August 03, 2019

Stephen Silver/Philly Voice

Stephen Silver/Philly Voice

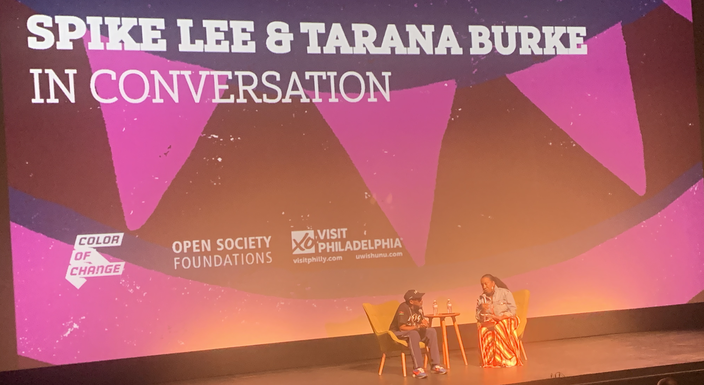

Spike Lee and Tarana Burke at the BlackStar Film Festival on Saturday, August 3.

The BlackStar Film Festival, an annual festival and conference showcasing the work of filmmakers and artists of color, was held for the eighth time over the weekend at International House of Philadelphia and other locations around West Philly.

According to festival's founder and executive director Maori Karmael Holmes, this year's BlackStar festival is the largest ever, with the Annenberg Center added as a venue for the first time. But it's been important to her, she said, to keep up BlackStar's vibe.

"That's something that happened on its own but we've sought to preserve it," Holmes said of the energy at the event, which has been compared to a family reunion by more than one person. "Even with the growth of the programming, we're still keeping it to four days, and we're trying to keep it [in] a footprint of a walking distance."

In addition to films, panels, and appearances by the likes of Questlove, one of the major events of the festival was an on-stage interview Saturday afternoon between two-time Academy Award-winning filmmaker Spike Lee and Tarana Burke, the activist and founder of the MeToo movement.

The discussion was officially about the 30th anniversary of Lee's celebrated 1989 film "Do The Right Thing," as well as his overall body of work, which also includes such films as "Malcolm X," "Jungle Fever," "The 25th Hour," "Inside Man," and last year's "Blackkklansman," which finally won Lee his first-ever competitive Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

At one point Lee praised the city of Philadelphia for supporting his work, going back to the beginning of his career in the mid-1980s, and he also told a humorous story about Frank Sinatra being upset with Lee for including him in the Italian-American Wall of Fame in Sal's Pizzeria in "Do The Right Thing," and therefore requiring a ten-page letter in order to grant Lee permission to use some of his music in a subsequent film. Lee also specifically named movie critics who, in their reviews of "Do The Right Thing," had predicted urban rioting and suggested that Lee would have blood on his hands if such a thing occurred (none did).

But the latter part of the discussion was taken up largely by a very contentious back-and-forth in which Lee and Burke argued about the portrayal of women in some of the director's movies.

"I want to talk about accountability," Burke, the MeToo founder, said. "When we talk about accountability in the work that I am doing, the conversation often gets derailed, or co-opted, or transfixed, on guilt and blame. And even though I've said many, many times that harm happens on a spectrum, but people don't really hear that. I think we don't talk enough about accountability from a place of love and common ground."

Burke went on to ask Lee about "how your work has changed with the national conversation."

"My work has not changed because of what you're talking about," the director said. "My work has changed because I got married." He went on to describe his wife Tonya, who he married in 1993, as his "harshest critic." He went to say that if he could do it over again, he would remove the rape scene from 1986's "She's Gotta Have It."

"You've received a lot of criticism over the years about the way you portray women," Burke said, but Lee interrupted to say that he's gotten a bad rap for that. He pointed to his movie "Crooklyn," as well as Angela Bassett's portrayal of Betty Shabazz in "Malcolm X," as examples of more positive, multifaceted female characters in his movies.

"If you look at the films, if you look at the body of work, I think if you weigh it, it doesn't add up," Lee said.

Burke went on to reference "Girl 6," as well as what she described as "the one with the lesbians" (2004's much-maligned "She Hate Me," which was about a struggling business executive who starts a business in which he impregnates lesbian women.)

"You named two films," Lee retorted. "Somebody go to [IMDB] and tell me how many films I've done. I've been doing films two decades, and you're gonna pull out two or three films, out of 30 years of work?"

He went on to mention the last two seasons of his recent Netflix adaptation of "She's Gotta Have It," as well as Laura Harrier's role in "Blackkklansman," as more recent examples of his work.

The two went on to argue about the nature of critique itself.

"If you look at a body of work," Burke said, "and even if you love the person- and I love your work- but as a person who loves your work, I don't then get to say, 'ooh, I love this work. I have questions about this, this and that?'"

"Let's talk about 32 years of work," Lee said. "If you look at it, overall. The rep I have that Spike Lee has negative images throughout his work about black women, is bullshit."

"You're addressing it from the standpoint of you're sensitive about it and you want to defend it, so we can't even get to the actual question," Burke said.

"I'm not describing your whole body of work, I'm not saying Spike Lee don't like black women, I'm not saying any of that," Burke said. "I was trying to get you to talk about the criticism that you've received about portrayals of black women in your films. That's it."

"I thought I did talk about it," Lee replied. "When I said that my films changed when I married Tonya Lewis Lee, I said look at my films before I got married, and look at my films afterward, there's a difference, and I think that's it.

"Your question, to me, is something that's been dogging my career as a filmmaker and I said, my answer, to what, this bias, this critique to me, is more than just that question to me."

After Lee said again that his films distinctly changed after he got married, he was asked, by both Burke and crowd, "what is the difference?," although he didn't give a more specific answer than "look at the films!"

The crowd, which was majority female, appeared to mostly side with Burke. But the two hugged it out before leaving the stage.

Tarana Burke asked Spike Lee about the portrayal of black women in his films. #bsff19 #spikelee pic.twitter.com/ILuXAK5pG5

— Amanda G (@MandaJoy4) August 3, 2019

"I think he didn't hear the question," Holmes, the executive director, said in an interview afterward about Lee and Burke's exchange. "And I think that it can be hard- he's been critiqued a lot for his portrayals of women in his films, and I think that if he had heard Tarana's question, which was, 'here's an opportunity to talk about how you think you've portrayed women or to kind of clear the record,' I think we missed the opportunity to have that kind of rich discussion… I just wish he heard her and was able to actually answer the question."

Aside from Lee's appearance, the festival featured "Jezebel," from director Numa Perrier, as its opening film, while also hosting a Saturday night screening of "The Apollo," a documentary from Roger Ross Williams about the legendary Harlem theater. Both were Philadelphia premieres.

Questlove was on hand Friday for the premiere of the upcoming TV series "Hip-Hop: The Songs That Shook America," while the closing program of the festival Sunday night was scheduled to include the Philadelphia premiere of Solange Knowles' short film "When I Get Home." In addition to those films, the festival offered an extensive program of short films, as well as panels.

The festival's future is in a bit of flux, with International House shutting down at the end of the year. Holmes said she's concentrating on this year's festival right now and isn't sure about the future.

Holmes, who is also a filmmaker herself, added that "I'm particularly interested in moving beyond traditional form. I think we have a lot of space there, to move outside of the three-act structure, to move outside of even synching, in the ways that we think about how sound and image meet up, the way that things are edited, I think there's a lot of room for exploration. If you think about Coltrane, and about the Blue Note years as peak of jazz exploration, we're not there yet with cinema."

"Black people have been making independent films since Edison," Holmes said of the festival itself, "that's not a new space for us."