May 08, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

William Penn envisioned Centre Square as the center of Philadelphia, complete with a meeting house, a marketplace and a state house. His plan never fully came to fruition but City Hall today is the center of Philadelphia government. This is a view of City Hall and Dilworth Park from the Residences at the Ritz-Carlton.

William Penn originally intended Centre Square to serve as the center point of Philadelphia.

While his four other squares were set away as green spaces, Penn envisioned Centre Square as location for a Quaker meeting house, a marketplace and a state house.

City Hall has stood on Centre Square for more than a century, its 548-foot tower visible throughout much of the city.

But Penn's vision for the space, later known as Penn Square, never really came to fruition. In reality, it would take two centuries for an government building to occupy Centre Square.

A Quaker meeting house was indeed constructed on the southwest corner of Centre Square in 1685, according to 19th century historian John Fanning Watson. But Philadelphia didn't develop as Penn expected, with two thriving waterfronts linked by a public center for government and commerce.

Instead, development surged along the Delaware River, where settlers quickly established centers for commerce and government. Centre Square mostly remained in its natural state — a forest of oak and hickory trees where Philadelphia residents spotted deer and turkey — well into the 18th century.

The Quaker meeting house, located far from the action, initially was used for day meetings. Another meeting house, near Front and Mulberry (now Arch) streets, was used at night. But being so far away, the Centre Square meeting house eventually became deserted.

The state house and market place never were constructed, at least not as Penn envisioned.

Until the American Revolution, Centre Square served as the starting point for horse races, with a pathway heading out to the Schuylkill River.

Much of the area west of Broad Street remained wooded until the Revolution. Known as Centre Woods, the area was part of the proprietary's estate. A man named Adam Poth cared for the woods. But they were cut down and sold to the British when the redcoats captured the city during the American Revolution.

Once Centre Square was cleared, it served as a military training space and an execution grounds.

Centre Square played a minor role in one of Philadelphia's early murder cases.

A British officer in the Royal American regiment, Lt. Bruluman, sought to end his life during Philadelphia's colonial days. But he did not want to commit suicide. Rather, he decided to commit a crime that would result in his execution.

Bruluman "soured by some disgust, or perhaps insane, was weary of life," according to Henry Simpson's account in "The Lives of Eminent Philadelphians, Now Deceased."

And so, on Sept. 4, 1760, Bruluman set out to kill the first person he encountered.

Carrying a musket, the soldier headed for Centre Square, where he encountered a doctor, Thomas Cadwalader, who bowed and greeted Bruluman warmly. Though Cadwalader was a stranger, he decided he could not kill him, due to his kind manners, Simpson wrote.

But Bruluman was committed to killing someone. He headed for a tavern not far from Centre Square, where he drank liquor before heading upstairs into the billiards room.

There, Bruluman observed Robert Scull playing billiards with several other men, according to the "New Newgate Calendar: Being Interesting Memories of Notorious Characters."

As Scull hit a ball into one of the pockets, Bruluman said "Sir, you are a good marksman, now I'll show you a fine stroke." He then fired two musket balls into Scull's body.

"Sir, I have no malice or ill will against you;" Bruluman reportedly said. "I never saw you before, but I was determined to kill somebody, that I might be hanged, and you happen to be the man; and I am very sorry for your misfortune."

Before he died, Scull said he forgave his shooter and asked that Bruluman's life be spared. It was not. Bruluman was executed.

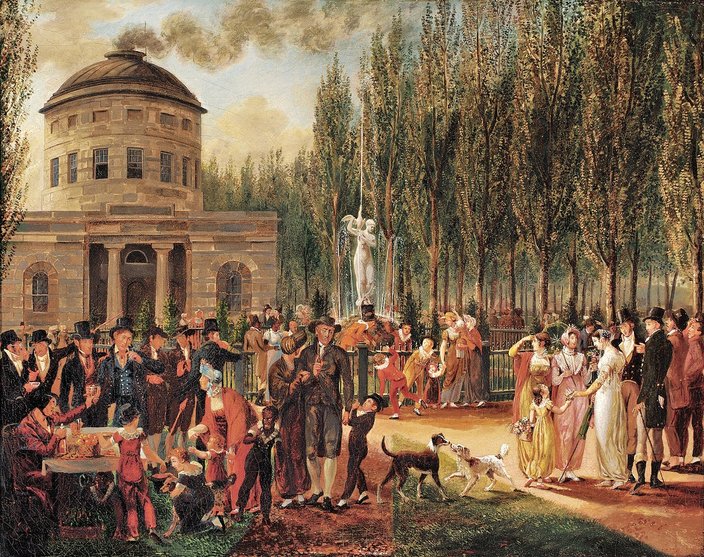

Philadelphia residents celebrate July 4 near the Centre Square Pump House, as painted by John Lewis Krimmel, by 1812.

