September 04, 2015

Photo courtesy/Kramer + Marks Architects, Ambler

Photo courtesy/Kramer + Marks Architects, Ambler

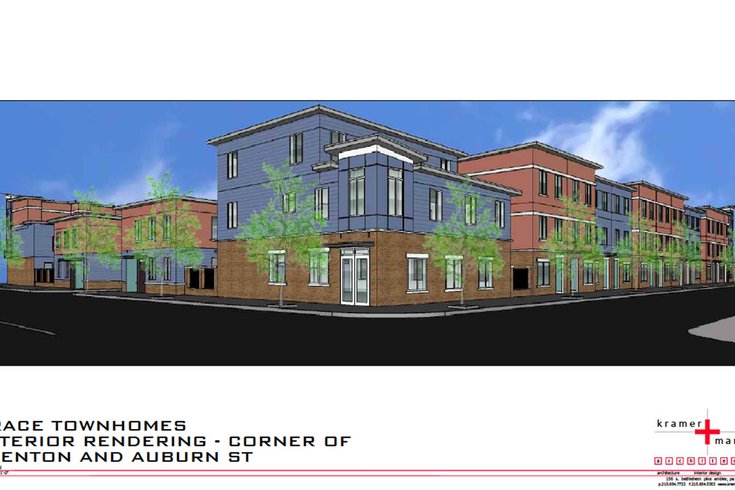

A rendering of the Grace Townhomes project on Auburn Street between Tulip and Aramingo in Kensington. The Women's Community Revitalization Project will break ground today on land owned by the Community Justice Land Trust.

Kensington has long been a byword for deindustrialization and blight. But today there are visible changes in the neighborhood.

Standing at Front and Oxford streets, below the windows of the Women’s Community Revitalization Project’s (WCRP) headquarters, three separate infill housing projects are visible.

The building that houses the community group is itself a testament to the neighborhood’s draw for new residents. Back in the day, Oxford Mills housed a dye works for the city’s once-powerful textile industry. Today it has been re-purposed into a mixed use residential and office building (“Philadelphia’s Urban Oasis”) – complete with an upscale coffee shop.

“When I came here I didn’t foresee this happening to this neighborhood,” says Nora Lichtash, executive director of WCRP, who has worked in Kensington since 1978. “In 2001, most real estate transferred for $40,000 or less, then by 2008 almost nothing transferred for $40,000.”

The changing real estate prices in Kensington reflect pressures from Northern Liberties, Fishtown and Temple student housing, she said.

“[WRCP] leased a space on Fairmount Avenue for 17 years and then got displaced by high-end residential," she said. “But we support development occurring in our neighborhoods, it’s just the displacement that’s a problem.”

The organization is turning to a new strategy to help ensure affordable housing in its target neighborhoods: community land trusts.

It's a relatively simple concept that has been gaining currency in affordable housing circles in recent years. In such an arrangement, a non-profit or governmental body obtains land, then builds (or allows others to build) housing or some other community-approved use on it. But the land trust retains control of the underlying land and ensures, often through a 99-year ground lease, that whatever sits on it will remain affordable and under community control in perpetuity.

Community trusts, however, are incredibly difficult to pull off, specifically the labor and resource intensive tasks of land acquisition and property maintenance. An organization without political sophistication, professional expertise and adequate funding can find itself easily outmatched.

But WCRP’s plan for a community land trust have been unfolding over the past five years, and it already owns and manages 250 units of housing with a staff of 20.

Today, it will break ground on land owned by the Community Justice Land Trust for 36 units of housing on Auburn Street between Tulip Street and Aramingo Avenue in Kensington. Units in the Grace Townhomes development will be available as rental housing with an option for purchase by eligible tenants in 15 years. WCRP hopes to help those families earning between $40,000 and $58,000 buy their homes, with the goal of starting housing counseling at the eight-year mark of residency – assuming they are eligible for mortgages.

“If there is any group that is going to pull this off, it’s going to be WCRP,” says John Davis, a consultant with Burlington Associates, a Vermont firm that helps non-profits establish land trusts and is aiding WCRP in its efforts. He notes that some land trusts have de-emphasized the importance of community control after they actually start the hard work of buying and developing land. “What gives me confidence about WCRP is that for over 28 years they have already been very successful at keeping the C in community development.”

Despite WCRP’s pedigree, its efforts have been met with skepticism. For those who’ve been around for a while, the term community land trust does not evoke cheery memories in Philadelphia.

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, when the trusts were first being established in cities, Kensington was home to a couple of the original urban experiments. The results ranged from unimpressive to disastrous.

In the 1980s, the Kensington Joint Action Council – a radical group that utilized direct action tactics and squatting – formed a land trust to combat fears of gentrification. The fledgling Latino advocacy group, Manos Unidas, formed a land trust around the same time. Both organizations lacked the necessary financial sophistication and political wherewithal, and funding proved to be a problem – especially because they acquired dilapidated buildings for rent or sale to low-income residents. Neither land trust is still in existence.

“I don’t know if the land trust ever had any full-time paid staff, and at some point they just kind of let it go,” says Markita Morris-Louis, a lawyer who in 2011 led the unraveling of the mess Manos Unidas left behind.

The homeowners “were paying taxes on the developed portion but the tax notices for the underlying land were going to the land trust. They were going nowhere,” she said. “There were unpaid taxes going back years. And some of the [properties] had tax liens as a result. They didn’t understand the land trust structure and they were surprised to find out [that the land trust owned the land beneath their homes].”

WCRP is aware of that less-than-positive history, with one former Manos Unidas employee on staff and another who was a homeowner on the defunct trust.

“When you research why some CLTs go out of business and why some nonprofits go out of the business, it’s often some of the same things,” Lichtash says. “It isn’t necessarily connected to the values or mission of a CLT. It’s just that you can make these mistakes if you are undercapitalized or when the economy changes.”

Davis insists that the community land trust model has improved since the 1980s. Today there are at least 280 community land trusts across America, and total collapses like the one experienced by Manos Unidas are rare.

WCRP’s land trust has an oversight board with members ranging from low-income tenants to an executive with TD Bank, a diversity of views meant to ensure accountability.

WCRP also hopes to develop 35 additional units of affordable, rent-to-purchase housing on the land trust, a project that has already cleared necessary zoning hurdles and secured some funding from the city. But more money from state and federal sources will be needed to begin construction. WCRP also hopes to move some of its existing housing, and the land that it sits on, into the trust in the near future.

While focused on building on vacant land, WCRP’s one foray into rehabilitating dilapidated buildings ended badly. An effort to bring a deteriorated, former bank building on Front and Norris streets into the land trust’s fold was foiled, according to Lichtash, by NIMBYism from new residents of the neighborhood. Opponents were ready to drag a zoning battle out for years and WCRP surrendered. The property has now been taken over by a private developer, Onion Flats.