April 10, 2016

Source/Camden County Police Department Facebook

Source/Camden County Police Department Facebook

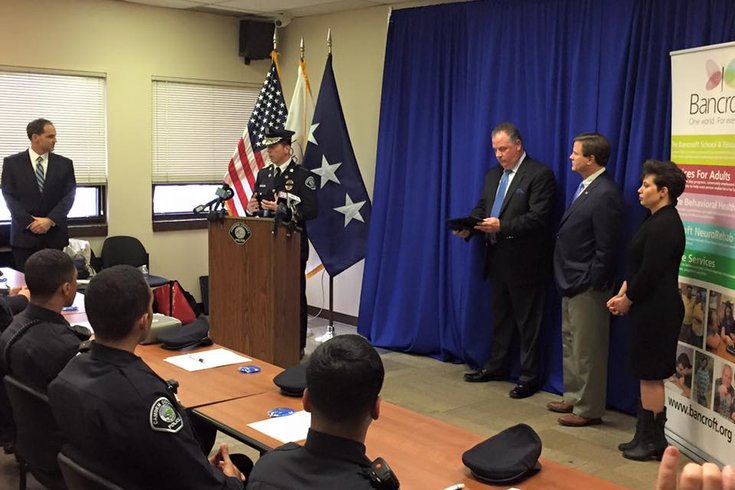

Camden County Police Chief J. Scott Thomson speaks with officers during an autism sensitivity training session.

Imagine a scenario where police are searching for a man who just committed an armed robbery. They meet a man who seems to fit the description, and he's behaving suspiciously: avoiding eye contact, refusing to speak, ignoring officers' commands.

He could be a suspect — or he could be an innocent man with autism.

Police officers must rely on their training to make sure that situations like the one above don't end with someone getting hurt. That's why over 200 Camden County police officers on Friday attended an autism sensitivity training session held by Bancroft, a local nonprofit organization that serves people with developmental or intellectual disabilities.

Officers may think that "people with autism or intellectual disabilities are being disobedient or disrespectful to police, when in reality they're having trouble communicating," explained Karent Parenti, Bancroft's Vice President of Community Solutions.

"We ask them to take a good 15 seconds to assess the situation," she said.

The officers learned the basics of what autism spectrum disorder is and how to recognize the associated behaviors, such as avoiding eye contact, repetitive actions or aversion to loud noises. If the person is upset, they may start yelling or injuring themselves, without being able to say what's wrong.

"The police have to work directly with the public, so it's very important they know how to work with different individuals who have different needs," said Freeholder Carmen Rodriguez.

Lt. Kevin Lutz said the training helped him realize "there may have been times that I encountered someone with autism and maybe not been aware."

Next, the officers learned how to de-escalate the situation. The main takeaway: stay calm.

"If we overreact, it can make things much, much worse on their end from their reaction as well," said Lutz. "The calmer we are, the calmer they're going to be."

That kind of training could help New Jersey officers avoid a tragedy like what happened in Maryland, when a man with Down's Syndrome died under police restraint after he refused to leave a movie theater.

Presenters at Friday's training session recommended that officers redirect the person's attention to another activity if possible. Officers must carefully monitor their language, tone and gestures.

"You have to have a very calm approach. Ask them very non-judgmental questions, how can you help them. Be empathetic," said Lutz.

The police department also received decals that they can give out to the public. Caretakers can voluntarily stick the decals to a window if they want to let law enforcement or first responders know that a member of the household has a developmental disorder.

Bancroft is planning 15 more training sessions in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware over the next year.

In a separate effort, three universities — Drexel, Penn State Hershey and the University of Pittsburgh — have been collaborating with Pennsylvania's Bureau of Autism Services to provide training and other autism-related resources to different types of first responders, including firefighters and EMTs.

In New Jersey, where 1 out of 41 children has been diagnosed with autism, it's more important than ever for law enforcement to understand what being "on the spectrum" means.