The Fairmount Water Works, located along the edge of the Schuylkill River, stands as a National Historic Landmark where people now host wedding receptions and dinners.

But its predecessor was located in Centre Square.

Designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Centre Square Pump House combined a classical appearance with a functional structure.

Latrobe, who later oversaw construction of the U.S. Capitol, served as the architect for the project. But he hired an engineer, Frederick Graff, to assist him with the design, an atypical decision at the time. It was built in 1799.

Through a series of pumps, it brought water from the Schuylkill River before distributing clean water through wooden pipes to water hydrants and subscribers.

Yet, due to its unreliable steam engines, the Pump House had a relatively short lifespan. In 1815, the city opened Fairmount Water Works, but continued using the Pump House as a distribution point for another 17 years.

The Pump House remained standing until 1829.

The City Hall tower as seen from the inner courtyard.

By the early decades of the 19th century, it became clear that Philadelphia needed a new city hall building.

The County Commissioners announced in January 1838 that they wanted to move to Penn Square, but only if the city's two legislative bodies — the councils of select and common — would move, too.

Thus started a debate that would continue, off and on, for another three decades.

Should the city move its offices to Penn Square, the site William Penn originally had intended as the center of the city? Or should they remain somewhere on Independence Square, which had taken on its own historical heritage?

"It's excessively large, it's excessively ornate and it's excessively white. The truth of it is that it's made out of bricks." – Kenneth Finkel, Temple University history professor, on City Hall

Though the construction trades favored the initial proposal, many city leaders opposed it primarily because the city's downtown still revolved around the Delaware River.

By 1854, the times had changed. The city's population had pushed westward toward the Schuylkill River. The city and county governments had consolidated, effectively increasing the size of government and exacerbating the space issues that initially prompted proposals to relocate.

Beginning in 1858 and extending through 1870, various proposals would be introduced by either the Council of Select or the Council of Common.

Proponents of Penn Square included residents who lived in the city's western wards. Bringing the city's offices to a more centralized location would ease their travel when it came time to pay their taxes, water and gas bills — which needed to be done in person.

Those who favored Independence Square included the lawyers who frequented the city's courts and whose offices were located nearby. Others feared that property values would decline if the city's public buildings moved elsewhere.

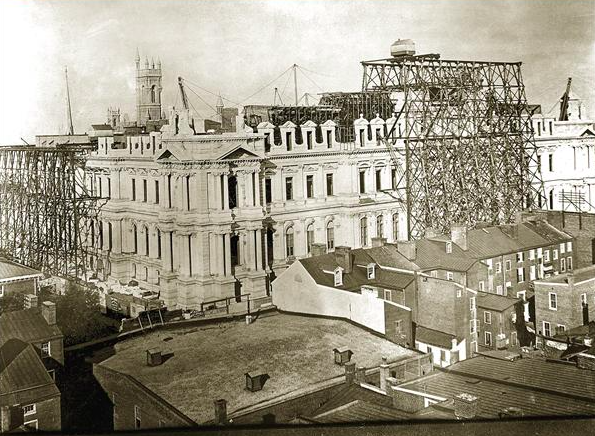

This photograph shows Centre Square before construction began on Philadelphia's City Hall in 1871.

Throughout the debate, architect John McArthur drew up designs for each location. His designs for Independence Square included a horseshoe-shaped building in Victorian style, with wings extending to Independence Hall. For Penn Square, McArthur initially designed a pair of U-shaped classical buildings, one with a dome and another with a steeple.

But the debate stalled in the legislature. The select council, a body based on equal representation, preferred Independence Square. The common council, based on population, favored Penn Square.

At one point, a proposal was floated to build a cultural institution on Penn Square similar to the British Museum in London. The bill permitted the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Academy of Fine Arts and the Franklin Institute, among others to build on Penn Square. Eventually, such a cultural center popped up around Logan Square.

The debate finally came to a close in October 1870, when state legislators authorized a referendum allowing the city's residents to settle the matter. But Independence Square was no longer an option. City officials had been lobbying Washington for the 1876 Centennial Exposition and figured digging up Independence Square would have a negative impact.

Instead, voters chose between Penn Square and Washington Square, though some expressed concerns with building on the latter, where thousands of Revolutionary War soldiers and Yellow Fever victims are buried.

