September 19, 2022

Scott Warman/Unsplash.com

Scott Warman/Unsplash.com

Drinking alcohol is a big part of American culture, but most Americans are unaware that consumption increases their likelihood of several forms of cancer. Updated warning labels could better educate the public, a pair of doctors write in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The health risks associated with alcohol consumption are well-documented, but some scientists say that warning labels affixed to alcoholic beverages are not worded strongly enough to properly educate consumers about their increased cancer risks.

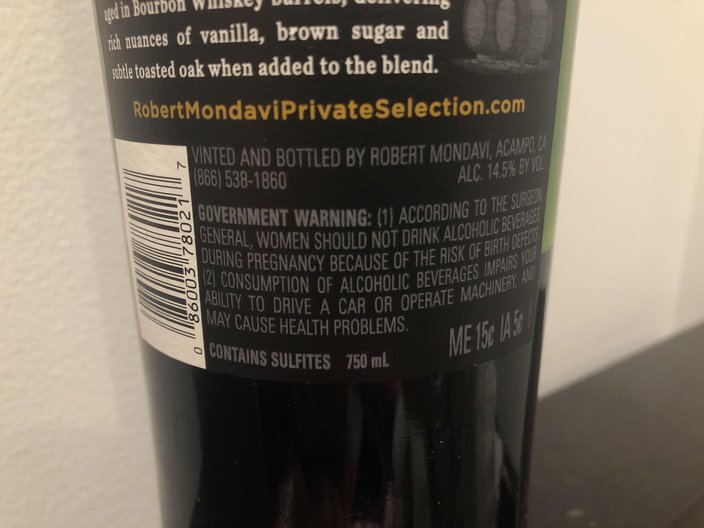

The labels, which have not been updated since the late 1980s, are vague about the potential health risks of alcohol, particularly the increased likelihood of cancer, a pair of doctors argued in an article published by the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this month.

Dr. Anna H. Grummon, of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and Dr. Marissa G. Hall, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, noted that alcohol consumption accounts for 140,000 deaths each year in the United States. Yet, data suggests about 70% of Americans are not aware that drinking alcohol increases their risk of several forms of cancer, including those of the breast, head, neck, esophagus, liver and colon.

They wrote:Although the alcohol industry has worked to spread the idea that alcohol consumption has health benefits, research suggests that its risks outweigh potential benefits, on average. In addition to the data on fatal and nonfatal injuries resulting from acute intoxication (including injuries caused by motor vehicle crashes), mounting research links longer-term alcohol consumption to chronic diseases including hypertensive heart disease, cirrhosis, and several types of cancer. Even light or moderate drinking increases the risk of these conditions, particularly cancer. Yet according to the CDC, two thirds of U.S. adults report drinking alcohol.

The federal government's Dietary Guidelines for Americans suggest men should have no more than two drinks a day and women should have one or less a day, but even moderate alcohol consumption comes with some risk.

Long-term, excessive drinking can cause, or worsen the progression of liver disease, cancer and heart disease, as well as mental health problems, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overconsumption also contributes to the number of car crashes and suicides in the country each year.

The CDC estimates that about 1 in 10 deaths among adults ages 20 to 64 are due to heavy drinking. Long-term, heavy drinking shortens a person's life by an average of 26 years, data shows. Even people who have no more than one drink per day have a modestly increased risk of some cancers, according to The National Cancer Institute.

These are all good reasons to update the warning labels on beer, wine and liquor, Grummon and Hall wrote. Since 1988, all alcohol products must carry a health warning statement, but they the current label mainly warns against drinking while pregnant or operating vehicles. It doesn't clearly warn against cancer risk, the doctors said.

The warning label affixed to alcoholic beverages in the United States has not changed since 1988. Some scientists say it needs to be updated to more precisely state the cancer risks associated with drinking alcohol.

The current label "lacks all the key elements of evidence-based warning design," including larger text, more pictures and a more prominent placement, Grummon and Hall wrote. They emphasized that Americans should be given all the information necessary to make a well-informed decision about their alcohol use.

They wrote:

Consumers have a right to know about any serious health harms associated with products they might buy. They can then do their own calculations to determine the amount of risk they are willing to tolerate, just as all people do as part of the many decisions we make every day. In the absence of government intervention, however, the alcohol industry has little incentive to communicate these risks.

So can a drinking habit actually cause cancer? Yes, according to a large genetic study published earlier this year. The researchers found a clear causal relationship, reinforcing the need to lower alcohol consumption in countries with increasing drinking rates.

According to Lancet Public Health data, alcohol may cause about 3 million deaths worldwide, including over 400,000 from cancer, every year.

In the U.S., drinking alcohol is big part of the culture, but in the last decade, alcohol misuse has become a major health issue, which the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated.

From March to September 2020, the U.S. saw a 20% increase in liquor store sales compared to the same time time period in 2019. Additionally, alcohol consumption rose by 14% among adults over age 30 during the early months of the pandemic, with women seeing the biggest increases. And last fall, a poll found that nearly 1 in 5 Americans reported drinking heavily within the previous 30 days.

The increase in alcohol misuse has doctors worried about its affect on cancer rates. But how does alcohol actually increase a person's risk for cancer? Scientists say there are several mechanisms by which alcohol can cause cancer:

• The ethanol in alcoholic drinks breaks down to acetaldehyde, a toxic chemical and probable carcinogen.

• Alcohol impairs the body's absorption of important nutrients, such as vitamin A, folate, vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin e and carotenoids.

• Alcohol increases blood levels of estrogen, which is linked to the risk of breast cancer.

Some alcoholic drinks also may contain other carcinogenic chemicals that are introduced during the fermentation process, including nitrosamines, asbestos fibers, phenols and hydrocarbons.

Moderate drinkers are 1.8 times more likely to develop oral cavity cancers, excluding the lips, and throat cancers, according to the National Cancer Institute. They also have 1.4 times the risk of developing larynx or voice box cancers. These risks are even higher among heavy drinkers.

Alcohol consumption at any level has been linked to an increased risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, a type of esophageal cancer. It is 1.3 times higher for light drinkers and almost 5 times higher for heavy drinkers. Researchers also have found that heavy alcohol consumption doubles a person's risk of two types of liver cancer — hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

The risk of colorectal cancer is 1.5 times higher among moderate to heavy drinkers compared to people who do not drink. The risk of breast cancer gradually increases with the level of alcohol intakes, with heavy drinkers having the highest risk.

Research is not clear how alcohol affects the risk for other cancers, including those of the ovary, prostate, stomach, uterus or bladder. But recent evidence suggests it might impact the risk of prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer and melanoma.

Additionally, studies have shown that reducing alcohol consumption – or quitting – can lower the risk of cancer.

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice