May 26, 2023

Source/Image licensed from Ingram Image

Source/Image licensed from Ingram Image

New research suggests people with chronic pain have unique brain activities linked to their perceptions of pain. This finding may lead to the development implanted devices that are able to predict and disrupt pain signals in the brain. The photo illustration above shows a man suffering from knee pain.

One in five American adults suffers from chronic pain, which is defined as persistent pain that lasts more than three months and recurs despite treatment. The prevalence of chronic pain and the difficulty of treating it has spurred substantial research.

A new study of brain signals in those experiencing chronic nerve pain has revealed clues about the specific pathways activated by pain. The research is the first of its kind to precisely monitor chronic pain while it's felt, and it could lead to the development of brain implants capable of predicting and disrupting pain.

The study followed four people whose shoulders and brains were implanted with electrodes that measure activity over a period of several months. Three of them had pain stemming from a stroke, while the other had phantom-limb pain following a leg amputation.

The four volunteers reported their own perceptions of pain multiple times a day as brain signal data were collected from the implants. That information was then analyzed to recognize patterns.

Researchers found that their experiences of chronic pain were linked to the orbitofrontal cortex, an area of the brain associated with emotional regulation, self-evaluation and decision-making.

"Every patient actually had a different fingerprint for their pain," Prasad Shirvalkar, lead author of the study, told The New York Times.

The study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, could provide a way to objectively measure brain activity that corresponds to self-reported chronic pain. Using subjective reports of pain levels has long been the standard of chronic pain evaluation, but it often results in frustration for patients and physicians; circumstances that cause chronic pain flares may not be present during office visits, and they may be hard to communicate in ways that support medical assessments.

Although past brain imaging studies have looked at blood flows to try to understand chronic pain, these experiments were less precise and required patients to come to labs. While helpful in identifying the areas of the brain most relevant to chronic pain, these methods have been less direct and long-term than tracking patients as they go about their daily routines. The volunteers in the new study pressed buttons to activate the implants and record data for 30-second periods when they were feeling pain.

"When you think about it, pain is one of the most fundamental experiences an organism can have," Shirvalkar said. "Despite this, there is still so much we don't understand about how pain works. By developing better tools to study and potentially affect pain responses in the brain, we hope to provide options to people living with chronic pain conditions."

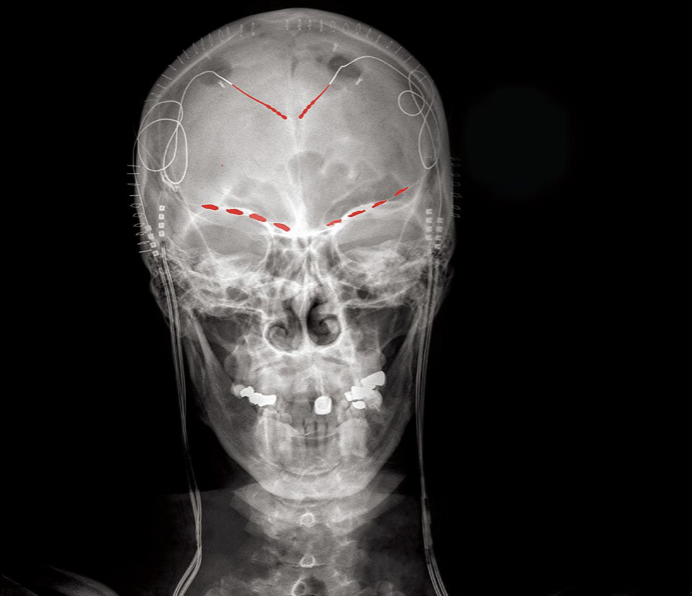

The X-ray above shows electrodes implanted in the brain of a patient with chronic pain. A new study suggests chronic pain is linked to brain activity that varies based on the individual.

Notably, the study also looked at the ways the volunteers responded to acute pain, which usually stems from a recent issue that is expected to heal with time and treatment. Heat was applied to the participants' bodies to induce pain responses. In two of the patients, the implants recorded brain activity that was limited to another area of the brain, the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with both chronic and acute pain. The study suggests that the brain may process chronic and acute pain differently.

The study's small size and its specific focus on nerve pain mean more research is necessary to observe how different kinds of chronic pain appear in the brain, and whether the implants are effective at predicting their signatures in individual patients. It could form the basis of future chronic pain treatments that use deep brain stimulation, including the possibility of implanted devices that cut off the signals associated with chronic pain.

A larger goal of the study is to find non-addictive pain treatments, unlike opioids, whose risks have fueled a wider public health crisis. Other daily medications used to treat chronic pain also have drawbacks for patients, such as short-term side effects and health problems linked to long-term use.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study as part of its wider BRAIN and HEAL initiatives, which support ongoing research into the brain, technology development and addiction treatment.

Source/National Institutes of Health

Source/National Institutes of Health