July 21, 2017

Courtesy of Scott Kirschenbaum/for PhillyVoice

Courtesy of Scott Kirschenbaum/for PhillyVoice

“Of Woman Born” is a documentary focusing on the experience of birth told through the intimate portrayal of one woman.

Pornography.

It’s ubiquitous. Accessible with a simple swipe on a cell phone, porn has so thoroughly imprinted the mindset of the forthcoming generation that it’s not uncommon for middle school boys to ask girls for “butt stuff.” In fact, Teen Vogue recently published an article informing their preteen and teenage female readers on the ins and outs of anal.

And opinions about porn are as wide ranging as the forms of sexual expression depicted.

Some deem pornography as a new drug. With t-shirt slogans such as “Porn kills love,” anti-porn activists urge users to give up the habit of masturbating to images of strangers and seek meaningful connection with real human beings. On the other side of the proverbial fence, we find entrepreneurial pornographers regarding porn as a form of libertine freedom. Pornography heralds the end of sexual repression of all kinds – and the rich lining of professional and amateur pockets. In the middle are the majority of us, navigating what it means to live in a culture awash with the products of a multi-billion dollar enterprise, a culture of instant explicit sexual imagery.

Regardless of where a person may fall in the pro-porn vs. anti-porn continuum, there’s one human act – involving the exact intimate regions of the body that porn commodifies – that falls far outside of porn’s umbrella.

That act is birth.

We are all born of women. Whether through a vaginal delivery or through cesarean section, we literally emerge from another person’s body. And labor, especially if it is a natural labor, involves nudity, sounds, movements, moans, breath, blood, rhythmic rocking, and the ample amounts of the hormone oxytocin (released when we bond and care for each other). Birth is sensual and an intimate event, true. It can even be an orgasmic one. But it is not pornographic. I imagine this is one thing that both the pro-porn and anti-porn advocates can agree upon.

Birth is birth; it is not porn.

Given this, it came as a stark and difficult shock when Yale graduate and documentary filmmaker Scott Kirschenbaum began to promote his new, innovative and deeply moving film focusing on birth and ran into censorship trouble.

“These Are My Hours” is a documentary focusing on the experience of birth told through the intimate portrayal of one woman. Kirschenbaum writes: “[This is] the first documentary filmed entirely during a labor, and the first told from the perspective of someone giving birth.”

The film will be released early 2018 with a festival run and then hopefully national distribution via HBO, Netflix, Amazon or a comparable outlet. On April 19 of this year, Kirschenbaum posted an initial trailer. But Facebook banned his efforts to advertise and promote the trailer.

The process repeated. The production team at “These Are My Hours” posted images from the film. They shared trailers, posters, and ads. Again and again, posts were blocked and banned by Facebook restrictions that lumped together the documentary’s focus on birth with Facebook’s policy of blocking pornographic content. Emily Graham, the mother featured in the film, had her personal page frozen multiple times after posting images of the film. Even the banner photo used on the film’s Facebook page had to undergo significant cropping to be deemed permissible to share.

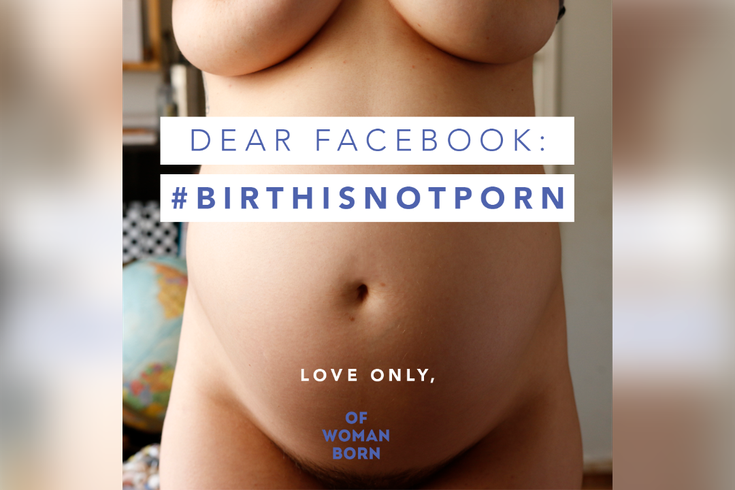

On May 27, an official campaign, launched on the “These Are My Hours” Facebook page began. The campaign, entitled “Birth is Not Porn,” has struck a powerful nerve with birth activists and mothers.

For example, June 5 was deemed a “Day of Action” and individuals were invited to post photos to the “These Are My Hours” Facebook page “that had been previously flagged, removed, not approved for advertising or otherwise restricted on Facebook in the past.” The campaign aimed to send a powerful message to Facebook condemning “birth imagery censorship.”

Photos and films depicting the wondrous, difficult, amazing, and heroic journey of a mother to open her body and bring forth life are to be honored and lifted up, not banned.

Currently, the notification system in Facebook groups together images of nudity with “sexually suggestive” content. Such a system is a byproduct of a culture so thoroughly inundated with sexually explicit images of the body, particularly the female body, that any act done by said body is deemed pornographic.

The Birth is Not Porn campaign sought fundamental changes to Facebook’s notification system and on June 12, Kirchenbaum made headway. He spoke with lawyers representing Facebook and the company agreed to overturn the prior censorship of the trailer and photos from the film.

But official policy remains unchanged and images depicting nipples or vulvas are still flagged as inappropriate. We have so conflated a woman’s body with a one-dimensional and taboo vision of sexuality that even images of the most primal act we all share, the act of being born, are considered pornographic.

The Birth is Not Porn campaign argues that it is misogynistic to claim “that women’s bodies doing quintessential women’s work (birthing babies) is too vulgar for ‘the public’ to see.” They continue: “Are we permitted to single out any other group’s bodies as ‘sexually suggestive’? The ingrained patriarchal view of the female form runs so deep that many don’t think to question it.”

But question it we must.

No one should receive a flagged objection from a social media site for posting a photo of her or his child’s birth. The human body, let alone the human self, is multifaceted. While sexuality is one significant part of our being, it is not the only part of who or what we are. Bodies are not to be viewed through a one-dimensional lens. Photos and films depicting the wondrous, difficult, amazing, and heroic journey of a mother to open her body and bring forth life are to be honored and lifted up, not banned. And certainly they are not to be regarded as anything even remotely analogous to sexually explicit content.

Birth is birth, not porn.

For more information on the film, visit thesearemyhours.com.

Interested in Amy Wright Glenn's work? Sign up for Amy's email newsletters today.