April 17, 2020

VSRao/Pixabay

VSRao/Pixabay

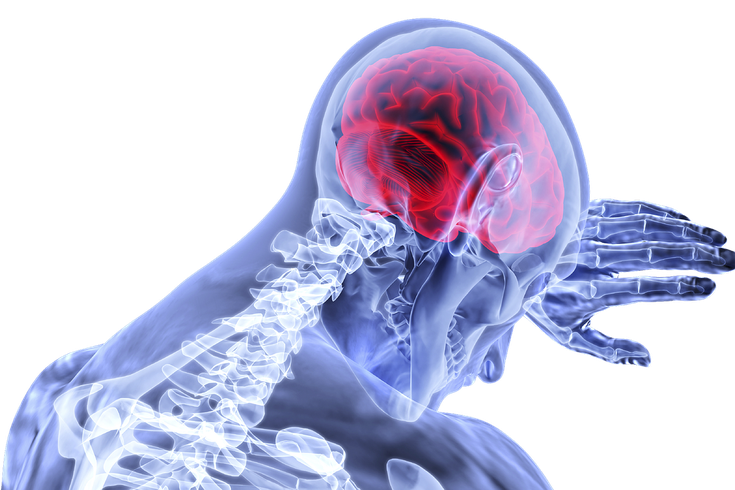

Because of reports indicating the coronavirus may be able to attack the brain, the CDC has added 'new confusion or inability to arouse" to its list of COVID-19 emergency warning signs.

As doctors gain a better understanding of how the coronavirus attacks the human body, the list of possible symptoms caused by an infection continues to grow. It now appears to include neurological damage.

Reports from China, where the pandemic originated, and other coronavirus hotspots, including the United States, suggest that the coronavirus can spread to the brain, potentially leading to a seizure, stroke or encephalitis.

In response, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has added "new confusion or inability to arouse" to the list of emergency warning signs for COVID-19.

The most common symptoms are cough, fever, fatigue and difficulty breathing. Other COVID-19 patients have experienced headache, vomiting, nausea and loss of sense of smell and taste.

But there is growing concern about the coronavirus's ability to harm the brain.

According to Dr. Lin Mei, director of the Cleveland and Brain Health Initiative, the coronavirus can travel to the brain from the nasal cavity, through the bloodstream or by attaching itself to nerve terminals.

More research is needed to determine whether the coronavirus directly causes neurological symptoms by breaching the blood-brain barrier or if those symptoms are a side effect of the virus attacking other systems in the body.

For instance, does the coronavirus directly cause a stroke or does the infection lead to a spike in blood pressure, which then triggers a stroke?

Henry Ford Health System doctors recently reported a case of encephalitis in a 58-year-old Detroit woman who tested positive for COVID-19. She developed acute necrotizing encephalitis, a central nervous system infection more commonly seen in young children.

Her symptoms began with just a fever, cough and muscle aches. But a few days later, she started experiencing confusion and disorientation. She was rushed to the emergency department by ambulance and was tested for the flu and COVID-19. The flu test came back negative, the rapid COVID-19 test positive.

Her care team suspected she had encephalitis and ordered imaging scans. The MRI scan showed abnormal lesions in both the thalami and temporal lobes of the brain, which regulate consciousness, sensation and memory function.

"This is significant for all providers to be aware of and looking out for in patients who present with an altered level of consciousness," Dr. Elissa Fory, a Henry Ford neurologist said in a statement. "We need to be thinking of how we're going to incorporate patients with severe neurological disease into our treatment paradigm. This complication is as devastating as severe lung disease."

Frank Carter, a 82-year-old man in Tennessee, also experienced neurological symptoms related to COVID-19, NBC News reported. Besides some nausea and vomiting, the first indicator of the infection was delirium, according to his daughter, who is a nurse. He died within a week.

There have been neurological symptoms in COVID-19 patients in China as well.

At the Union Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, 36.4% of COVID-19 patients developed neurological issues, according to a study published in the journal JAMA Neurology. For some, the neurological symptoms even showed up before the cough and fever.

"We've been telling people that the major complications of this new disease are pulmonary, but it appears there are a fair number of neurological complications that patients and their physicians should be aware of," Dr. Andrew Josephson, editor of JAMA Neurology, wrote in a commentary to the study.

Dr. E. Wesley Ely, a professor of medicine and critical care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center is collaborating with the Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction and Survivorship Center in studying post-mortem brain tissue to better understand how COVID-19 affects the neurological system.

The researchers will measure different regions of the brain to see whether they have shrunk. They also will look for damage to neurons and evidence of the proteins associated with dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Carter's brain was the first to be donated to the project.

Health officials say that it is important for people to watch for sudden cognitive changes in family members so they can more quickly get the help they might need.