April 14, 2015

Handout Art/for PhillyVoice

Handout Art/for PhillyVoice

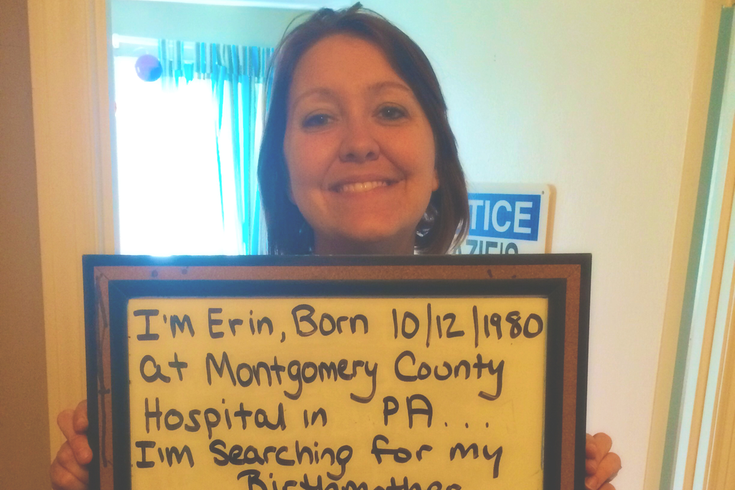

Erin Campbell, 34, is using Facebook as a search tool for finding her birth mother, with the ultimate goal of obtaining her family medical records.

When Erin Campbell, of Delaware County, gave birth to her first child six years ago, the newfound responsibilities of motherhood shed light on a problem she'd never given much thought: As an adoptee, she knew nothing about her birth family's medical history.

The most recent effort to modernize adoption law in Pennsylvania, Act 101, was signed into law by Gov. Tom Corbett in 2010 and set out to streamline the longwinded search for birth parents and adoptees through a registry. The registry, the Pennsylvania Adoption Information Registry (PAIR), requires agencies to submit medical information for future access from today's adoptees. However, for older adoptees, the registry has proven less effective: As a volunteer-only system, it depends on both the birth parents and the adoptee to submit paperwork to the registry, as well as pay fees that can range from $25 to $600 by the time the intermediary process ends -- with no guarantee of a match.

According to data from the Department of Human Services, dated March 9, PAIR has had 338 adoptees register, along with 312 birth parents. Intermediaries, which consist of agencies paid to do Campbell's type of do-it-yourself detective work, have facilitated a mere 15 matches since the registry's inception in April 2011.

"I’ve had a lot of mental anguish over this through the years – it screws with your head," he says. "It’s a major identity crisis. When you have no idea where you came from and you’re taught all your life to just be grateful that somebody adopted you, that’s a real mind-f---."

Family therapist and adoption specialist Abby Ruder, based in Wyndmoor, Montgomery County, told PhillyVoice that denying access to an original birth certificate belittles the experience of an adoptee - the implicit message from the commonwealth being that they're perpetual children who can't handle the information. It insists that there's a secret worth sealing.

The consequence, then, is the "anguish" adoptees like Faden report.

"I’ve had a lot of mental anguish over this through the years – it screws with your head. ... It’s a major identity crisis. When you have no idea where you came from and you’re taught all your life to just be grateful that somebody adopted you, that’s a real mind-f---," Izzy Faden, adoptee from Northeast Philadelphia.

"There used to be this old adage that 'What you don't know won't hurt you,' and what we've learned over the years, is that's simply not true," Ruder says. "It’s a fundamental human right that we all have the ability to know how we got into the world, how we got here, and it’s a very integral part of our identity development. There’s no reason to have these kinds of secrets and mysteries."

Our concern about HB 162 is the unilateral release of identifying information without the consent of all parties involved in an adoption. ... Many, many more abortions occur in Pennsylvania than infant adoptions, but Pennsylvania does not ask women why they make that choice. Our agencies have worked with rape victims and sex trafficking victims who want to give a good life to their babies, but want to heal and move on from the crimes committed against them. I’ve heard about at least two instances where rape victims chose adoption over abortion because of the confidentiality. The intermediary system gave them peace of mind. Parents wishing for privacy in an adoption are unwilling to come forward to testify against a proposal like HB 162, so their stories are often untold.

