The all-time Sixers one-on-one tournament returns for the second of our final four matchup, pitting Julius Erving, the heart of a contender for almost a decade, and Allen Iverson, the one-man band who almost took down the Lakers during a magical 2001 Finals run.

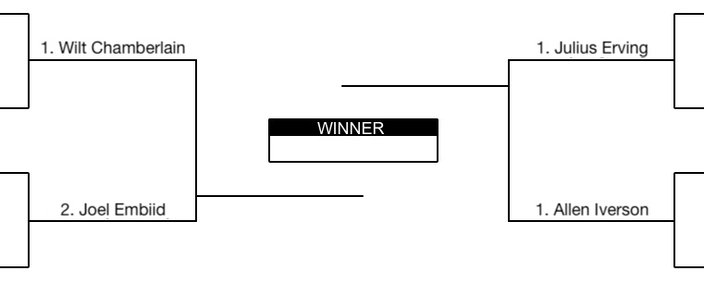

We took a bit of a break between the last final four matchup and this one, so just as a refresher, here's what the bracket looks like after extensive voting in each region. I must have done a good job picking the top seeds, because this thing has been mostly chalk:

(If you want to view the original bracket, you can check that out here. And you can see how each region played out by checking out our region final posts: Wilt | Barkley | Dr. J | Iverson)

A refresher for anyone new to this — these weren't the "best" 64 players, necessarily, but 64 players from an assortment of eras and categories that I initially was going to divide by playstyles (playmakers, scorers, finishers, and potpourri), before realizing you could put four or five of the greatest players in franchise history into the "scorer" category. I tried to account for some combination of impact, longevity, peak value, etc., with the first goal to split up the players I would consider to be the Sixers' version of Mt. Rushmore — Wilt Chamberlain, Julius Erving, Allen Iverson, and Charles Barkley. Critically, the players were not strictly seeded based on how good they would be in a one-on-one setting.

Here is a refresher on the rules:

- Players are being judged strictly for who they were/what their game was when they were a member of the 76ers. So in the case of someone like Chris Webber, you get the guy with bad knees, not the athletic force. In the case of Markelle Fultz, you get the player whose jump shot went missing, rather than the resurgent version with the Orlando Magic.

- Games are to 11, scored by ones and twos, and you must win by two.

- Make-it, take-it is in effect.

- There are no rebounds on missed shots, which count as a turnover. All changes of possession require players to check the ball at the top of the arc.

- Players can take a maximum of four dribbles per possession, to avoid gratuitous post-ups or smaller guards dribbling circles around bigs.

- Calling fouls is the responsibility of the defense. You are encouraged to factor in player personality and willingness to bend the rules when considering the impact of this rule.

- MORE ON THE SIXERS

- Are the Sixers screwed if NBA salary cap drops dramatically?

- The 10 weirdest and wackiest stats and records in Sixers history

- Charles Barkley says Sixers' Joel Embiid 'hates me' because of laziness criticism

- Elton Brand on his stars' health, keeping the team together and more

I must stress Rules No. 3, 4, and 5 above all others. This is not a game where big dudes can just pound people through the rim and live on the offensive glass, or a tournament where little guys can dribble circles around immobile bigs. Skill in isolation matters. You can vote however you want, but good basketball players tend to play a different style of one-on-one than the average person.

Here's how the results shook out in the Erving and Iverson regions:

1. ALLEN IVERSON (54%) over 2. Moses Malone

1. JULIUS ERVING (82.5%) over 2. Andrew Toney

The only thing surprising about these results was the margin of victory for the Doctor over Toney, as the latter is a cult hero and one of the deadliest scorers of his era. Erving was of course the better player, but I figured his running mate would get more love. No surprise that the youth vote powered The Answer to a victory.

So that brings us to a classic matchup of two very different players from very different eras.

RELATED: Joel Embiid vs. Wilt Chamberlain face off in Final Four

1. Allen Iverson vs. 1. Julius Erving

Tale of the tape

Iverson: 26.7 points/3.7 rebounds/6.2 assists on 42.5/31.3/78.0 shooting splits. 1x NBA MVP, 11x All-Star, 7x All-NBA, Rookie of the Year in 14 seasons. Member of the Pro Basketball Hall of Fame.

Erving: 22.0 points/6.7 rebounds/3.9 assists on 50.7/26.1/77.7 shooting splits. 1x NBA MVP, 11x All-Star, 7x All-NBA, 1x NBA champion 11 NBA seasons. Member of the Pro Basketball Hall of Fame.

A brief note before we get rolling — Erving's stats and accolades above do not include his stint in the ABA, where he was widely considered the league's best player during his first five seasons of professional basketball. Erving was a 3x MVP and a 2x champion in the ABA, with better raw numbers (and similar efficiency numbers) across the board. That production is not being counted in this argument but is a part of his legacy that should be remembered and valued in the history books.

The case for Allen Iverson

The diminutive guard did not make it to the Final Four by accident. For many younger fans, Iverson has the single most memorable season of their lifetime, and the team's 2001 Finals run was a testament to exactly how dangerous The Answer was at his peak.

