The following is an excerpt from "Target: The Senator – A Story About Power and Abuse of Power," written by Ralph Cipriano and published in November.

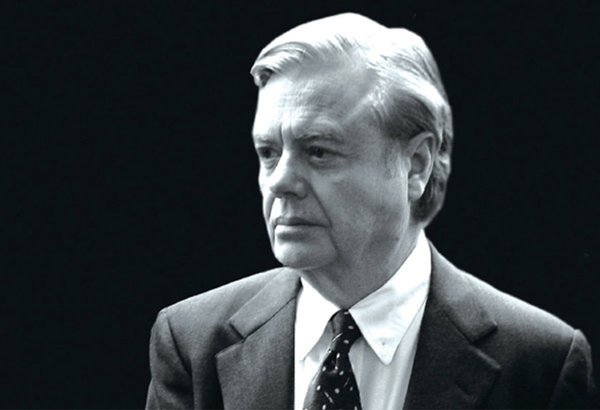

The book tells the story of former Pennsylvania state Sen. Vincent J. Fumo, "a master politician who reigned for a generation over Philadelphia and the state capitol of Harrisburg, cutting deals and red tape, and bringing in billions of dollars for his constituents," according to a cover teaser.

Q&A WITH VINCE FUMO: I didn't deserve 'the scarlet letter F'

Convicted of 137 counts of corruption in 2009, Fumo did his time in federal prison and kept a low profile, granting no interviews until those for the book. (He has subsequently sat down for an interview with PhillyVoice.)

The book is available now from Amazon.com as a Kindle edition and will be available in paperback soon.

• • •

DINNER WITH THE PRESIDENT

His dark, pinstriped, two-button suit with wide lapels was custom-made by Benny, his South Philly tailor. His white Turnbull & Asser oxford shirt was topped off by a red silk tie from Robert Talbott.

Around his waist, he wore a Tiffany belt with a gold buckle engraved with the initials VJF. His feet were clad in John Lobb custom-made shoes. On his hands and wrists, he sported a gold Rolex Presidential watch, Van Cleef & Arpel cufflinks, and the official gold ring of the Pennsylvania Senate.

On the night of October 2, 1998, Vince Fumo was going to a party.

The 55-year-old senator was clean-shaven and his bushy salt-and-pepper hair neatly coifed. He was riding in the back seat of a chauffeur-driven black Cadillac with the license plate “PA-1,” referring to Pennsylvania’s First Senate District.

When the Caddy pulled up to the VIP entrance at Philadelphia City Hall, police escorted the senator through an overflow crowd that included demonstrators, television crews, and Secret Service agents. Inside the elaborate Second Empire monolith that is the largest municipal building in the country, with 700 rooms, the senator rode the elevator to the second floor.

As he surveyed the scene, Fumo wasn’t in any hurry to greet the President, who probably wouldn’t remember him. The senator may have been the most powerful politician in Pennsylvania, but he didn’t have a national reputation. When Clinton first campaigned in Philadelphia as a presidential candidate in 1992, he had to ask U.S. Representative Robert Brady, “What’s a Fumo?” (Brady, in an interview, said he told the President, “Don’t worry, he’ll be here in a few minutes to bust your balls.”)

On the night of the presidential fund-raiser, another congressman, Robert A. Borski Jr., a Democrat from Philadelphia, described Fumo to the guest of honor by saying, “Besides you, Mr. President,” the senator might be “the best politician in the room.”

Borski wasn’t bragging. As Clinton would soon discover, when it came to playing politics on his home turf, not even a sitting U.S. president could trump the senator.

It had seemed like a coup when Rendell got the President to agree to headline the local fund-raiser for the Democratic National Committee. Then, a bomb went off.

Just two months before he came to Philadelphia, Clinton had gone on television to confess an inappropriate relationship with a twenty-four-year-old White House intern named Monica Lewinsky.

Back in Washington, Republicans in Congress were talking about impeachment. But in the Democratic stronghold of Philadelphia, Rendell was determined to show the President some blue state love, plus a half-million dollars in fresh campaign cash.

Fumo, however, was no fan of Clinton’s. The senator had watched in dismay as the President had taken one political position after another that he disapproved of. As a politician, Fumo couldn’t easily be pigeonholed. When it came to political ideology, he was all over the lot.

“Let me tell you something, Mr. President. I don’t believe in anything you’re doing in Washington. I’m here tonight, spending my own money, simply because I think you’re getting f***ed.”

On gun control, for example, the senator was a proud life-long benefactor member of the National Rifle Association who had a private shooting range in the basement of his mansion. But on social issues, such as gay rights and welfare benefits, Fumo was a classic liberal.

So Fumo got upset when he saw Clinton pushing gun control, waffling on gays in the military, and stealing welfare reform as an issue from the Republicans. To Fumo, the triangulating President “seemed to be flip-flopping any way the wind blew.”

