February 24, 2020

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

In an effort to combat the opioid crisis, several Philadelphia health systems have committed to ensuring that their primary care physicians undergo training necessary to prescribe buprenorphine, a drug commonly used in medication-assisted treatment.

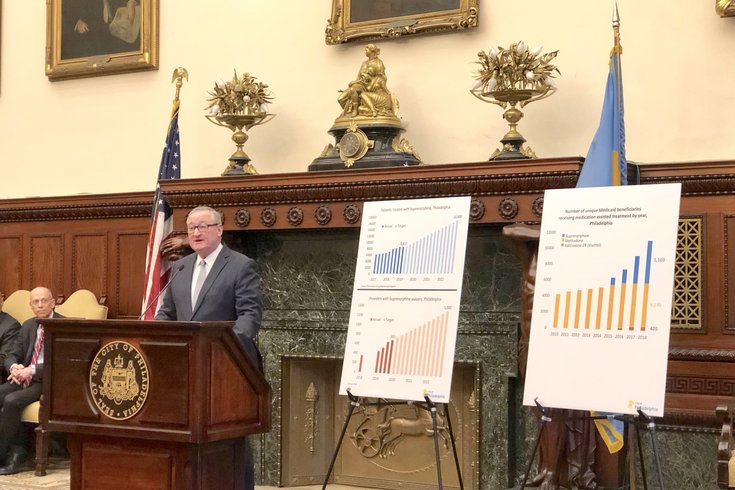

Philadelphia health officials are seeking to combat the worst opioid crisis in the United States by drastically increasing access to buprenorphine, a drug commonly used as part of medication-assisted treatment.

Addiction treatment specialists have served as the primary access point to the drug. That's partly because, in order to prescribe it, medical providers must undergo specialized training and receive a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency.

But city health officials are pushing to increase the number of primary care practitioners who are able to prescribe buprenorphine – and local health systems are responding. It's a development that Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley called a "major step forward."

"Treatment for a long time has been relegated to these special drug treatment programs," Farley said Monday. "Let me be clear: We desperately need those specialized drug treatment programs. They're a key part of our overall response.

"But some people prefer to get treatment through their regular doctor. Unfortunately, today, not enough providers can write prescriptions for buprenorphine-medication-assisted treatment."

Last year, only 691 medical providers that could prescribe buprenorphine, also sold under the brand name Suboxone. But only about 215 were primary care physicians – a total that represents less than 20% of all PCPs in Philadelphia.

By 2022, city officials want 1,300 medical providers to have prescribing power.

To do so, Jefferson Health is committing to ensure that all of its 319 adult primary care providers, including more than 100 in Philadelphia, have prescribing power by the end of the 2020.

Temple University Health System is doing likewise with its 110 PCPs. So too is Penn Medicine, the Einstein Healthcare Network and the city's health department.

Those commitments will increase the city's buprenorphine prescribers by about 400. Each of the health systems has committed to funding the 8-hour training course for its providers.

City officials said they are not aware of any other health systems in the United States that have committed to making all of their primary care providers buprenorphine prescribers, Farley said.

"In the future it will be the norm that if you need treatment for opioid addiction you can get it from your regular doctor," Farley said, comparing it to treatment for diabetes and high blood pressure.

Buprenorphine helps people resist the cravings to revert to opioids like heroin and prescription painkillers. It is one of three drugs federally-approved to be used as part of medication-assisted treatment, which combines behavioral therapy with medication.

The drug reduces the likelihood of a patient suffering a fatal overdose by 50%, Farley said.

City officials have made medication-assisted treatment a key strategy in reducing addiction and overdose deaths. Last year, the health department launched a media campaign touting its benefits.

"It's one of the most fruitful endeavors a physician can do," said Dr. Rohit Gulati, Einstein's chief medical officer. "Many of my patients were able to lead productive, normal lives off of Suboxone. ... The amount (of people) that we need to treat is extraordinary and that is why the entire community is here to treat it."

The length of time a patient requires buprenorphine differs. Some may only take it for several months, while others will use it for years. But doctors tout its power to prevent overdose deaths.

Dr. David Horowitz, Penn Medicine's associate chief medical officer, recalled the transformation a patient had after receiving the drug after being admitted into a West Philly hospital 18 months ago. At the time, she was resistant to medical care while she was suffering withdraw.

"Within a few days, she becomes the person that she probably was before she developed her addiction," Horowitz said. "She's interactive. She's pleasant. She's disclosing about the struggles in her life. She is apologetic for her prior behavior but also grateful for the fresh (start)."

The city health department also is establishing a clinical consultation line, available 24/7, for doctors seeking prescribing advice.

Follow John & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @WriterJohnKopp | @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Add John's RSS feed to your feed reader

Have a news tip? Let us know.