December 19, 2017

Photo courtesy/Penn Museum

Photo courtesy/Penn Museum

The skull found in the final resting place of H.H. Holmes in a Delaware County cemetery. Holmes was convicted and executed by hanging in Philadelphia for the fiery murder of an accomplice and friend.

First of two parts

In excavating the remains of a serial killer, certain considerations come into play.

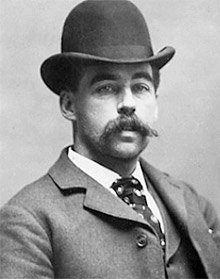

In the case of this past spring's exhumation of the notorious 19th century con man and serial killer Herman Webster Mudgett, better known as H.H. Holmes, two scientists at the University of Pennsylvania's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Samantha Cox and Janet Monge, had one chief concern.

That no died in the process.

For all they knew about Mudgett, who was convicted of killing one man but suspected of murdering many more as America's first serial killer on record, the scientists wanted to make sure he didn't have a final deadly trick up his sleeve more than a century after his execution.

An insurance swindler as well as murderer, Mudgett was finally captured by private detectives in Boston after dogged police investigations followed his murderous trail from Chicago, where he famously constructed a hotel with hidden rooms and passages to supposedly kill visitors to the 1893 World's Fair, through Philadelphia, where he fatally torched an accomplice in an insurance fraud scheme. By now Muggett, who fancied himself as deviously brilliant as his literary hero, Sherlock Holmes, had adopted his better known alias.

While in prison, it didn't take long for the serial liar as well as a serial killer to encrust his story with legend and lore. As if the nine murders he is credibly suspected of committing weren't horrific enough, he claimed to have killed 18 others, but many were later discovered alive. At one point, his alleged death toll reached 200 murders, with little evidence to support the claim. He was hung at Moyamensing Prison in South Philadelphia on May 7, 1896 at the age of 34.

Since then, interest in Mudgett, who fancied himself as deviously brilliant as his literary hero and inspiration for his alias Sherlock Holmes, has risen and fallen since his capture.

Like a dark fairy tale, each generation seemed to remake Holmes to fit their needs.

In the 1940s, he was the object of cheap pulp thrillers.

In 1974, he was the villain in a novel by the author of "Psycho."

In 2003, he was the dark heart at the center of the best-seller, "The Devil in the White City," which is slated to get the Hollywood treatment with Leonardo DiCaprio as Holmes. He was even the topic of TED talk.

Herman Webster Mudgett took his alias because he fancied himself as deviously brilliant as his literary hero, Sherlock Holmes.

Now, this past summer, the legend of H.H. Holmes continued in a History Channel documentary, "American Ripper," which explored years of rumors and the suspicion held by author Jeff Mudgett that his great-great-grandfather escaped his Philadelphia execution, fled to England and continued his murderous spree, this time as Jack the Ripper.

To find out, Jeff Mudgett and the History Channel enlisted the help of Monge and Cox, both Penn archaeologists, to oversee the disinterment of H.H. Holmes's remains and, through modern-day forensic science, determine if he was indeed in the grave marked for him.

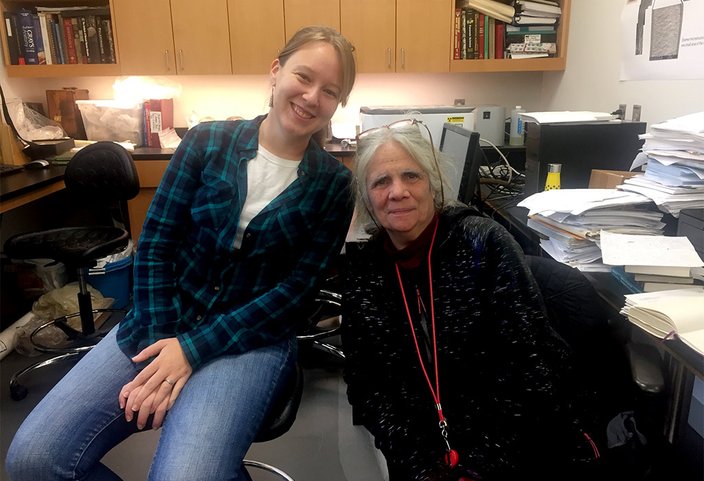

The task turned out to be even more dramatic than anticipated for Monge and Cox, associate curator in charge of the museum's physical anthropology section and consulting scholar at the museum, respectively.

Already contending with a tight deadline to excavate the body and the discovery of a false coffin, they had learned of a potentially life-threatening concern: that opening the grave would expose the crew to what the World Health Organization calls the most deadly infectious disease in the world.

Dr. Samantha Cox, left, and Dr. Janet Monge, scientists at Penn's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, helped exhume the body of H.H. Holmes, a notorious 19th century con man and serial killer. “You hear ... all this crazy stuff about how Holmes had escaped and we're like 'yeah, yeah, we're going to get in there and get the body ... and then we get down there to this empty box, Cox says. ”We were tearing our hair out.“

It's an unavoidable cliche to say if a movie were ever made of the scientific effort to get to the bottom of Holmes's final mysteries, the roles of Drs. Cox and Monge would be easy to cast.