But Fumo, who had a reputation for being blunt and outspoken, hated hypocrites, especially the grandstanding, Bible-thumping kind. Ask Fumo about the Lewinsky scandal, and he’d tell you he was sick and tired of watching a bunch of “holier than thou hypocrite Republican motherf***ers” lead a moral crusade against the President, all because of “a f***ing blow job.”

“I don’t care how many f***ing blowjobs he gets,” Fumo said. That’s why he wouldn’t accept Rendell’s offer of a freebie to sit at the head table with Ed and Bill. Instead, the senator wrote out a personal check to the DNC for $5,000, to attend the Clinton dinner.

“It was about helping someone when they were down,” Fumo said.

•

The presidential fund-raiser was a choreographed event. On the streets outside City Hall, Rendell had invited local Teamsters to stage a show of support on behalf of Clinton, for the benefit of the TV cameras. Behind metal barriers, 150 men wearing white “Teamsters for Clinton” T-shirts were chanting, “Impeach Ken Starr.”

The independent counsel had just released a 445-page report on the Lewinsky scandal that featured graphic details about multiple “sexual encounters,” a presidential cigar, and a stained dress.

Amid the sea of white-shirted union members, however, about twenty anti-Clinton protesters were straining to be heard. “Impeach Bill Clinton,” they yelled.

One protester, Don Adams, thirty-eight, of Cheltenham Township, Pennsylvania, held up a sign that accused Clinton of being a “liar,” “pervert” and “national shame.”

In a union town like Philadelphia, this was an affront. Rendell had specifically asked the Teamsters to “drown out” the protesters. But for some union members, it wasn’t enough.

A couple of Teamsters walked up behind Adams and ripped the picket sign out of his hands. When Adams turned around, he found himself surrounded by angry union goons.

Welcome to Philadelphia, where politics is a blood sport.

John P. Morris, the crusty boss of Teamsters Local 115, promptly took off his fedora and jammed it on top of Adams’ head, covering the victim’s eyes and temporarily blinding him.

In the practice of union thuggery, this was known as “hatting” a victim, or marking him as a target.

As the TV cameras rolled, several Teamsters rushed the protester, knocking him to the ground, where they repeatedly punched and kicked him in the head.

The police didn’t do anything to stop it. The beating continued even after Adams’s sister, Teri, threw herself on top of her brother, in a vain attempt to protect him.

Adams sustained a concussion, cuts and bruises on his face, and a herniated disc in his neck. His sister was bruised but not seriously injured.

Rendell’s spokesman, Kevin Feeley, further exacerbated the situation by telling reporters, “They [the protesters] chose to make their views known in the faces of Teamsters — that generally is not a good career choice.”

•

Inside City Hall, Clinton and Rendell were oblivious to the street violence as they greeted dinner guests. The room had a capacity of 200. But Fumo noticed that, despite Rendell’s best efforts to pack the place, it was still a small crowd.

The Lewinsky scandal had even Democrats running from Clinton. Philadelphia’s extroverted heavyweight of a mayor, however, remained upbeat. Hey, Vince, Rendell yelled. Come on over and meet the President.

At six foot two, the charismatic President had a couple of inches on Fumo, who, for a career politician, had some unusual quirks. Unlike Clinton and Rendell, Fumo was shy and ill at ease in a crowd, and not much for small talk. But with his fellow politicians, Fumo was notorious for being blunt and profane.

“Mr. President, we’ve met before,” Fumo said, while they shook hands. “You and I rode together in a car.”

Back in 1996, Clinton and Fumo shared a limousine ride to the Philadelphia airport. To jog the President’s memory, Fumo brought up the topic they had discussed during the limo ride: “I supported you in the Pennsylvania primary over Gov. Casey’s urging to the contrary.”

Oh yes, the President said, I remember. But Fumo thought that Clinton was just being polite.

So much for small talk. At $5,000 a plate, Fumo felt free to speak his mind.

“Let me tell you something, Mr. President,” Fumo lectured the leader of the free world. “I don’t believe in anything you’re doing in Washington. I’m here tonight, spending my own money, simply because I think you’re getting f***ed.”

As Fumo watched, Clinton looked surprised, and said, OK, thanks. The two men awkwardly shook hands. Then, Rendell took Clinton around the room to greet more campaign donors. (A spokesman for the Clinton Foundation did not respond to a request for comment.)

As Fumo watched from a distance, the President was holding court with local politicos, some of whom were pointing fingers back at Fumo. Rendell called Fumo over to meet with him and Clinton again, but this time Fumo noticed the mayor wasn’t smiling.

The President’s concerned that you’re holding up two of his judicial appointments, Rendell said. The President was especially concerned about the fate of Legrome D. Davis, a black judge in Philadelphia whom Clinton had nominated to the federal bench, a nominee the mayor also supported.

Fumo may have been just a senator, but he was a master infiltrator and wheeler-dealer who had “his guys” packed onto every city and state board, agency, and commission. His reach extended to the courts, where his handpicked judges sat on benches throughout the commonwealth.

