August 20, 2019

Fatma Deniz/University of California, Berkeley

Fatma Deniz/University of California, Berkeley

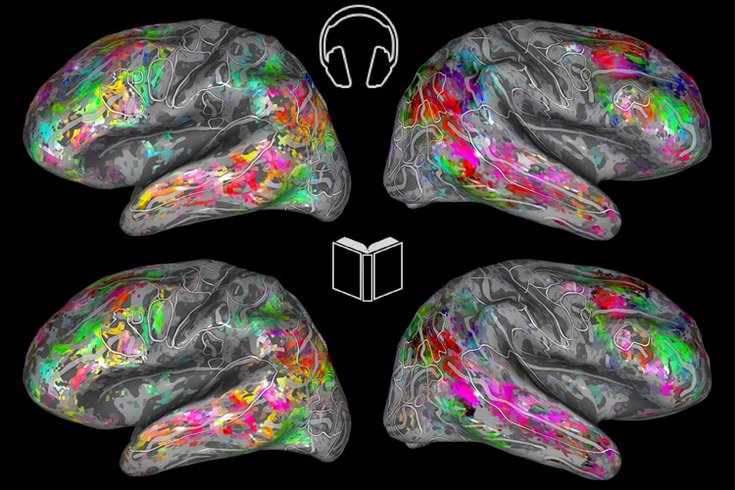

These color-coded maps display the way the brain processes the meaning of words when listening to an audiobook (top) and when reading a book (bottom). Researchers have found the process to be essentially the same.

Do you prefer to find a cozy setting to sit down and read for awhile? Or are you the type that would rather pop on an audio book during a lengthy drive or aerobic workout?

Either way, the same cognitive and emotional areas of your brain are being activated, researchers have found.

Neuroscientists at the University of California, Berkeley created interactive maps that can predict the brain areas activated by different word categories. For instance, words associated with numbers stimulate one area while words related to locations activate another.

The intake of those words – whether by reading or listening – makes virtually no difference in how the brain processes the semantics. This understanding could could open the door to helping people with learning disorders, like dyslexia, researchers say.

"We knew that a few brain regions were activated similarly when you hear a word and read the same word," postdoctoral researcher Fatma Deniz said in a statement. "But I was not expecting such strong similarities in the meaning representation across a large network of brain regions in both of these sensory modalities."

Scientists had nine people listen to stories from a podcast series, "The Moth Radio Hour," as they scanned their brains using a functional MRI to determine the areas stimulated by words. They later repeated the exercise with people reading the same stories.

The scientists then created interactive, three-dimensional maps of both datasets. They used color codes to identify the areas of the brain activated by varying word categories, including emotional, social and mental associations.

They found the maps to be nearly identical. And they enabled researchers to predict the areas of the brain that a word would activate.

The maps could help researchers develop new interventions for dyslexia, a language-processing disorder that affects reading.

“If, in the future, we find that the dyslexic brain has rich semantic language representation when listening to an audiobook or other recording, that could bring more audio materials into the classroom,” Deniz said.

Similarly, the maps could spur new interventions for people with auditory processing disorders. They also potentially could be used to compare the language processing of healthy people to those who are suffering from a brain injury, stroke or epilepsy.

The findings were published Monday in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Follow John & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @WriterJohnKopp | @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Add John's RSS feed to your feed reader

Have a news tip? Let us know.