Everyone remembers Game 1 of the 2001 Finals, when Iverson poured in 48 points and hit Tyronn Lue with a stepover that has outlasted any moment (and even in some respects the outcome) from that series. But that game was just one of many in an absolute assault of NBA teams from mid-April through mid-June that season. He scored 45 points in Game 2 vs. Indiana, 52 in Game 5 and 54 in Game 2 vs. Toronto after Philly dropped the first game at home, and added back-to-back 40+ point games to close out a seven-game slugfest with the Milwaukee Bucks, a feat he managed after having to sit out Game 3 with hip pain.

That Game 7 performance against the Bucks, by the way, should come up far more often than it seems to. 44-6-7 in a game he controlled from start to finish, punishing Milwaukee from the start and sustaining that momentum all the way through the biggest win for the franchise in almost two decades. This one was an absolute classic, and Iverson had it all going — three-point shooting, blow-bys, touch shots at the rim, the works.

Iverson, to state the obvious, was a warrior. His shot selection wasn't always good, he would go on cold stretches that made you want to tear your hair out, and yet there he'd be in the fourth quarter, coming alive for five, 10, 15 straight points and suddenly the Sixers had a chance to win. His volatility was easier to live with because of his lack of fear and the ability to deliver as the stakes grew.

All of the traits that made him dangerous in a five-on-five game make him even tougher to deal with in a one-on-one setting. There's no help coming if he gets you with the electric first step. Finishing over and through length was something he did well, and his willingness to initiate contact would help to disarm Erving as he loads up to jump and contest shots at the rim. In the event that the game turns into a jump-shooting contest, Iverson would have the better chance to get hot and shoot Erving out of the game.

One thing that stands out with Erving looking back on old games — he was much better as an off-ball defender/gambler than he was a stopper. When he was matched up with quicker players, Erving's fundamentals often let him down, clearing paths to the lane for guys who could simply get the first step on him. With Iverson in possession of one of the game's all-time great first steps, there's a non-zero chance Erving would find himself chasing Iverson's dust.

Philadelphia never found a second option to take the burden off of him on offense, and that allowed teams to gear up to stop the one-man show. It hardened habits that proved tough to break and helped put a ceiling on him as a player, which admittedly was still extraordinarily high. None of that matters here. The gifted scorer and tough-as-nails competitor has a chance against anybody, and certainly here.

The case for Julius Erving

If not for the presence of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, whose case as the greatest of all-time is under-discussed compared to those of Michael Jordan or LeBron James, Julius Erving would have gone down as the best basketball player of the 1970s. Though he didn't join the Sixers until over halfway through that decade, his impact was felt immediately, with the 1976-77 Sixers making a run to the NBA Finals in the first post-merger season.

Iverson is given credit for dragging a relatively weak supporting cast to the 2001 Finals, but Erving doesn't get the credit he probably deserves for consistently giving the Sixers a platform to build from. The Sixers won at least 45 games every year he was in Philadelphia, including a 1979 season in which they lost Doug Collins to an injury that altered his career trajectory. He had plenty of help, and Moses Malone was the man who put them over the top, but it was Erving who allowed the Sixers to be serious contenders for most of a decade from the mid-70s through the mid-80s.

Dr. J was capable of adding a little bit of everything to a game as the moment dictated it, using outlier athleticism and prototypical size to overcompensate for a jumper that came and went. Starting possessions from the perimeter drags Erving away from his favored spots in the mid and low post, but his size and strength would make it easy for him to shield the ball from Iverson and get to whatever spots he wanted on the floor. He had touch that was mostly reliable from the free-throw line and in, and just going over the top of Iverson would be an option on most possessions.

Many of Erving's issues in a typical halfcourt setting aren't relevant here. In deep playoff runs with the Sixers, better teams would try to pack the paint and play pseudo zone to stop his trips to the rim. There's no extra help coming for Iverson here, and without it, Erving's ability to hang in the air, finish through contact, and punish smaller defenders would be hard to stop here. Iverson had defensive issues even on his best day, and he has no recourse other than gambling for steals against a guy who can outmuscle and outleap him.

His fundamental issues notwithstanding, Erving has physical traits that would allow him to make up for any mistakes made on the defensive end against Iverson. Iverson could be a slow operator in the halfcourt, a player who preferred trying to lull guys to sleep with his handle, and with the dribble-limit in this game, his options against Erving would be limited. The older legend would make certain moves, a la the stepback jumper, tougher for the smaller Iverson to bang home.

Erving's early years in Philadelphia were marred by high-profile defeats for the team in big moments, but those were not necessarily on his shoulders. Their loss to Portland in the 1977 Finals after being up 2-0? Erving scored 37 and 40 points in the final two games of that losing effort. Magic Johnson's all-time performance in the 1980 Finals with Abdul-Jabbar on the shelf? Erving managed 27-7-3 in defeat. He had his limitations and was not Magic or Kareem, to be sure, but the moment was not too big for him. I imagine he would handle himself okay in a made-up one-on-one tournament.

Both of these players have stylistic issues that would have to be worked through to win this matchup, and I don't think it's a no-brainer for either guy. If I was forced to decide, I think I would go with Erving, as I think his physicality would be too much for the smaller man to handle. But if anybody has earned the benefit of the doubt in a David vs. Goliath battle, it's Iverson.

Cast your votes and sound off below. We'll have the final matchup next week.

Follow Kyle on Twitter: @KyleNeubeck

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice Sports

Subscribe to Kyle's Sixers podcast "The New Slant" on Apple, Google, and Spotify