Fumo had even hot-wired a U.S. senator from the opposition party. At Fumo’s request, Senator Rick Santorum, a right-wing Republican, had placed a senatorial hold on Clinton’s two judicial appointments in Pennsylvania.

The hold was a parliamentary procedure permitted by the standing rules of the U.S. Senate, a senatorial courtesy that couldn’t be challenged. It prevented the Senate from voting on the president’s two judicial nominations.

Fumo’s political slogan was “We Get Shit Done.” His formula for success: “Brains, Balls, Loyalty, and Leverage.” To accomplish his goals, Vince Fumo, the lifelong Democrat, would engage in political horse-trading with anybody, even a Republican like Santorum. (A spokesman for former U.S. Senator Santorum did not respond to requests for comment.) Thanks to the senatorial hold, Fumo, a state senator from Pennsylvania, currently held leverage over the President of the United States.

Fumo admitted to the President that he was the guy behind the senatorial hold placed by Santorum. The President asked about Legrome Davis, who, in Fumo’s opinion was not fit to be a judge.

Fumo told the President he had his own candidate he was backing for an appointment to the federal bench — Robert Scandone, a Philadelphia lawyer — but that Fumo’s nomination was also stalemated.

As Fumo recalled the conversation, the President said, We’re vetting your guy right now, so why don’t you release my guys?

Fumo knew this wasn’t true; nobody from the federal government had even sent Scandone a job application. But there was no sense in picking a fight with the President of the United States at a formal dinner in his honor.

“No offense, Mr. President,” Fumo said, “But I don’t trust anybody in the White House. When I get my guy, you get your guys. It’s as simple as that. And if you are indeed vetting my guy now, it won’t be long before we’re all happy.”

•

After dinner, a White House aide walked over to Fumo, and, in front of a half-dozen spectators, began ripping him anew over the two stalled judicial appointments. Clinton had played good cop; the White House aide was playing bad cop.

Fumo waited until the White House aide ran out of breath, and then he brought up his own judicial nominee, Scandone. The White House aide, however, was not there to negotiate. He told Fumo he wanted him to get out of the way of “our guys.”

“Not a chance,” Fumo said. “I’m not budging.”

“That’s the way it works, pal,” Fumo told the startled White House aide. “I get my guy, you get your guys.”

Why is Santorum doing this for you? the frustrated aide asked.

“Because,” Fumo said, “Let me tell you something. He [Santorum] is running next year. I’m gonna help him; you’re not.”

The White House aide stared blankly at Fumo.

“That’s the way it is,” Fumo repeated. “I get my guy, you get your guys.”

As Fumo walked away, he heard Rep. Borski crack, “Vince bounced him like a basketball.”

•

The presidential fund-raiser was held on a Friday night. The following Monday, the receptionist in Fumo’s Harrisburg office announced she had a call on hold from the White House.

Fumo picked up the phone. It was the same White House aide he had talked to at the presidential fund-raiser. Look, the aide said, I just faxed the paperwork and application for judicial appointment to your guy. So you can release our guys now, OK?

Fumo laughed. The President had told him at the fund-raiser that the White House staff was already vetting Fumo’s candidate. How could that be, Fumo asked the White House aide, if you’re telling me now that Scandone didn’t receive an official application until just a few minutes ago?

The President must have made a mistake, the White House aide said.

“OK,” Fumo said. “When my guy is nominated, all three of them will be confirmed together.”

The aide reminded Fumo that he had just personally faxed Scandone an application for a federal judgeship. So there was no need to continue the stalemate.

“Look, I’ve been around for a while,” Fumo said. “That’s the oldest trick in the book. Just before the election, the candidate gives committee people applications for patronage jobs. And after he’s elected, the applications get thrown into the trash.”

The aide changed the subject, asking Fumo what he thought about Legrome Davis, the Philadelphia judge whom Clinton had just nominated to the federal bench.

“He’s an asshole,” Fumo said.

He heard a click on the other end of the line.

•

Fumo never heard again from the White House aide. But that wasn’t the last he would hear about Davis.

A year later, in January 1999, President Clinton would renominate Davis to become a federal judge. And once again, Santorum, at Fumo’s request, would apply a senatorial hold, effectively killing the Davis nomination a second time.

Once again, the President intervened, requesting that Fumo drop his opposition to Davis. And once again, Fumo refused. But it was only a temporary victory.

Three years later, in 2002, another president, George W. Bush, a Republican, would nominate Davis to the federal bench for a third time. And this time around, Davis’s nomination would be successful, despite Fumo’s continued opposition.

The punch line: a year after he was finally sworn in as a U.S. District Court judge, the Honorable Legrome D. Davis was assigned to preside over a federal grand jury in Philadelphia that was investigating a prominent local politician for corruption.

The target of that investigation: Vincent J. Fumo.