Penn Square easily won the resolution by a vote of 51,625 to 32,825. The vote largely split on population, with the more populated western wards favoring Penn Square.

City Hall, as viewed from the southwest corner, was under construction in 1881. It already had been under construction for 10 years, but would not be completed for another 20 years.

Finally approved, construction of City Hall began in 1871. But the new government building would not be finished for 30 years.

By the time the $24 million structure opened in 1901, the architecture had fallen out of style.

There was a large appetite for massive, public buildings in the late 19th century, said Kenneth Finkel, a Temple University professor in American Studies who also writes for PhillyHistory.org. City Hall was designed in the Second Empire style made popular by the French.

"It's only in the last few decades that people have decided they truly love it. The Victorian excess has actually been perceived as beautiful." – Kenneth Finkel

But by the turn of the century, Philadelphia had more than 100,000 brick rowhouses, mostly two or three stories tall. City Hall, with its white marble and 548-foot tower, was unlike anything else in Philadelphia. It was the world's tallest building, though it was later surpassed during construction by the Washington Monument and the Eiffel Tower. (With its nearly 700 rooms today, City Hall remains the largest municipal building in the nation and the tallest masonry building in the world.)

It was terribly unpopular when it was finished, Finkel said.

"It's excessively large, it's excessively ornate and it's excessively white," Finkel said. "The truth of it is that it's made out of bricks. Under the skin of white marble, there's red bricks inside - that's what holds them up. It is the ultimate red brick building – but you wouldn't know it."

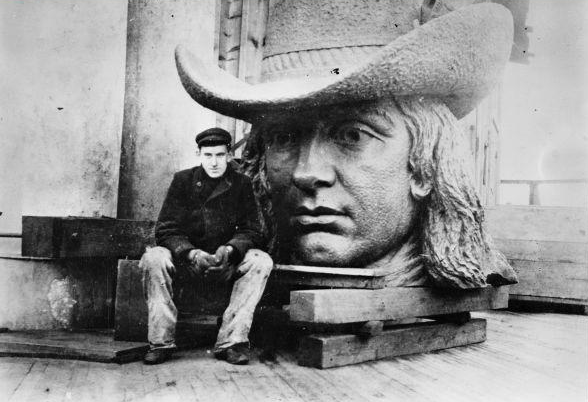

City Hall includes more than 250 marble figures, heads and allegories sculpted by Alexander Milne Calder and others. It is topped by a 37-foot-tall bronze statue of Philadelphia founder William Penn, who may have been more rotund than his sculpture suggests.

"They kept tweaking him until he looked more like their idea of the handsome founder, instead of the real figure," Finkel said. "He loses his double chin and the ruffles get more prominent."

The William Penn sculpture atop City Hall was assembled in several different parts.

In some ways, Finkel said, City Hall evokes Independence Hall – but dressed up in 19th century style. Both buildings include setback towers that face toward the north. And City Hall's corner towers echo the corner buildings built on Independence Square.

Yet, perhaps the only reason that City Hall survived was because it would cost millions of dollars to demolish. Stretching into the 1950s, city officials considered tearing down City Hall at various points. But doing so would prove cost-prohibitive.

"It's only in the last few decades that people have decided they truly love it," Finkel said. "The Victorian excess has actually been perceived as beautiful."

City Hall became a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

That attitude became evident in the early 1980s, when developer Willard Rouse proposed building taller than Penn's statue atop City Hall. For nearly 100 years, by gentleman's agreement, the Penn statue had marked the highest point in Philadelphia.

The construction of One Liberty Place – the first building to break the so-called height barrier — prompted considerable outcry and, perhaps, a curse on the city's professional sports. The city went 25 years without a winning a major championship until the Phillies won the World Series in 2008.

In between, Penn's statue was twice adorned with sports gear. Penn wore a Phillies cap in 1993 and a Flyers jersey in 1997.

As temperatures begin to rise, the fountains in Dilworth Park on the west side of City Hall become a popular way to cool down.

In recent years, the city sought to transform Dilworth Plaza, a multi-level, concrete space located on the western edge of City Hall into a small park.

The city spent $55 million to renovate the plaza, reopening it in 2014 as Dilworth Park. The space now includes an interactive fountain, a grass lawn, tree grove and seating areas. In the winter, an ice rink offers residents an opportunity to skate.

The space has hosted a surprise concert by Stevie Wonder and the Villanova men's basketball team's NCAA title celebration.

Source/Public Domain

Source/Public Domain Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice