George Anastasia had covered the Philadelphia Mafia for more than a decade when he received a call from a hitman ordered to kill him several years earlier.

Former mob boss John Stanfa allegedly commanded Sergio Battaglia to murder Anastasia in the early 1990s by throwing hand grenades through the windows of his home.

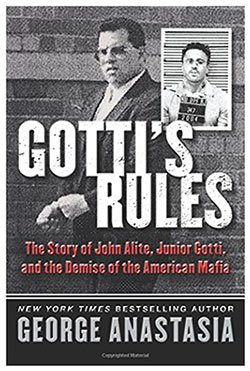

RELATED EVENT: 'Gotti's Rules' author to hold public reading at the Free Library

Anastasia learned of the plot — which was never attempted — in 1996, when Battaglia was serving as an informant for the FBI.

“He called me from prison and told me the story,” Anastasia said. “He said to me, ‘It was nothing personal.’ I said, ‘Sergio, I have a wife and two kids. If a hand grenade comes through the window, it’s very personal.’”

Anastasia insisted it is the only time he has feared for his security during a decades-long career covering organized crime. A writer for bigtrial.net and a former reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Anastasia has penned six books on the Mafia and served as a consultant for television productions about the mob.

Anastasia spoke with PhillyVoice last week, detailing the book, his career and the state of the Philadelphia Mafia. The book offered Anastasia an opportunity to tell the story of the mob through the lens of Alite, an enforcer for the Gambino crime family in New York.

“I was trying to deconstruct the myths of the mafia and deconstruct the myths of the Gotti family,” Anastasia said. “The whole idea that this is about honor and loyalty is pretty much nonsense. It’s pretty much about treachery and deceit.”

The actual Mafia, Anastasia said, is far from the romanticized version depicted in The Godfather and The Sopranos. If anything, it resembles the grittiness displayed in Goodfellas.

“It’s not about Don Corleone, man of honor, ‘let me take care of my family,’” Anastasia said. “It’s more about, ‘give me the money and if you don’t give me the money, I’m going to break your knee.’”

Or worse.

Alite pleaded guilty to two murders, four murder conspiracies and at least eight shootings in 2008. He also acknowledged his participation in multiple armed home invasions and robberies.

“I think the American public has always been fascinated by the outlaw, whether it was Jesse James, John Dillinger or Bonnie and Clyde. I think that’s just part of the American psyche. We like the outlaw. We like the rogue.” – George Anastasia

Alite, who pitched his story to Anastasia, agreed to testify against Charles Carneglia, another Gambino family enforcer convicted of four murders. He later testified against John A. Gotti, better known as "Junior Gotti" and the son of former Gambini boss John J. Gotti.

Cooperating with authorities has become much more common, Anastasia said. Aided by the Federal Witness Protection Program, mobsters opt to testify against their families. Secrecy and loyalty have withered.

“You never used to see that back in the '50s and '60s,” Anastasia said. “The guy would be dead if he did that.”

Federal prosecutions are just one factor that has left the mob decimated, Anastasia said. Others include sophisticated surveillance, competing underworld groups and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act.

Plus, Italians no longer face limited opportunities in the professional world. With the brightest Italians chasing careers that bring them riches legally, Anastasia said the mob must scrape from the bottom of the gene pool.

The scene is no different in Philadelphia, Anastasia said. Mobsters began testifying against one another in the late 1980s and early 1990s, breaking apart the Mafia’s influence. Now, no one is certain who is running Philadelphia’s mob.

The Daily News reported last week that a three-headed committee consisting of Steve Mazzone, John “Johnny Chang” Ciancaglini and Philip Narducci might be at the helm. Or it could be Joseph “Uncle Joe” Ligambi, the former boss who returned to South Philly last year after surviving 32 months in federal prison while being tried twice on racketeering charges.

“It’s valid to raise the question of who’s in charge,” Anastasia said. “I think the more important question is, given what’s happened to the Philly mob, why would anybody want to be boss?”

Two of the six mob bosses who preceded Ligambi were murdered. The other four ended up serving lengthy prison sentences.

Yet, there is a sense of glory that comes with the title. The latest generations of mob bosses have flaunted themselves in a way their predecessors absolutely avoided, choosing to relish the celebrity rather than hide in the shadows, Anastasia said.

“I think the American public has always been fascinated by the outlaw, whether it was Jesse James, John Dillinger or Bonnie and Clyde,” Anastasia said. “I think that’s just part of the American psyche. We like the outlaw. We like the rogue.”

Convicted Philadelphia mob boss John Stanfa, seen in a March 17, 1994 file photo, allegedly planned to kill mob reporter George Anastasia, but was distracted by an internecine power struggle. (Chris Gardner, File / AP)

That dynamic created a career for Anastasia, who first began covering organized crime by happenstance in the late 1970s, when he was assigned to cover Atlantic City’s burgeoning gambling scene.

“Are casinos going to bring the mob to Atlantic City?” Anastasia said, recalling an early assignment. “The answer was the mob was already in Atlantic City.”

Anastasia began developing the Mafia beat, first by building up his sources on the law enforcement side and combing through police documents and court testimonies.

“The more I did, the better understanding I got of it,” Anastasia said. “I was very fortunate. Back then The Inquirer had a lot of resources. You were able to develop the beat and spend a lot of time on it.”

Anastasia got his biggest break when his connections led him to Nick Caramandi, a wiseguy whose testimony landed former Philly mob boss Nicky Scarfo and his associates in prison. Caramandi provided the backbone for Anastasia’s first book, “Blood and Honor,” published in 1991.

“It became a beat and I covered it the same way somebody cover politics, somebody cover sports and somebody covers the school board,” Anastasia said. “If you were involved in this life, you could expect me to be around because that’s what I covered.”

Many of the mob bosses simply ignored Anastasia, figuring the slaying of a reporter would cause more harm than good, Anastasia said. Stanfa, apparently, did not share that philosophy.

Unlike many other mob bosses, Stanfa was not born in America. He was from Sicily, where Anastasia said the Mafia has been known to knock off judges and prosecutors.

Upset by Anastasia’s reporting, Stanfa allegedly put out a hit contract. But Stanfa had bigger problems. The mob was split between two factions and some members were backing Joseph “Skinny Joey” Merlino.

So the hit never happened.

“(Battaglia) said they were so caught up in the war with Merlino that they stopped looking for me,” Anastasia said. “That was his explanation.”