Cox, young and earnest, is obsessed with history and eager to discover it in the field as well as in the library.

Monge, her mentor, while surrounded by the dead in her bone-filled office, is blessed with an infectious laugh, a wry sense of the absurd and a well-earned reputation with law enforcement. In her mid-60s, she has lent her archeological expertise at numerous crime scenes, including the House of Horrors of Philadelphia serial killer Gary Heidnik, where she helped in 1987 to identify the charred remains of his victims as a graduate assistant. More recently, she was among the researchers who determined that the Irish immigrants secretly buried in a mass grave in Duffy's Cut near Malvern, Chester County, were the victims of homicide and not cholera.

Even before a single shovelful of dirt could be tossed aside, Cox had to determine one thing: could the deadly bacteria still be alive and virulent in his grave?

And as scientists, they said, their first task was to read everything they could about Holmes, whose trial attracted national press attention.

"There was a lot of coverage, which was great for us," Cox said. "But everyone had different stories about different things. (Holmes) was creating his own legend."

Thanks to extensive interest in Holmes, even in the medical community which at the time searched for physiological reasons for the remorseless killer's appetite for mayhem, his health records were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. There, Cox learned that Holmes had tuberculosis, a highly infectious airborne bacteria that attacks the kidney, spine and brain. It killed 1.5 million people in the world in 2016 and 470 in the United States in 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Concerned that grave robbers would target his remains after his execution, Holmes requested that he was buried 10 feet into the ground and his coffin encased in concrete. So even before the first shovelful of dirt could be tossed aside, Cox had to determine one thing: could the deadly bacteria still be alive and virulent in his grave?

The answer, after consulting with forensic journals and speaking with experts, including medical examiner's offices in Philadelphia and Delaware County, wasn't very reassuring.

It was a "maybe," Cox recalled.

"Don't you love it," said Monge, with a hardy laugh. "It was a good maybe.

In the end, it was a theme throughout the investigation into who was buried in the grave: the limits of science to provide definitive answers.

Excavating the burial plot of H.H. Holmes first revealed an empty wooden coffin, at right, then another wooden coffin underneath, at left.

Given the concern over tuberculosis and the possible state of the concrete encasing Holmes' coffin – if it remained intact "everything is trapped in there, it could be very nasty" – Cox decided everyone on the scene would have to wear filtration masks and gloves, and the number of people allowed to handle the remains would be relatively small.

Digging up Holmes would create other challenges. Unlike exhuming modern burials, which typically involves a concrete casing to protect the coffin and is relatively easy to perform – "you just lift out the lid and lift out the coffin," Cox said – most 19th century coffins went straight to the earth. And given Pennsylvania soils' acidic quality, it wasn't at all certain they would find Holmes intact if his requests to be buried in concrete hadn't been honored. So it was vital that the painstaking standards of an archeological dig be followed in bringing Holmes to light.

"I would have to say we were worried. Lots of famous folks are moved from where they're supposed to be buried, so it's not uncommon for this to have happened." – Dr. Janet Monge, Penn archaeologist

They also had a hard deadline imposed by Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, where Holmes is buried. Get the remains out by Mother's Day, the scientists were told.

"They didn't want us in there disturbing things when people were coming over to visit their loved ones," Cox said.

"It's cemetery hot times," Monge joked.

The two scientists, along with the History Channel's production team, gathered a team of experts in construction, concrete-cutting, excavation and medicine, including a geophysicist from Franklin and Marshall College, Dr. Tim Bechtel; the museum's Dr. Peter Cobb, who performed 3D photogrammetric mapping of the gravesite; and Dr. Martin Levin of the university's dental school, who helped identify the remains. About 30 people ultimately were involved.

At first, Monge and Cox, who was responsible for the field work, thought it would take five days to dig out H.H. Holmes.

It ended up taking much longer, as they tried to unravel one riddle after another.

Dr. Samantha Cox, left, and members of the team carefully scrub remains found in the grave of H.H. Holmes.

Holmes's burial plot is located well past the green, wrought iron gates of Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, in an unmarked grave lost among rows of marked graves in a well-trimmed plot of land, not far from a soaring tree in full bloom.

Uncertain what they would find, the archeologists came armed with heavy equipment. Rumbling down the lane were backhoes, flatbed trucks, even equipment used to hoist heavy statues in case they had to remove a giant block of concrete from the ground.

The first mystery as they started to scoop the earth on May 6: an intact beer bottle from a now-closed brewery. The bottle was shattered during the dig and the beer sadly lost to the damp ground. The researchers suspect the bottle ended up over Holmes's grave site because of ground shifting from an adjacent burial from the 1940s.

A second discovery, even more disconcerting, derailed the project for days.

An empty coffin.

"It was a little bit shocking," Cox said.

The team used a backhoe to remove the earth over the Holmes grave, until six feet into the ground "we could see some wood in the bottom of the trench," Cox said. "Then we went down there with hand tools and did the rest by hand."

