a tenant has even signed on to a project. They're billed as a valuable logistics hub and sources of jobs in a region that has seen its manufacturing legacy diminish over the recent decades.

Warehouse jobs don't typically pay as well as the heavy industry positions of yesteryear, but their prevalence in the Lehigh Valley marks a transition that's undeniably underway.

Northampton County Executive Lamont McClure Jr. is opposed to the warehouse project proposed at Dutch Springs. The county has limited input and no authority over the planning process, but McClure wants the region to better understand what's at stake when considering such proposals.

I hate the term 'development' for that ... how can you be developing something when you're fencing off and taking away something that's already so perfect for a very specific use?" – Pat McLaughlin, diving instructor

"I'm not in favor of any more warehouses in Northampton County," McClure said. "You have to balance economic development and job creation with land preservation. We have reached a tipping point in Northampton County where that balance is tipping toward job creation and economic development, but of the sort that is warehouse-driven. One of the concerns we have with job creation that's driven by warehouse development is that – you know, in 10 years, the logistics businesses, they're not planning on using human beings in these places anymore."

Much has been made of automation wiping out warehouse jobs for people – how quickly and thoroughly is still a matter of debate – but there's reason to believe the jobs that exist alongside more machines may be of lesser quality and stability. And if that's the case, McClure believes the decisions facing planners in the Lehigh Valley are becoming more existential, not just in terms the work residents do but how it changes communities.

"We're very concerned that we're losing vital farm land and environmentally sensitive land to these large, hundreds of thousands of square-foot development projects that aren't going to employ any people in 10 years," McClure said. "Our quality of life is at risk. That's what we're really working on here: the balance between the very high quality of life we enjoy in the Lehigh Valley versus the notion of becoming some kind of inland port."

McClure hasn't spoken directly with the developers of the Dutch Springs project, but he believes their aim is to wall or fence off the quarry.

"I think the developer probably wants to relieve itself of the potential liability of the quarry," McClure said. "I'm not sure it knows how best to do that. In Northampton County, we're trying to figure out how the quarry might possibly fit into our overall parks and environmentally sensitive preservation program. We are thinking about it, but those programs are preliminary."

In the past few years, Northampton County has invested about $12 million into farmland preservation and open space. And while McClure may attempt to seek some compromise in the Dutch Springs proposal, he conceded that he's not overly optimistic about the outcome.

"I know it's important to the diving community and to first responders to have the quarry for diving and diving training," McClure said. "From the county's perspective, we really don't want to see anymore warehouses – and we really don't want to see any more farm land, open space or other sensitive land be plowed under and paved over for warehouses."

The breakneck pace of development around Dutch Springs has been obvious, even to the divers.

"The past 10 years I've owned Scubadelphia, and even before, it used to be quiet at night," Barnes said. "Now you have trucks beeping and backing up, speeding down the road. It's gotten louder. I don't know how the neighbors deal with that, either. There's a lot of homes in that area."

McLaughlin said the location around Dutch Springs – wedged between Pennsylvania Routes 512 and 191 and U.S. Route 22 – has transformed dramatically during his lifetime. The whole south wall of the property used to be trees, but there are now warehouses right up to the edge of the quarry cliff.

"You could do a night dive at Dutch Springs and not even take a flashlight because there's so much light pollution in the area," said McLaughlin, whose senior project in college was a 70-page case study on the landscape history of Dutch Springs. "Even camping out and sleeping up there, all night you hear the traffic from Route 22, or you hear sounds from the industrial parks and the airport. We used to drive up and it was all farm fields when you get off Route 22. Now it's all industrial parks. You can't even take the same road in because they diverted the road and tore down an old diner that was there. You have to literally detour through an industrial park."

The available land in the area is so limited and sought after, at this point, that McLaughlin feels the Dutch Springs lake is just an afterthought to developers.

"As far as a moneymaker, diving is not worth that land – that's why Stu had to make the Aqua Park," McLaughlin said, referring to Dutch Springs' expansion in the 1990s to include other recreational facilities. "It's more so an iconic place, and I think that's why the petition is gaining steam. You ask anyone in the area where they got certified to dive and they'll tell you Dutch Springs."

Rajauski, the creator of the petition, agrees with McLaughlin that Schooley and his wife deserve to enjoy their retirement years, as well as credit for what they've done for the dive community. She hopes Schooley will hear the calls for the lake's preservation and advocate for it to remain a student certification center that continues to grow the Northeast's diving community.

"It’s heartbreaking to think of how this will impact the community we have all worked so hard to grow," Rajauski said. "Dutch really is a safe place for students to learn, and like I said in the petition, a place for all the instructors to see each other and catch up. It’s a family reunion each month. It's unimaginable to think all of that could be thrown away for more warehouses."

A view of Dutch Springs, with smokes stacks from the site's shuttered cement plant in the distance.

"Everybody's hush-hush about this, so I don't know what the exact plan is," Barnes said. "I don't know if they're going to backfill that water in."

At Bainbridge Quarry, once a 27-acre spring-fed lake in Lancaster County, Barnes saw a great diving resource disappear that way after the land was sold to the county's solid waste management authority in 2015. The lake was used to cool turbines and was eventually emptied. It's illegal to enter the property.

The Dutch Springs proposal seems to be following a well-oiled playbook for development in areas that are subject to community pushback. Resistance is made more difficult, in this case, because many of the divers and businesses who use Dutch Springs don't live right in the area.

