July 27, 2016

Source/Nutrigenomix

Source/Nutrigenomix

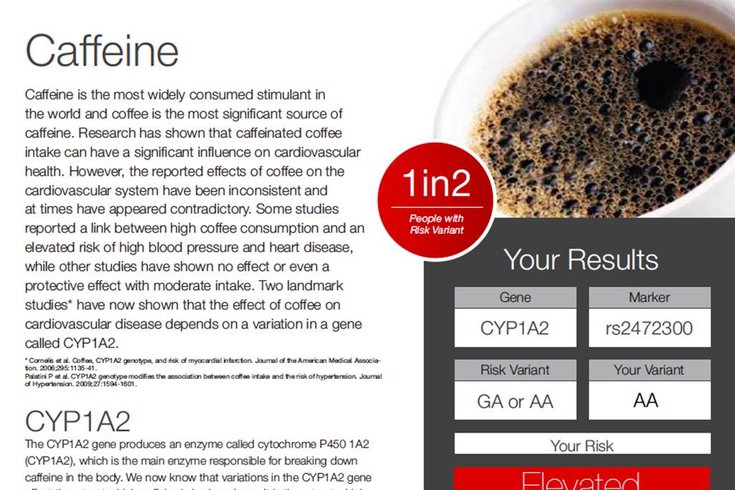

Nutrigenomix and other companies offer detailed reports containing personalized dietary recommendations based on genetic profile. This sample Nutrigenomix report shows personalized information on coffee metabolism. "Coffee consumption recommendations are generally 4 to 5 cups per day, but that amount is fine for only half the population," says company founder Ahmed El-Sohemy. "If you're a slow metabolizer, any more than 2 cups a day will increase your risk for a heart attack.”

Over the last several decades, coffee — much like dark chocolate, red wine, and certain types of fat — has seen its reputation swing from one extreme to the other. Once thought to stunt growth in children and cause heart problems, the caffeinated beverage has been given the official green light in the latest version of U.S. dietary guidelines, which state that three to five cups per day can be part of a healthful diet.

But despite being the most widely consumed stimulant in the world, caffeine doesn't affect everybody in the same way. In fact, a gene called CYP1A2 distinguishes between “rapid” versus “slow” caffeine metabolizers — and the latter group has an elevated risk of heart attack with greater coffee intake.

This finding is among many supporting the idea that humans physiologically respond to foods differently depending on their genome — and with a simple saliva swab, a growing number of companies will sell you a personalized “DNA diet” of your own. Startups like DNAFit and Nutrigenomix provide customers with detailed reports containing personalized dietary recommendations based on their genetic profile.

While the science behind some of these recommendations may have valid roots, some argue that such advice jumps the gun. Research in nutritional genomics remains in early stages, and the links between diet, genotype and disease risk often go beyond a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship.

“The potential value of personalized diets lies in the fact that many of the 'rules' of nutrition (e.g. avoid high cholesterol foods) are not true for everyone,” said Patricia Danzon, a professor of health care management at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. “But although [personalized diets] may happen eventually, we are far from that at present.”

Danzon's main area of research lies within the pharmaceutical industry, and she previously investigated the use of genomic differences to personalize drug treatment. The rising popularity of DNA diets goes hand in hand with the excitement around such personalized medicine, which tailors health care to each patient's genetic makeup rather than using broad “one-size-fits-all” treatments and recommendations.

Perhaps the most recognized example involves screening for mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which greatly increase a woman's lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Physicians recommend those who test positive get screened earlier and more frequently.

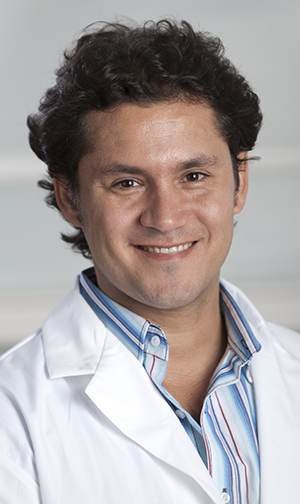

“In the pharmaceutical world, the same drug will be good for some people and bad for someone else,” said Ahmed El-Sohemy, an associate professor of nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto who founded Nutrigenomix. “Similarly, the concept behind [nutritional genomics] is that one man's food is another man's poison.”