To be clear, there is no documentation of the abortion-to-adoption ratio because adoption agencies, in general, aren't actually required to report successfully placed adoptions to the commonwealth, making the math a guesstimate at best. Moreover, it's difficult to track an adoptee at all after their birth certificate is altered.

The conference representative also clarifies that, despite PACC's focus on preserving confidentiality for birth parents, it does not necessarily discourage those seeking their birth parents from doing so, but does value the use of "skilled counselors" who serve as intermediaries and allow for a more "positive experience" and "happy" connections.

Pennsylvania's Catholic Charities Counseling & Adoption Services charges a fee for adoptees who seek identifying information about their birth parents. PACC told PhillyVoice those services "usually" operate at a loss, but advocates argue that the conference would lose money from the passage of House Bill 162.

"As a birth mother, you want to make sure that after all those years your son or daughter is OK -- you never knew if they were sick or safe," Hoard explains.

She gave birth to her son in 1964 in Florida, which has birth certificate access restrictions similar to those in Pennsylvania. In the '90s, after attending an adoption conference in Philadelphia, she decided to try and find her son through Catholic charities that had worked on her adoption case decades earlier; the charities notified her that her son had tried reaching out to her, but by the time she realized as much, her son had died of meningitis.

"His wife got in touch with me and told me she thought our contact was something he needed, that he was troubled in some ways about being adopted, but he passed away before anything happened," she says. "I don't want to see adoptees have to go through what he had to go through."

Amanda Woolston, a licensed Kennett Square-based social worker, founder of Pennsylvania Adoptee Rights and adoptee, is the horror story Campbell likely imagines when worrying about not having medical history for her kids.

Woolston was diagnosed with a benign tumor under her neck at age 21 and, scared to death, sought out her birth family for medical records; upon finding them, she was immediately enlightened that her situation -- though frightening -- was not all that unusual.

"The first question they asked me when I found them was, 'So, when was your first tumor?'" Woolston says.

Woolston was fortunate to have been born in Tennessee, one of 13 states that offers open access to birth records. But had she been born in Pennsylvania, she emphasizes, she would have been pulling a Campbell -- circulating a Facebook photo in an uphill climb to find her birth parents.

That she can access her records and Campbell can't, then, is an issue of inequality and an indication, she says, of larger failures in the adoption system that get overlooked. Some agencies, she says, might not want legislation like House Bill 162 passed out of fear that less-than-ethical past practices might be found-out.

“So many adoption issues get swept under the rug because they’re not pleasant to listen to. … No one wants to believe we have work left to do with children and adults' rights post-adoption, and it’s uncomfortable to think that this institution that has a great, shining reputation in society actually has work left to do," Woolston says. "But children, adults and families depend on us to be uncomfortable and listen to those stories."

Benninghoff, the sponsor of House Bill 162, has made an effort to explain the legislation as simply as possible to his legislative colleagues.

"Fundamentally, it’s about getting all Pa.-born citizens the same right. It’s as simple as that," Benninghoff told PhillyVoice. "I’m bewildered that, in 2015, we would want to jeopardize someone’s health -- future generations' health -- when we can be very non-descriptive and discreet in providing medical information."

"No one wants to believe we have work left to do with children and adults' rights post-adoption, and it’s uncomfortable to think that this institution that has a great, shining reputation in society actually has work left to do," Amanda Woolston.

Certainly, efforts will still need to be made after any legislation is passed to organize reunions and, more importantly, educate birth parents and adoptees alike that the law is even in place. Advocates like Woolston and Benninghoff are careful to say that access to a birth certificate isn't a one-way ticket to your birth parents or your medical records.

As for the Catholic Conference's latest argument against the bill, Benninghoff cites it as one of many made in recent years to delay legislation.

“Obviously, we are empathetic to anyone in those [sexually violent] situations -- those of us who are put up for adoption do not always know what situation we were conceived under, and we are all also cognizant that someone made the choice for us to have life, and we're very respectful of that," Benninghoff says. "But part of me questions in my mind, after the amount of years we’ve been working on this, that we haven’t heard from one person in that incident. With the ability to communicate -- I get a lot of anonymous letters in my office from a whole array of issues -- I can’t imagine with today’s technology that we have not heard that, and the only group of individuals who’ve raised that is the Catholic Conference."

Benninghoff is optimistic that the bill will pass through the House and says he plans to loop in Gov. Tom Wolf sooner rather than later.

Because, he says, "It would be nice for Pennsylvania to not be the last state to act on this."