"From what I've heard of the plans, they're just going to fence off the lake and build around it, which is horrible," McLaughlin said. "I hate the term 'development' for that, because how can you be developing something when you're fencing off and taking away something that's already so perfect for a very specific use?"

At this late planning stage, the game plan for the dive community is to apply pressure by illustrating the void that would be left if it's no longer accessible.

"Everyone's trying to kind of approach it from different angles, just creating some noise around it and making people aware of what we stand to lose," McLaughlin said.

Throughout August, discussion about Dutch Springs' future has been a hot topic in the diving community, both online and among colleagues in the industry.

In addition to the support, McLaughlin also has seen some cynicism about the petition, mostly coming from hardened, veteran divers who consider the ocean the ultimate place to dive, not a 50-acre training lake.

"People on the internet say, 'What's a petition going to do?' All over Facebook and other groups, people just say money talks. If you want to save it, why don't you make an offer?" McLaughlin said. "Diving can be an ego-driven sport, and there's some macho-ness, so people are like, well, if Dutch Springs is closed, then come dive the ocean ... You get a lot of people saying, 'It's just Dutch, no one's going to miss it' – but I think we really will if we can't keep going there. It's going to affect us a lot more than people want to think."

The website for Dutch Springs has a bright red banner on its homepage noting that Friday, Aug. 20, is the last day the Aqua Park and Aerial Park will be open.

Scuba diving in the lake will continue through Nov. 14, and again for a special event on New Year's Day.

Barnes suspects that Jan. 1 will be the final day for general diving access at Dutch Springs, unless some other arrangement is made to secure its future.

"We're trying tirelessly to find some other places that can mimic Dutch Springs, but there's nothing comparable to that," Barnes said. "They cornered the market around here for many years. We're not totally sure what to do, and we're hoping somebody can save the lake part of it – at least for us."

Pennsylvania and New Jersey have plenty of other quarries, but none are anywhere near as safe as Dutch Springs, and there's red tape to navigate even to gain access to them. The Delaware Water Gap has some decent areas to dive, McLaughlin said, and New Jersey has a few gems and there's always the shore – but it's not the same.

"One of the things that really sets Dutch Springs apart – why it's so important to us – is that it's set up perfectly for diving. If is by far the safest training facility, probably in the country. At all times, there are three lookout stations for dive patrol, which is like lifeguards for divers. And there's usually a paramedic on site. I think the biggest loss is the ability to train new students. There's nowhere else in the Northeast that you can guarantee such good conditions and take students up in the volume that you have at Dutch Springs."

The sun sets over Dutch Springs in Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley.

"We love diving the shipwrecks in New Jersey," Barnes said. "We were just out there this past weekend and Saturday was beautiful. We had a great time diving there. Then Sunday, the boat left the inlet and the waves were so crazy, we had to turn around and come back in. That doesn't happen at Dutch Springs. We can go there any time. If it's raining or windy, it's fine. We can get in and out of that water easily. People don't get seasick. We can easily certify students."

At Dutch Springs, Barnes would barbecue all weekend and turn training into a big social event for students, staff and friends. There simply isn't another place like that in the region to accommodate divers.

With time running down, Barnes said he's contacted local police departments, asking about quarries officers have to monitor because of problems with teenagers drinking and jumping into the water, sometimes getting hurt and requiring assistance.

"If we can get a hold of one of the owners of those quarries, and purchase or lease it, then we would patrol it ourselves," Barnes said. "That would help us and help out the land owner. We'll make things work. We'll be OK."

But Barnes admitted he's spoken to colleagues at other dive shops, and he isn't so sure they will make it if Dutch Springs is closed.

"I don't know if some the smaller shops are going to survive," Barnes said.

During the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, Dutch Springs was closed to divers until July 2020. McLaughlin, who trains divers for a shop in Horsham, said he noticed then that the local dive community was at a loss for what to do. When he'd mention other places to go, some of them weren't interested.

"They were just like, nah, we'd rather not teach right now," McLaughlin said. "So a lot of the shops and instructors are probably not going to bother if Dutch isn't there. We could lose a lot of momentum that we've gained as far as new students and new divers. A couple of years down the line, you're going to see a decrease in the quality of divers that are out there because they have no place to go and practice. It's kind of a scary thing."

Rajauski was certified by Scubadelphia at Dutch Springs with her siblings, including a brother with a disability, and fell in love with the environment. She went on to establish a program, The Miss Scubadelphia Advanced Training Grant, that funds opportunities for women interested in diving.

"The dive community welcomed me with open arms and really empowered me to continue diving," Rajuaski said. "It was really important for me to pass that on to other women. If I didn’t get open water certified at Dutch and have such an amazing experience with the community as I have, I don’t think I’d be an instructor or have started the grant."

The divers haven't given up hope for Dutch Springs just yet.

"At this point, we just want access to the lake, and hopefully whoever is there works with us," Barnes said. "We'd be willing to work with anybody to buy the lake or lease it."

McLaughlin acknowledged that the road ahead to preserve Dutch Springs isn't easy. It will require coordination among divers and preparation to address the liability issues that could arise from shared control over the lake.

"In a perfect world, since the sale is through and it sounds like there's no stopping that, what I'd like to see is Stu, his wife, the developer and the counties and local governments work together and figure out a way to keep access to the lake open for the diving community to use," McLaughlin said.

Courtesy/Pat McLaughlin

Courtesy/Pat McLaughlin Courtesy/David Barnes

Courtesy/David Barnes Courtesy/Pat McLaughlin

Courtesy/Pat McLaughlin Courtesy/Pat McLaughlin

Courtesy/Pat McLaughlin