May 26, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Henry Pennock served in the 101st Airborne Division during World War II, participating in the Battle of the Bulge.

The first time Henry Pennock flew on an airplane, he jumped out.

That was the level of courage necessary to serve as a paratrooper in the U.S. Army during World War II.

Many of the American soldiers sent to Fort Benning, Georgia couldn't complete the training required to literally jump into battle. Pennock was one of the few that did.

"Close to 8,000 guys were flying in my class," Pennock said. "Only about 2,000 or 2,500 got their boots. Most of this wasn't that they weren't physically capable. It was mental."

Now 92, Pennock, of Levittown, Bucks County, earned three Purple Heart decorations and three Bronze Star Medals for his service, which included combat in the Battle of the Bulge and a trip to Adolf Hitler's Eagle's Nest.

Pennock is more than 70 years removed from the battlefield, but his memory of his wartime experiences remains sharp.

He can recall the frigid winter in Bastogne, Belgium and the horrors of liberating a concentration camp. And remember the thrills of parachuting from the sky and the friendliness of the German civilians in Berchtesgaden.

Pennock is quick to share stories of camaraderie – like the way he and other wounded soldiers snuck out their hospital beds to go dancing at night. But he doesn't shy from the harsh realities of war, including the loss of life.

Pennock remembers lying by a stone fence with another soldier as they went to get ammunition. Suddenly, his comrade was struck down by a sniper.

"They were the kind of things that happened when you're in combat," Pennock said. "You had to accept it. A lot of things – you got to a point where you just felt there was no way to really protect yourself. You just had to do what you had to do."

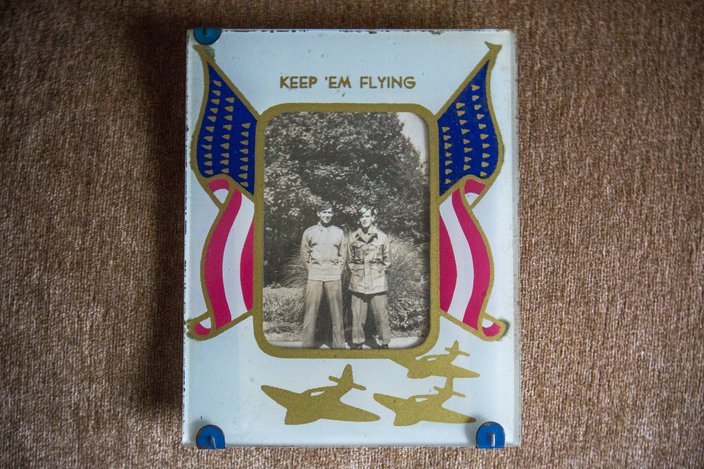

This photo of Henry Pennock, right, and his friend Mickey Deffley was taken during WWII.

Pennock wanted to join the U.S. Army Air Forces – a precursor the Air Force – upon graduating Altoona High School in 1943. But a failed eye test forced him to consider an alternative path to the sky.

He signed up to become a paratrooper – mostly because he noticed that women seemed impressed by military parachutists. It didn't hurt that jumpers were paid an extra $50 each month.

This time, Pennock memorized the eye chart. He got in.

"Bastogne, it was unbelievable. It was mayhem, with trees coming down. Everything under the sun was hitting you. It was a miracle that you could survive under so much firepower." – Henry Pennock of Bucks County, WWII paratrooper

"Once I was in a while I told the sergeant, 'My eyes are bothering me,'" Pennock recalled. "So, I go down to the doctor. The next thing I know, I had glasses. ... My eyes weren't that bad. Not for that job, you might say."

Pennock spent four weeks at Fort Benning completing his paratrooper training. Initially, he leaped from the tops of telephone poles onto big piles of sawdust. Then came a jump from a 350-foot tower with a tiny parachute.

"That scared the shit out of us," Pennock said. "It's like standing on top of a building, if you can imagine. And more guys quit that than anything."

By the time Pennock completed his training, which was followed by a week of combat drills, he had jumped from an airplane five times, including once at night.

Ready or not, he was headed to Europe as part of the 101st Airborne Division.

"It was a thrilling time in your life, whenever you did these kinds of things that you wouldn't do normally," Pennock said. "But under the military, it was entirely different."

Pennock arrived in Bastogne in time for one of the preeminent moments of the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive campaign on the western front in the European Theatre during World War II.

He was not there two days before the Germans began bombing the Belgian city in December 1944, surrounding the 101st Airborne as its troops scattered to the city's outskirts.

"Bastogne was so important because the Germans wanted to get to Antwerp," Pennock said. "They had to go through Bastogne to cut off the Allied advance. Patton, with his tanks, was up in the Holland area yet."

The surrounded Allied forces famously fought the Germans for days in brutal conditions. The frigid winter had prevented them from receiving tactical air support and supplies, leaving them with dwindling rations, ammunition and medical supplies.

Near Christmas, Pennock said, the troops received hot turkey and mashed potatoes dropped from planes passing overhead. Pennock wisely kept one of the parachutes from an airdrop as a makeshift blanket.

Elements of Gen. George Patton's Third Army finally broke the siege and liberated the 101st Airborne on Dec. 27, 1944.