This presented the first real variance with the reports surrounding Holmes's burial. According to sparse records kept by the cemetery, he had been buried 10 – not 6 – feet into the ground and, according to a handwritten note in the margins, in concrete.

This coffin, 8 feet long, 2 feet wide and 2 feet deep, was in concrete, but the mixture had never properly set. Instead, it became a heavy, gray clay mixed with the soil, but the coffin itself was intact.

In fact, the wood "was pristine; you could still see the yellow in the pine," Cox said.

It took three days to excavate the coffin, and they needed a saw to open it.

To their astonishment, it was empty. The five days they had budgeted to find Holmes was already up and still they had no remains.

"It was incredibly frustrating," Cox said. "You hear all these stories, all this crazy stuff about how Holmes had escaped and we're like 'yeah, yeah, we're going to get in there and get the body and it'll be fine and then we get down there to this empty box. We were tearing our hair out."

I would have to say we were worried," Monge said. "Lots of famous folks are moved from where they're supposed to be buried, so it's not uncommon for this to have happened."

On that fifth day, everyone involved in the project, from the president of the television production company to a representative of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which also had to give their approval for the dig, were at the gravesite, huddling to discuss whether they should press on.

In the end, "for the sake of completeness," Cox explained, they decided to continue the dig. "We wanted to know what was under the box."

The skull found in the burial place of H.H. Holmes in Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon. Finding it was only half the archaeologists' mission.

So they drilled holes at the bottom of the fake coffin – which by now they suspected was a decoy – to use a sounding probe to see if there might be another coffin buried underneath.

Tim Bechtel, the geophysicist, climbed down into the trench and, as groundwater started to seep in, inserted the probe through one of the holes. Within four inches "we hit something solid."

That was all the encouragement the crew needed to dig out the first coffin and find a second concrete container. Again, using hand tools and their own fingers, and surrounded by dozens of sponges to mop up the groundwater invading the trench, the team carefully chiseled away, as the smell of decomposition mixed with concrete perfumed the air.

Cox was standing in the narrow trench waiting to be interviewed by the television production team when she happened to look down and make a discovery that eased any doubts. There, on a vertical wooden board over the concrete container, illuminated by a slant of sunlight, were the names Mudgett and H.H. Holmes. Written in black wax pencil.

"As soon as it was exposed to air, [Holmes's mustache] started to flake off." – Dr. Samantha Cox, Penn archaeologist

"It was the first time we knew absolutely for certain that we found what we were looking for," Cox said. That wooden board was quickly taken to conservationists at the university, who used ultraviolet and infrared lighting to enhance and confirm the writing while the dig continued.

Now, breaking into the coffin required all the precision of an intricate safecracking, as preserving the body inside was of utmost importance. To get a sense of where Holmes lay in his coffin, they inserted a borescope, a tiny camera similar to ones used in medical procedures to map out a patient's interior. They peered into the coffin, but the images were inconclusive. So they took the chance of cracking open the coffin through the middle, figuring that route gave them the best chance of avoiding "damaging something that was really vital," Cox said. "Luckily, we hit the pelvis region."

For the next 12 hours, the crew, particularly workers from Chesco Coring & Cutting in Malvern, painstakingly chiseled concrete and pumped out water until finally they could see, resting in the coffin, the remains of H.H. Holmes, not seen since the day of his execution more than 120 years ago.

Found in the coffin excavated from a Delaware County cemetery was this engraved metal cross: “H.H. Holmes. Died May 7, 1896.”

Cox said she stuck her face into the grave to examine the skull not long after the first glimpse.

His bushy mustache was intact, but "as soon as it was exposed to air, it started to flake off," she said.

He was wearing boots, a waist coat, a suit coat. But no pants.

Why remains a mystery, but the archeologists believe Holmes may have soiled himself during his hanging.

On his chest, lay a metal cross engraved with the name H.H. Holmes.

And his brain remained intact in his skull, a "fairly common" occurrence in ancient burials, Cox said. Because brains are encased in the skull, the organ is protected from the "bacteria soup," found in the digestive tract, which does most of the work in decomposing a body, Monge said.

During the dig, rain started to fall and a section of the trench wall dropped onto Holmes' skull, the key piece for their forensic work, as if the heavens decided to spit in his face.

Cox took prompt custody of the skull before anything else fell into the coffin, she said.

It had taken the archaelogists and their team 10 days to find and exhume the notorious serial killer, but they were able to return the cemetery to normal for Mother's Day.

Now the work moved to the lab.

Part Two: Cox and Monge drill for clues to confirm their skull belongs to a serial killer.

Source/Wikimedia Commons

Source/Wikimedia Commons Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice Photo courtesy/Penn Museum

Photo courtesy/Penn Museum Photo courtesy/Penn Museum

Photo courtesy/Penn Museum Photo courtesy/Penn Museum

Photo courtesy/Penn Museum Photo courtesy/Penn Museum

Photo courtesy/Penn Museum