Ahmed El-Sohemy, an associate professor of nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto, founded Nutrigenomix. '...The concept behind [nutritional genomics] is that one man's food is another man's poison,' he says

“Our field has been plagued with inconsistent findings, and a big part of that is because people respond differently to foods,” he said. “Coffee consumption recommendations are generally 4 to 5 cups per day, but that amount is fine for only half the population. If you're a slow metabolizer, any more than 2 cups a day will increase your risk for a heart attack.”

Nutrigenomix uses a panel of 45 genetic markers that give personalized information on caffeine metabolism; the absorption and breakdown of nutrients like vitamin C, folate, and calcium; food intolerances such as gluten and lactose; and safe amounts of saturated and omega-3 fats to consume. El-Sohemy stresses that his tests are only available though a healthcare professional and not sold direct-to-consumer, unlike some of their competitors. Currently, almost 3,000 clinics in 22 countries offer the company's tailored dietary reports.

But other experts warn that more research needs to be performed with large cohorts adhering to specific diets in order to give such detailed and accurate advice based on those markers. In 2014, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics stated that while nutritional genomics is an emerging science that holds promise for tailoring diet to a person's genotype, giving personalized dietary advice based on genetic testing is not ready for routine practice.

“The basic problem is that most diseases are not monogenetic, that is, they can be influenced by multiple genetic differences and also by other environmental factors, including nutrition,” said Danzon. “Similarly, the effect of a particular diet or food may depend on multiple genes and on other environmental factors.”

“The companies I am familiar with all base their predictions on established scientific studies that have shown direct effects of certain genetic variants,” said Rasmus Nielsen, a professor of integrative biology and geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley. “However, there are very few intervention studies that show what actually happens if people switch their diet, for example, in response to genetic information they have obtained.”

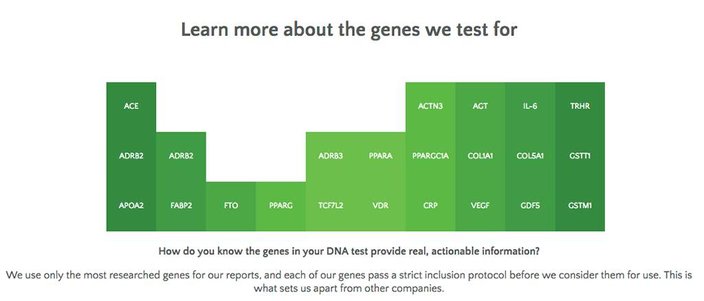

A chart on the DNAFit website shows prospective customers which genes are tested.

Very few studies cited by nutritional genomics companies are truly designed to provide dietary guidelines, and are often performed in a specific population group — usually people of European descent. But El-Sohemy responds to these criticisms by noting that the vast majority of today's widely accepted dietary guidelines are not based on randomized clinical trials.

"It's easy for a naysayer to say 'we need more evidence' because that's the 'safe' and conservative thing to say," he said. "Those who claim 'we need results from a [randomized clinical trial]' would be hard pressed to show you that level of evidence for most of the dietary advice they offer."

The science behind nutritional genomics does appear to have merit, however. Last year, Nielsen and his colleagues published a study revealed that mutations in the DNA of Inuits and their Siberian ancestors play special roles in fat metabolism that help them counteract the negative effects of eating lots of animal fat. The findings deciphered a decades-old medical mystery — how Inuits living in remote Greenland managed to avoid cardiovascular disease despite subsisting on a high-fat diet of fish and marine mammals.

Previously, scientists had concluded that the Inuit diet — chock-full of omega-3 fatty acids, a type of fat used in cell membranes throughout the body and found in fish oil — held the key to their robust, disease-free hearts. Word spread, and soon fish oil pills started flying off the shelves of health food stores around the world.

“As a species, we have adapted to many different environments and diets — some areas are entirely vegetarian, some are entirely meat- and fat-based,” said Nielsen. “It suggests that we're different based on what is healthy for us to eat, and we can use genetic information to guide our choice of diet.”

Source/www.dnafit.com

Source/www.dnafit.com