Troops with the 101st Airborne Division retrieve supplies from airdrops during the siege of Bastogne in December 1944.

All told, Pennock spent about 30 days fighting in Bastogne.

"Bastogne, it was unbelievable," Pennock said, referring to the Germans bombing the city down to the basements. "It was mayhem, with trees coming down. Everything under the sun was hitting you. It was a miracle that you could survive under so much firepower."

Pennock did not leave unscathed.

He suffered shrapnel wounds to his shoulder and arm. And his feet were nearly frost-bitten. He received a Purple Heart for each of his injuries.

"All of the tanks we had in Bastogne were 75mm," Pennock remembered. "They'd bounce right off the Tiger tanks. They couldn't really penetrate. The bazookas we had, we'd use (them) – but there were only so many of them.

"When Patton finally liberated us, he had 125mm cannons. They could hit the Tiger tanks and get into them. That's how we were actually liberated."

From Dec. 19, 1944 to Jan. 6, 1945, the 101st suffered huge numbers of casualties: 341 killed, 1,691 wounded and 516 missing, according to the United States Army Center of Military History.

Pennock was taken to St. James hospital in Belgium to treat his shrapnel injuries before heading to a hospital in Chester, England to allow his frozen feet to recover.

There, he and others would sneak out at night to go dancing.

"We'd hide our stuff underneath the mattresses," Pennock recalled. "We realized that circulation was really what you needed."

The siege of Bastogne proved to be the worst fighting Pennock said he witnessed. But the horrors weren't over.

After recovering from his injuries, Pennock rejoined the 101 Airborne in time to help liberate the Kaufering concentration camp near Landsberg, Germany in April 1945.

"It's hard to imagine what you saw there," Pennock said. "You've seen pictures of it. We weren't allowed to give them anything. If you gave them a chocolate bar, it would kill them."

The Kaufering concentration camps housed thousands of prisoners, mostly Jews, in poorly heated, earthen huts. They were forced into hard labor and suffered from malnutrition and disease.

"They were so bad off – they needed medical attention," Pennock said. "Even though you wanted to help them, you just felt so bad when you saw how they were mistreated."

The war, however, was winding down. The 101st Airborne headed toward Berchtesgaden in southern Germany. There, Nazi leaders had a nearby outpost in the Bavarian Alps, including a mountaintop hideaway known as the Eagle's Nest.

"When we got in there, surprisingly, there was hardly any resistance at all," Pennock said. "All the people we were looking for were gone. Most of the people were wealthy Germans who spoke perfect English. Half of them were agreeable to Hitler and half of them probably weren't – but they had no choice."

Pennock said he only took one trip up to Hitler's Eagle's Nest – and he had to use the stairs since the elevator shaft had been blown up. Otherwise, he remained in Berchtesgaden as the Germans neared an unconditional surrender.

But the Germans' formal surrender on May 8, 1945 did not mean Pennock would get to go home. Rather, he prepared to head to the Pacific Theater, where the war was ongoing.

Pennock was sent to Paris, where he performed his final jump – a demonstration for a bond drive.

On Sept. 2, 1945, the Japanese surrendered.

"Everybody was partying and having a good time," Pennock said. "Naturally, we all felt great. We knew we weren't going to go any further. We were going to come home."

That came aboard a Victory warship, a stark contrast from the French luxury liner that first rushed him across the Atlantic Ocean. The trip home took 23 days.

And he spent it seasick.

"Coming back, it was unbelievable," Pennock said. "Everybody, even the crew, was so sick. One day, we did a mile where the waves were 40 or 50 feet high. I know I didn't eat anything for seven or eight days."

Still, he was coming home.

Today, Pennock still feels the effects of the war. His left ankle, injured during one of his seven jumps, lacks cartilage, inhibiting his ability to walk. It also bears scars of the frozen feet he sustained at Bastogne.

But he remains proud of his service.

An American flag flaps in the wind outside his Bucks County home, where he has lived since 1956.

Inside, Pennock's medallions hang in the living room. He's held onto his Eisenhower jacket and a few Nazi arm bands he found during the war. And he keeps the bowie knife that he carried throughout the war tucked away.

"My attitude now is – keep a strong military and it will keep us safer than anything else," Pennock said, who has five children and more than 20 grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Henry Pennock has saved a Nazi arm band that he picked up while serving in Europe as well as the Eisenhower jacket he wore during the war.

Military service runs deep in his family. Both the fathers of he and his second wife, Elaine, served in World War I. They had many relatives serve in World War II. And their son, Henry, was in the Navy during the Reagan administration.

"We have to have a strong military," Pennock said. "I know it's costly and a lot of people don't believe in it – but I do because I could see how overwhelmed we were in World War II. If it wasn't for us, I don't know what would have happened in the world."

After the war, Pennock briefly worked for the Altoona News before taking a job with the Seaboard Finance Company. He spent the remainder of his career working in finance before retiring in 1985.

That career placed him on his first civilian flight – a business trip to California. Upon landing, one of the executives asked him whether he enjoyed the flight.

"I said, 'It was great,'" Pennock recalled. "'First time I ever landed in a plane.'"

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice U.S. Army/via Wikimedia

U.S. Army/via Wikimedia Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice